Neural Networks in Trading: Two-Dimensional Connection Space Models (Final Part)

Introduction

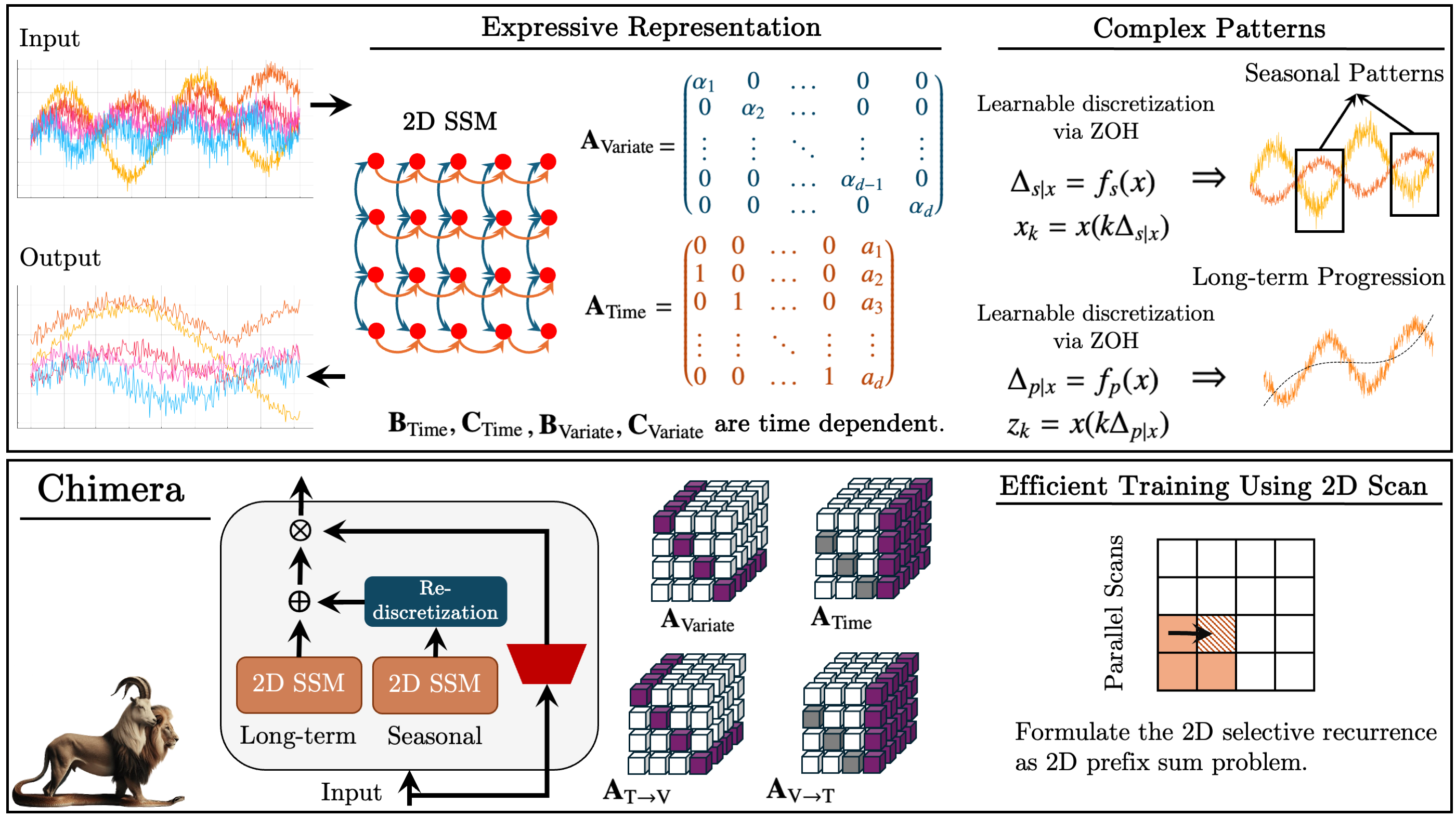

In the previous article, we became acquainted with the Chimera framework – a two-dimensional state space model (2D-SSM) based on linear transformations along the time axis and the axis of analyzed variables. It combines state space models along two axes and mechanisms for their interaction.

State space models (SSMs) are widely used in time series analysis, as they allow complex dependencies to be modeled. However, traditional SSMs account only for the temporal axis, which limits their applicability to multidimensional problems. Chimera extends this concept by incorporating the feature axis into the modeling process.

The framework operates with a discretized form of the 2D-SSM, introducing discretization steps Δ1 and Δ2. The first parameter affects temporal dependencies, while the second governs inter-variable relationships. Smaller values of Δ1 help capture long-term trends, whereas larger values emphasize seasonal variations. Similarly, discretization along the variable axis regulates the level of detail in the analysis.

To ensure correct process reconstruction, the authors of the framework introduce structural constraints on matrices A1, A2 (temporal dependencies) and A3, A4 (inter-variable relationships). The causal nature of the 2D-SSM restricts information transfer along the feature axis; therefore, Chimera uses two modules to analyze dependencies with preceding and subsequent features of the analyzed environment.

The flexibility of the Chimera framework allows the use of parameters Bi, Ci, and Δi either as data-independent constants or as functions of the input data. The use of context-dependent parameters makes the model more adaptive to the conditions of complex multidimensional systems.

The framework uses a stack of 2D-SSMs with nonlinear transformations between layers, approaching the architecture of deep models. It enables the decomposition of time series into trend and seasonal components, providing accurate pattern analysis.

Below is the authors' visualization of the Chimera framework.

In the practical part of the article, we developed an architecture to implement the authors' own vision of the proposed approaches using MQL5 and started work on their implementation. We examined changes made to the OpenCL program. We developed the structure of the 2D-SSM object and presented its initialization method. Today, we continue building algorithms for integrating the proposed approaches into our own models.

2D-SSM Object

We concluded the previous article by examining the initialization method of the CNeuron2DSSMOCL object, in which we intend to implement the functionality for constructing and training a 2D-SSM. The structure of this object is presented below.

class CNeuron2DSSMOCL : public CNeuronBaseOCL { protected: uint iWindowOut; uint iUnitsOut; CNeuronBaseOCL cHiddenStates; CLayer cProjectionX_Time; CLayer cProjectionX_Variable; CNeuronConvOCL cA; CNeuronConvOCL cB_Time; CNeuronConvOCL cB_Variable; CNeuronConvOCL cC_Time; CNeuronConvOCL cC_Variable; CNeuronConvOCL cDelta_Time; CNeuronConvOCL cDelta_Variable; //--- virtual bool feedForward(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) override; virtual bool feedForwardSSM2D(void); //--- virtual bool calcInputGradients(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) override; virtual bool calcInputGradientsSSM2D(void); virtual bool updateInputWeights(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) override; public: CNeuron2DSSMOCL(void) {}; ~CNeuron2DSSMOCL(void) {}; //--- virtual bool Init(uint numOutputs, uint myIndex, COpenCLMy *open_cl, uint window_in, uint window_out, uint units_in, uint units_out, ENUM_OPTIMIZATION optimization_type, uint batch); //--- virtual int Type(void) const { return defNeuron2DSSMOCL; } //--- virtual bool Save(int const file_handle); virtual bool Load(int const file_handle); //--- virtual bool WeightsUpdate(CNeuronBaseOCL *source, float tau); virtual void SetOpenCL(COpenCLMy *obj); //--- virtual bool Clear(void) override; };

Today, we continue this work. We will first consider the algorithm for constructing the feed-forward pass method of this object: feedForward.

bool CNeuron2DSSMOCL::feedForward(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) { CNeuronBaseOCL *inp = NeuronOCL; CNeuronBaseOCL *x_time = NULL; CNeuronBaseOCL *x_var = NULL;

In the method parameters, we receive a pointer to the input data object, which we immediately store in a local variable. Here we also declare two additional local variables to store pointers to the projection objects of the input data in the context of time and features. At this stage, we still need to form these projections.

Recall that to form these projections, we created two internal sequences in the initialization method and saved pointers to their objects in the dynamic arrays cProjectionX_Time and cProjectionX_Variable. We can now use them to obtain the required projections.

First, we generate the projection in the temporal context. We have already stored the pointer to the input data object in a local variable. Next, we create a loop that sequentially iterates over the objects of the projection model in the temporal context.

//--- Projection Time int total = cProjectionX_Time.Total(); for(int i = 0; i < total; i++) { x_time = cProjectionX_Time.At(i); if(!x_time || !x_time.FeedForward(inp)) return false; inp = x_time; }

Within the loop body, we first obtain a pointer to the next object in the sequence. We check the validity of the obtained pointer. After successfully passing this control point, we call the forward pass method of the object, passing it the pointer to the input data object.

We then store the pointer to the current object in the local variable representing the input data and proceed to the next iteration of the loop.

After completing all loop iterations, the local variable holding the projection of the input data in the temporal context will contain a pointer to the last object in the corresponding sequence. The buffer of this object will contain the projection we need.

In a similar way, we obtain the projection of the input data in the feature context.

//--- Projection Variable inp = NeuronOCL; total = cProjectionX_Variable.Total(); for(int i = 0; i < total; i++) { x_var = cProjectionX_Variable.At(i); if(!x_var || !x_var.FeedForward(inp)) return false; inp = x_var; }

To obtain the four projections of the two hidden states, it is sufficient to call a single forward pass method of the corresponding projection objects. In its parameters, we pass a pointer to the object containing the concatenated tensor of hidden states.

if(!cA.FeedForward(cHiddenStates.AsObject())) return false;

The remaining parameters of our 2D-SSM are context-dependent. Therefore, next we generate the model parameters based on the corresponding projections of the input data. For this purpose, we sequentially iterate over the model parameter generation objects and call their forward pass methods, passing pointers to the corresponding input data projection objects.

if(!cB_Time.FeedForward(x_time) || !cB_Variable.FeedForward(x_var)) return false; if(!cC_Time.FeedForward(x_time) || !cC_Variable.FeedForward(x_var)) return false; if(!cDelta_Time.FeedForward(x_time) || !cDelta_Variable.FeedForward(x_var)) return false;

At this stage, we have completed the preparation of the parameters of the two-dimensional state space model. We just need to generate new values of the hidden state and the model outputs. As you know, in the previous article these processes were moved into a separate kernel created on the OpenCL side. Now it is sufficient to call the wrapper method for this kernel. However, before doing so, it is important to note that generating a new hidden state will overwrite the current values, which we will need to perform backpropagation. Therefore, we first swap the pointers to the data buffer objects and then call the wrapper method feedForwardSSM2D.

if(!cHiddenStates.SwapOutputs()) return false; //--- return feedForwardSSM2D(); }

The next stage of our work is the construction of backpropagation algorithms for our object. Let's look at the method for error gradient distribution calcInputGradients. In the parameters of this method, we receive a pointer to the same input data object, but this time we must pass to it the error gradient corresponding to the influence of the input data on the overall result of the model.

bool CNeuron2DSSMOCL::calcInputGradients(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) { if(!NeuronOCL) return false;

Data transfer is possible only if a valid pointer to the object is available. Therefore, the first step of the algorithm is to check the received pointer, which helps prevent access to freed or uninitialized resources. This approach is critical to ensuring the stability of the computational process and preventing failures during data processing.

After successfully passing the control block, the operations for distributing the error gradient begin. This process is carried out from the level of the model's output results toward the input data, following the backpropagation mechanism, in accordance with the data flow of the feed-forward pass, but in reverse order.

We completed the forward pass method by calling the wrapper method of the kernel that generates hidden states and computes the outputs of the 2D-SSM. Accordingly, the error gradient propagation process begins by calling a similar wrapper method, but for the kernel that performs error distribution. Inside this kernel, the gradient is correctly distributed among the elements of the 2D-SSM, in accordance with their contribution to the formation of the model's output.

if(!calcInputGradientsSSM2D()) return false;

It is important to note that at this stage only the distribution of gradient values among the structural components of the model is performed. However, direct adjustment of values by the derivatives of the activation functions of the objects is not performed in this kernel. Therefore, before propagating the error gradient through the internal objects of the model, it is necessary to check if these objects contain activation functions. If required, the corresponding correction should be applied to account for the influence of nonlinear transformations on the propagated gradients. This ensures that each model parameter is updated with due consideration of its actual contribution to the formation of the output signal.

//--- Deactivation CNeuronBaseOCL *x_time = cProjectionX_Time[-1]; CNeuronBaseOCL *x_var = cProjectionX_Variable[-1]; if(!x_time || !x_var) return false; if(x_time.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(x_time.getOutput(), x_time.getGradient(), x_time.getGradient(), x_time.Activation())) return false; if(x_var.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(x_var.getOutput(), x_var.getGradient(), x_var.getGradient(), x_var.Activation())) return false; if(cB_Time.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(cB_Time.getOutput(), cB_Time.getGradient(), cB_Time.getGradient(), cB_Time.Activation())) return false; if(cB_Variable.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(cB_Variable.getOutput(), cB_Variable.getGradient(), cB_Variable.getGradient(), cB_Variable.Activation())) return false; if(cC_Time.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(cC_Time.getOutput(), cC_Time.getGradient(), cC_Time.getGradient(), cC_Time.Activation())) return false; if(cC_Variable.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(cC_Variable.getOutput(), cC_Variable.getGradient(), cC_Variable.getGradient(), cC_Variable.Activation())) return false; if(cDelta_Time.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(cDelta_Time.getOutput(), cDelta_Time.getGradient(), cDelta_Time.getGradient(), cDelta_Time.Activation())) return false; if(cDelta_Variable.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(cDelta_Variable.getOutput(), cDelta_Variable.getGradient(), cDelta_Variable.getGradient(), cDelta_Variable.Activation())) return false; if(cA.Activation() != None) if(!DeActivation(cA.getOutput(), cA.getGradient(), cA.getGradient(), cA.Activation())) return false;

Next, we proceed to the process of distributing error gradients through the internal objects of our 2D-SSM. First, we need to propagate the gradient values through the objects responsible for generating the context-dependent model parameters. Let me remind you that these parameters are formed based on the corresponding projections of the input data.

Here it is important to note that the input data projection objects already participate in the main process of forming the model's output and have received error gradient values during the preceding operations. In order to preserve the previously obtained values, we perform a swap of pointers to the corresponding data buffers.

//--- Gradient to projections X CBufferFloat *grad_x_time = x_time.getGradient(); CBufferFloat *grad_x_var = x_var.getGradient(); if(!x_time.SetGradient(x_time.getPrevOutput(), false) || !x_var.SetGradient(x_var.getPrevOutput(), false)) return false;

Next, we sequentially propagate the error gradient through the objects that form the context-dependent parameters and, at each stage, accumulate the resulting values with those that were previously stored.

//--- B -> X if(!x_time.calcHiddenGradients(cB_Time.AsObject()) || !SumAndNormilize(grad_x_time, x_time.getGradient(), grad_x_time, iWindowOut, false, 0, 0, 0, 1)) return false; if(!x_var.calcHiddenGradients(cB_Variable.AsObject()) || !SumAndNormilize(grad_x_var, x_var.getGradient(), grad_x_var, iWindowOut, false, 0, 0, 0, 1)) return false;

//--- C -> X if(!x_time.calcHiddenGradients(cC_Time.AsObject()) || !SumAndNormilize(grad_x_time, x_time.getGradient(), grad_x_time, iWindowOut, false, 0, 0, 0, 1)) return false; if(!x_var.calcHiddenGradients(cC_Variable.AsObject()) || !SumAndNormilize(grad_x_var, x_var.getGradient(), grad_x_var, iWindowOut, false, 0, 0, 0, 1)) return false;

//--- Delta -> X if(!x_time.calcHiddenGradients(cDelta_Time.AsObject()) || !SumAndNormilize(grad_x_time, x_time.getGradient(), grad_x_time, iWindowOut, false, 0, 0, 0, 1)) return false; if(!x_var.calcHiddenGradients(cDelta_Variable.AsObject()) || !SumAndNormilize(grad_x_var, x_var.getGradient(), grad_x_var, iWindowOut, false, 0, 0, 0, 1)) return false;

After the error gradients have been successfully propagated from all information flows, we restore the object pointers to their original state.

if(!x_time.SetGradient(grad_x_time, false) || !x_var.SetGradient(grad_x_var, false)) return false;

At this stage, we have obtained the error gradient values at the level of the input data projections in both contexts. Next, we need to propagate the gradients through the corresponding internal projection models. To do this, we create loops that iterate backward over the objects of the corresponding sequences.

//--- Projection Variable int total = cProjectionX_Variable.Total() - 2; for(int i = total; i >= 0; i--) { x_var = cProjectionX_Variable[i]; if(!x_var || !x_var.calcHiddenGradients(cProjectionX_Variable[i + 1])) return false; }

//--- Projection Time total = cProjectionX_Time.Total() - 2; for(int i = total; i >= 0; i--) { x_time = cProjectionX_Time[i]; if(!x_time || !x_time.calcHiddenGradients(cProjectionX_Time[i + 1])) return false; }

Note that when propagating the error gradient through the internal models of the contextual projections, we stop at the first layer of each sequence. It should be emphasized that both of our projection sequences generate their values based on the input data received as method parameters from the external program. Now we must pass the error gradient to the input data object from both internal projection models.

As is customary in such cases, we first propagate the error gradient through one information flow.

//--- Projections -> inputs if(!NeuronOCL.calcHiddenGradients(x_var.AsObject())) return false;

Then, we swap the pointers to the gradient buffer objects and propagate the errors through the second information flow.

grad_x_time = NeuronOCL.getGradient(); if(!NeuronOCL.SetGradient(x_time.getPrevOutput(), false) || !NeuronOCL.calcHiddenGradients(x_time.AsObject()) || !SumAndNormilize(grad_x_time, NeuronOCL.getGradient(), grad_x_time, 1, false, 0, 0, 0, 1) || !NeuronOCL.SetGradient(grad_x_time, false)) return false; //--- return true; }

Finally, we sum the values from both information flows and restore the data buffer pointers to their original state.

It should be noted that we do not propagate the error gradient down to the hidden state object, since this object is used only for data storage and does not contain trainable parameters.

Now that we have distributed the error gradient values among all internal objects, all that remains is to return the logical result of the performed operations to the calling program and complete the execution of the method.

With this, we conclude our examination of the algorithms used to construct the methods of the CNeuron2DSSMOCL object. The full code of this object and all its methods is provided in the attachment for further study.

The Chimera Module

The next stage of our work is the construction of the Chimera module. The authors of the framework propose using two parallel 2D-SSMs with different discretization levels and residual connections. Combining two independent state space models operating at different discretization levels enables a deeper analysis of dependencies and allows the construction of highly efficient predictive models adapted to multiscale data.

The use of 2D-SSMs with different discretization parameters makes it possible to perform a differentiated analysis of time series. The high-frequency model captures long-term patterns, while the low-frequency model focuses on identifying seasonal cycles. This separation improves forecasting accuracy, since each model adapts to its own portion of the data, minimizing information loss and errors caused by excessive aggregation of temporal features. The addition of a discretization module makes it possible to bring the outputs of the two models into a comparable form.

An additional advantage of the Chimera module is the use of residual connections, which ensure efficient information transfer between model levels. They allow gradients to be preserved and propagated during backpropagation, preventing gradient vanishing. This is especially important when training deep models, where gradient descent often encounters numerical stability issues. The model becomes more robust to information loss during data transmission between layers, and the training process becomes more stable, even when working with long time series.

We implement the proposed mechanism in the CNeuronChimera object; its structure is presented below.

class CNeuronChimera : public CNeuronBaseOCL { protected: CNeuron2DSSMOCL caSSM[2]; CNeuronConvOCL cDiscretization; CLayer cResidual; //--- virtual bool feedForward(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) override; //--- virtual bool calcInputGradients(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) override; virtual bool updateInputWeights(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) override; public: CNeuronChimera(void) {}; ~CNeuronChimera(void) {}; //--- virtual bool Init(uint numOutputs, uint myIndex, COpenCLMy *open_cl, uint window_in, uint window_out, uint units_in, uint units_out, ENUM_OPTIMIZATION optimization_type, uint batch); //--- virtual int Type(void) const { return defNeuronChimera; } //--- virtual bool Save(int const file_handle); virtual bool Load(int const file_handle); //--- virtual bool WeightsUpdate(CNeuronBaseOCL *source, float tau); virtual void SetOpenCL(COpenCLMy *obj); //--- virtual bool Clear(void) override; };

In the presented structure, we see a familiar set of overridden methods and several internal objects, whose functionality is easy to infer from their names.

All internal objects are declared statically, which allows the class constructor and destructor to remain empty. Initialization of all objects is performed in the Init method.

bool CNeuronChimera::Init(uint numOutputs, uint myIndex, COpenCLMy *open_cl, uint window_in, uint window_out, uint units_in, uint units_out, ENUM_OPTIMIZATION optimization_type, uint batch) { if(!CNeuronBaseOCL::Init(numOutputs, myIndex, open_cl, units_out * window_out, optimization_type, batch)) return false; SetActivationFunction(None);

In the method parameters, we receive a set of constants that unambiguously define the architecture of the object being created. It should be noted that the list of parameters is fully inherited from the analogous method of the previously described CNeuron2DSSMOCL object and specifies the architecture of one of the internal 2D-SSMs.

As usual, the initialization algorithm begins with a call to the method of the parent class. In this case, it is the base fully connected layer.

Next, we proceed to initialize the internal objects. As mentioned above, we use two two-dimensional state space models with different levels of detail. In the object structure, the internal models are represented as an array caSSM. To initialize the objects of this array, we organize a loop.

int index = 0; for(int i = 0; i < 2; i++) { if(!caSSM[i].Init(0, index, OpenCL, window_in, (i + 1)*window_out, units_in, units_out, optimization, iBatch)) return false; index++; }

The first state space model is initialized using the parameters received from the external program. The second model receives a feature-space dimensionality that is doubled for the output results, which allows it to capture more complex dependencies. Since both models operate on a common set of input data, the key configuration parameters remain unchanged, ensuring the integrity and consistency of the structure.

Next, we initialize the additional discretization layer, which creates a projection of the results of the second model into the subspace of the first. This is a standard convolutional layer that reduces the feature space to the specified size.

if(!cDiscretization.Init(0, index, OpenCL, 2 * window_out, 2 * window_out, window_out, units_out, 1, optimization, iBatch)) return false; cDiscretization.SetActivationFunction(None);

To prevent data loss, we disable the activation function for this object.

After initializing the information flow objects for the two state space models, we proceed to organize the residual connections. At this stage, a problem arises with summing tensors that may differ in size along one or more axes. To solve this problem, it is necessary to first project the input data into the specified result subspace. For this purpose, an internal data projection model is created, similar to the contextual projection models discussed earlier. This approach makes it possible to correctly align data dimensions, ensuring architectural stability and accurate processing of temporal dependencies.

First, we prepare a dynamic array to store pointers to the model objects and declare local variables for temporarily holding these pointers.

//--- Residual cResidual.Clear(); cResidual.SetOpenCL(OpenCL); CNeuronConvOCL *conv = NULL; CNeuronTransposeOCL *transp = NULL;

We create a data transposition object, followed by a convolutional layer that projects unit sequences into the specified time series dimensionality.

transp = new CNeuronTransposeOCL(); if(!transp || !transp.Init(0, index, OpenCL, units_in, window_in, optimization, iBatch) || !cResidual.Add(transp)) { delete transp; return false; } index++; conv = new CNeuronConvOCL(); if(!conv || !conv.Init(0, index, OpenCL, units_in, units_in, units_out, window_in, 1, optimization, iBatch) || !cResidual.Add(conv)) { delete conv; return false; } conv.SetActivationFunction(None);

This approach allows us to preserve structural dependencies within individual unit sequences of the analyzed multivariate time series.

These are followed by another block consisting of a transposition object and a convolutional layer, which perform projection of the input data along the feature axis.

index++; transp = new CNeuronTransposeOCL(); if(!transp || !transp.Init(0, index, OpenCL, window_in, units_out, optimization, iBatch) || !cResidual.Add(transp)) { delete transp; return false; } index++; conv = new CNeuronConvOCL(); if(!conv || !conv.Init(0, index, OpenCL, window_in, window_in, window_out, units_out, 1, optimization, iBatch) || !cResidual.Add(conv)) { delete conv; return false; } conv.SetActivationFunction(None);

Note that both convolutional layers do not use activation functions, which makes it possible to project the input data with minimal information loss.

At the output of the object, we plan to sum three information flows. As we usually do in such cases, we will propagate the error gradient in full along all branches. To avoid unnecessary data copy operations, we synchronize pointers to the error gradient buffers. However, it is worth noting that the convolutional layers used for data projection may include activation functions. Of course, in this particular case we did not use them and could have ignored this aspect. But in order to build a more universal solution, we do not overlook it. Therefore, the error gradient is passed to the convolutional layers only after being corrected by the derivative of the active activation function.

if(!SetGradient(caSSM[0].getGradient(), true)) return false; //--- return true; }

Finally, we return a boolean result to the calling program and complete the initialization method.

Once initialization is complete, we move on to implementing the forward-pass algorithm in the feedForward method.

bool CNeuronChimera::feedForward(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) { for(uint i = 0; i < caSSM.Size(); i++) { if(!caSSM[i].FeedForward(NeuronOCL)) return false; }

The feed-forward pass algorithm is quite simple. In the method parameters, we receive a pointer to the input data object, which we pass to the internal state space models. To do this, we organize a loop that iterates over the internal 2D-SSMs and sequentially calls their feed-forward pass methods.

After completing all loop iterations, we project the obtained results into a comparable form.

if(!cDiscretization.FeedForward(caSSM[1].AsObject())) return false;

Next, we need to obtain a projection of the input data into the result subspace. For this purpose, we organize a loop that sequentially iterates over the objects of the internal projection model, calling the feed-forward pass methods of the corresponding objects.

CNeuronBaseOCL *inp = NeuronOCL; CNeuronBaseOCL *current = NULL; for(int i = 0; i < cResidual.Total(); i++) { current = cResidual[i]; if(!current || !current.FeedForward(inp)) return false; inp = current; }

Finally, we sum the results of the three information flows, followed by data normalization.

if(!SumAndNormilize(caSSM[0].getOutput(), cDiscretization.getOutput(), Output, 1, false, 0, 0, 0, 1) || !SumAndNormilize(Output, current.getOutput(), Output, cDiscretization.GetFilters(), true, 0, 0, 0, 1)) return false; //--- return true; }

After that, we return the logical result of the performed operations to the calling program and complete the execution of the method.

However, behind the apparent simplicity of the feed-forward pass algorithm lies the use of three information flows, which introduces certain complexities in organizing the error gradient distribution process. This process is implemented within the calcInputGradients method.

bool CNeuronChimera::calcInputGradients(CNeuronBaseOCL *NeuronOCL) { if(!NeuronOCL) return false;

In the method parameters, we receive a pointer to the input data object, into which we must now pass the error gradient in accordance with its influence on the final result of the model. And in the method body, we immediately check the relevance of the received pointer. The need of such validation was discussed earlier.

Next, we correct the error gradient received from subsequent objects by the activation function of the projection layer of the second 2D-SSM and propagate it down to the level of that model.

if(!DeActivation(cDiscretization.getOutput(), cDiscretization.getGradient(), Gradient, cDiscretization.Activation())) return false; if(!caSSM[1].calcHiddenGradients(cDiscretization.AsObject())) return false;

Similarly, we adjust the error gradient by the derivative of the activation function of the last layer of the internal input data projection model and sequentially propagate it through the objects of that sequence.

CNeuronBaseOCL *residual = cResidual[-1]; if(!residual) return false; if(!DeActivation(residual.getOutput(), residual.getGradient(), Gradient, residual.Activation())) return false; for(int i = cResidual.Total() - 2; i >= 0; i--) { residual = cResidual[i]; if(!residual || !residual.calcHiddenGradients(cResidual[i + 1])) return false; }

At this stage, we reach the step of passing the error gradient to the input data level along all three branches. During gradient propagation, previously stored values are overwritten. Fortunately, we have already learned how to handle this issue. First, we propagate the error gradient from one state space model.

if(!NeuronOCL.calcHiddenGradients(caSSM[0].AsObject())) return false;

Then we swap the data buffer pointer and propagate the error gradient along the second branch, followed by summation of the data from the two information flows.

CBufferFloat *temp = NeuronOCL.getGradient(); if(!NeuronOCL.SetGradient(residual.getPrevOutput(), false) || !NeuronOCL.calcHiddenGradients(caSSM[1].AsObject()) || !SumAndNormilize(temp, NeuronOCL.getGradient(), temp, 1, false, 0, 0, 0, 1)) return false;

In the same way, we add the values of the third information flow.

if(!NeuronOCL.calcHiddenGradients((CObject*)residual) || !SumAndNormilize(temp, NeuronOCL.getGradient(), temp, 1, false, 0, 0, 0, 1) || !NeuronOCL.SetGradient(temp, false) ) return false; //--- return true; }

Only after summing the data from all information flows do we restore the object pointers to their original state.

We return the logical result of the performed operations to the calling program and complete the execution of the method.

With this, we conclude the analysis of algorithms for implementing the Chimera framework using MQL5. The full code for the presented objects and all their methods is available in the attachment.

Model Architecture

In the previous sections, we performed extensive work to implement the methods proposed by the authors of the Chimera framework using MQL5. However, the framework authors recommend using an architecture consisting of a stack of such objects with nonlinearities organized between them. The use of such an architecture contributes to the creation of a flexible and adaptive system capable of dynamically responding to changes in operating conditions. Therefore, we will briefly dwell on the architecture of the trainable models.

Let us state upfront that within the scope of this experiment, we implemented the Chimera approaches within a multitask learning framework.

The architecture of the trained models is defined in the CreateDescriptions method.

bool CreateDescriptions(CArrayObj *&actor, CArrayObj *&probability) { //--- CLayerDescription *descr; //--- if(!actor) { actor = new CArrayObj(); if(!actor) return false; } if(!probability) { probability = new CArrayObj(); if(!probability) return false; }

In the method parameters, we receive pointers to two dynamic arrays, in which we must store descriptions of the model architectures. In the body of the method, we check the relevance of the received pointers and, if necessary, create new instances of objects.

First, we describe the architecture of the Actor, which also includes the state encoder block of the environment. At the model input, we plan to feed raw, unprocessed data describing the state of the environment. These data are passed to a fully connected layer of sufficient size.

//--- Actor actor.Clear(); //--- Input layer if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronBaseOCL; int prev_count = descr.count = (HistoryBars * BarDescr); descr.activation = None; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; }

This is followed by a batch normalization layer, in which primary processing of the input data is performed and they are brought into a comparable form.

//--- layer 1 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronBatchNormOCL; descr.count = prev_count; descr.batch = 1e4; descr.activation = None; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; }

The processed data are then fed into the first Chimera module, at the output of which we expect to obtain a multidimensional temporal sequence consisting of 64 elements with 16 features in each.

//--- layer 2 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronChimera; //--- Window { int temp[] = {BarDescr, 16}; //In, Out if(ArrayCopy(descr.windows, temp) < int(temp.Size())) return false; } //--- Units { int temp[] = {HistoryBars, 64}; //In, Out if(ArrayCopy(descr.units, temp) < int(temp.Size())) return false; } descr.batch = 1e4; descr.activation = None; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; }

This is followed by a convolutional layer with a SoftPlus activation function to introduce nonlinearity.

//--- layer 3 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronConvOCL; descr.count = 64; descr.window = 16; descr.step = 16; descr.window_out = 16; descr.activation = SoftPlus; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; }

In a similar manner, we add two more Chimera modules, inserting nonlinearities between them.

//--- layer 4 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronChimera; //--- Window { int temp[] = {16, 32}; //In, Out if(ArrayCopy(descr.windows, temp) < int(temp.Size())) return false; } //--- Units { int temp[] = {64, 32}; //In, Out if(ArrayCopy(descr.units, temp) < int(temp.Size())) return false; } descr.batch = 1e4; descr.activation = None; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; } //--- layer 5 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronConvOCL; descr.count = 32; descr.window = 32; descr.step = 32; descr.window_out = 16; descr.activation = SoftPlus; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; } //--- layer 6 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronChimera; //--- Window { int temp[] = {16, 32}; //In, Out if(ArrayCopy(descr.windows, temp) < int(temp.Size())) return false; } //--- Units { int temp[] = {32, 16}; //In, Out if(ArrayCopy(descr.units, temp) < int(temp.Size())) return false; } descr.batch = 1e4; descr.activation = None; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; }

At the same time, by analogy with the ResNeXt framework, we reduce the sequence length and proportionally increase the feature space dimensionality.

Next comes the decision-making head, consisting of three consecutive fully connected layers.

//--- layer 7 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronBaseOCL; descr.count = 512; descr.batch = 1e4; descr.activation = TANH; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; } //--- layer 8 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronBaseOCL; descr.count = 256; descr.activation = TANH; descr.batch = 1e4; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; } //--- layer 9 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronBaseOCL; prev_count = descr.count = NActions; descr.activation = SoftPlus; descr.batch = 1e4; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; }

The results of their operation are normalized using a batch normalization layer.

//--- layer 10 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronBatchNormOCL; descr.count = prev_count; descr.batch = 1e4; descr.activation = None; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; }

As in the previously discussed models, a risk management module is added at the output of the Actor.

//--- layer 11 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronMacroHFTvsRiskManager; //--- Windows { int temp[] = {3, 15, NActions, AccountDescr}; //Window, Stack Size, N Actions, Account Description if(ArrayCopy(descr.windows, temp) < int(temp.Size())) return false; } descr.count = 10; descr.window_out = 16; descr.step = 4; // Heads descr.batch = 1e4; descr.activation = None; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; } //--- layer 12 if(!(descr = new CLayerDescription())) return false; descr.type = defNeuronConvOCL; descr.count = NActions / 3; descr.window = 3; descr.step = 3; descr.window_out = 3; descr.activation = SIGMOID; descr.optimization = ADAM; if(!actor.Add(descr)) { delete descr; return false; }

The model for estimating the probability of the direction of the upcoming price movement was transferred from the previous article almost unchanged. Only minor adjustments were made to the activation functions used in the hidden layers. Therefore, we will not examine it in detail here. A full description of the model architectures can be found in the attachment. The complete code for training and testing the models is also provided there and was transferred from the previous work without changes.

Testing

After completing the implementation of our own interpretation of the approaches proposed by the authors of the Chimera framework, we proceed to the final stage of our work - training and testing the models on real historical data.

To train the models, we used a training dataset collected during the training of the previously discussed models. This training dataset was built using historical data of the EURUSD currency pair for the entire year 2024 on the M1 timeframe. All indicator parameters were set to their default values. A detailed description of the training dataset preparation process can be found at this link.

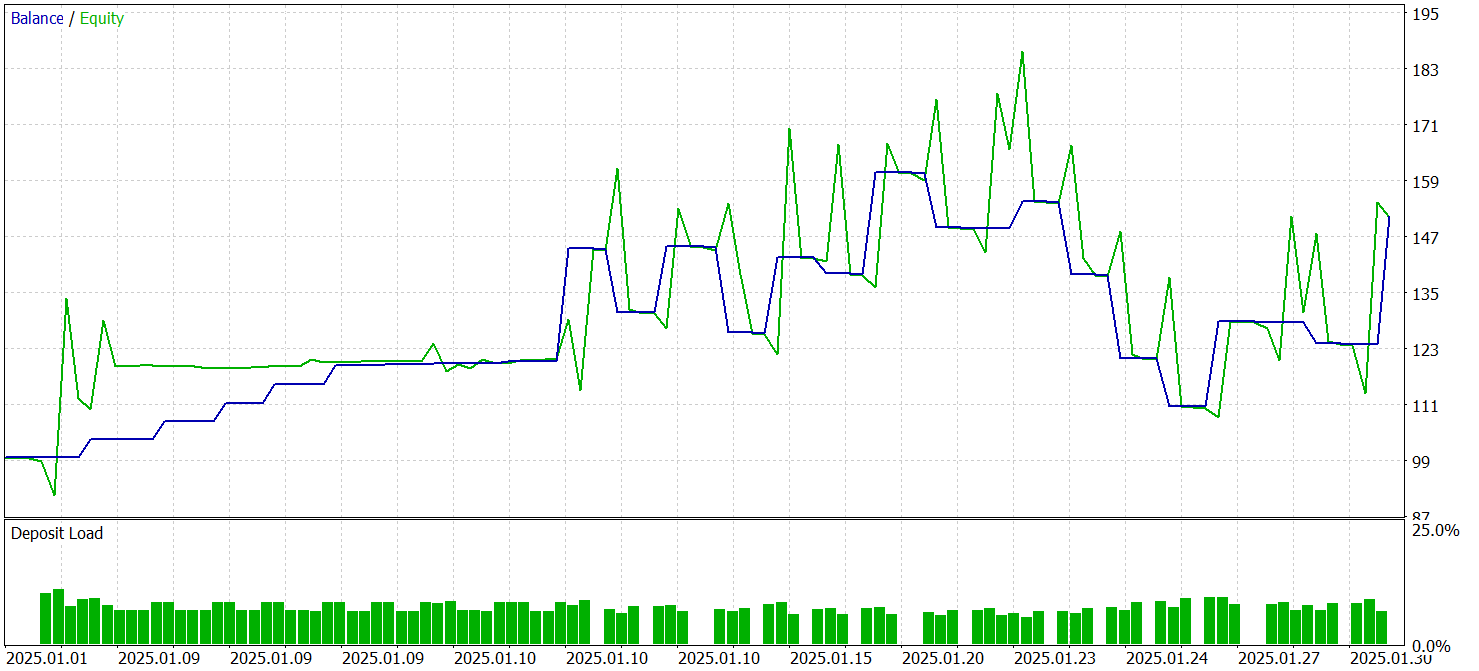

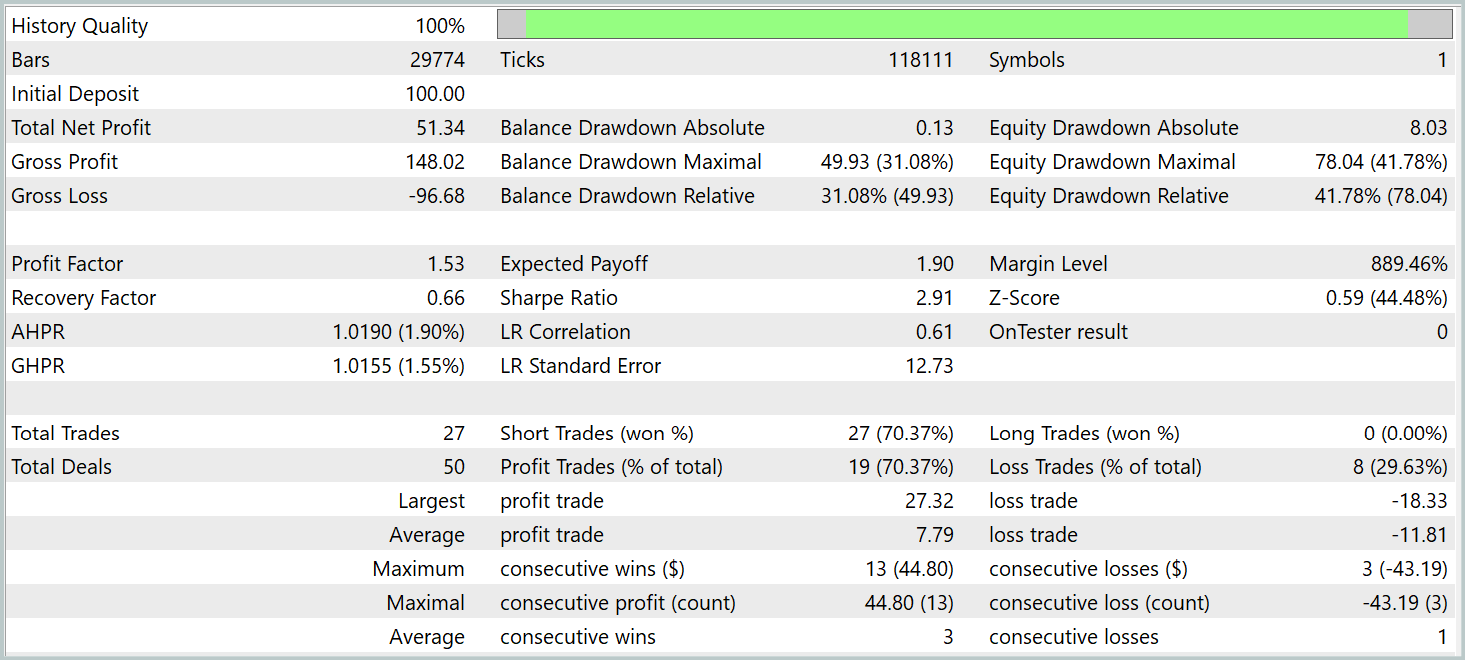

Testing of the trained models was carried out in the MetaTrader 5 Strategy Tester on historical data from January 2025, while keeping the other training parameters unchanged. The testing results are presented below.

According to the test results, the model was able to generate a profit. More than 70% of the trades were closed with a profit. The profit factor was recorded at 1.53.

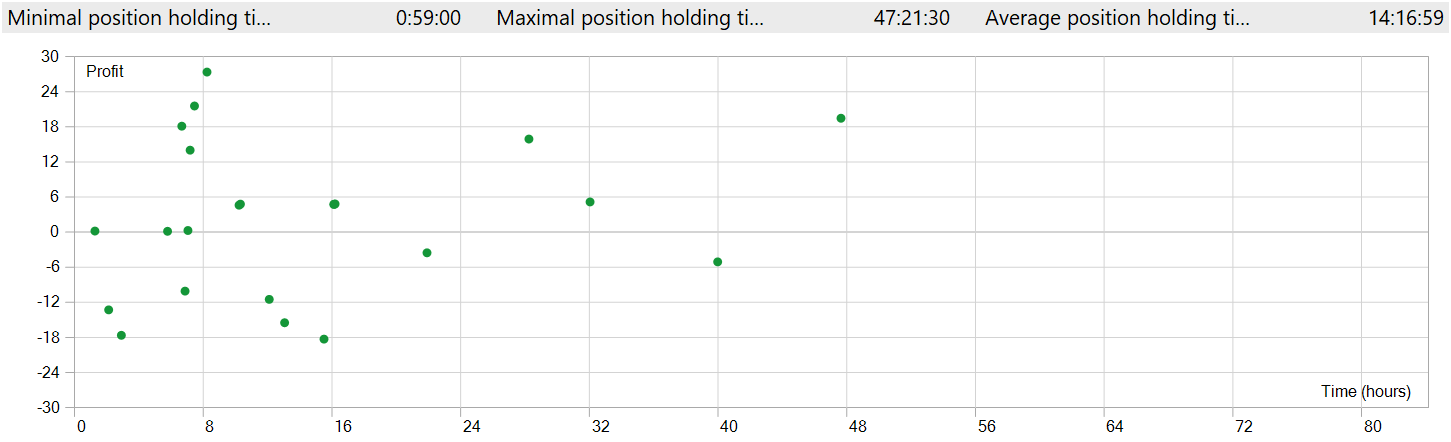

However, several points should be noted. The models were tested on the M1 timeframe. At the same time, the model executed only 27 trades, which is quite low for high-frequency trading on the minimal timeframe. Moreover, the model opened only short positions, which also raises questions.

The position holding time also raises concerns. The fastest position, so to speak, was closed almost an hour after opening. The average holding time exceeds 14 hours. And this is while testing the model on the M1 timeframe.

To display position opening and closing on a single chart window, it was necessary to increase the timeframe. In this form, we clearly observe trading in the direction of the global trend. This, of course, does not align with the notion of high-frequency trading on the M1 timeframe. However, it is evident that the implemented model is capable of capturing long-term trends while ignoring short-term fluctuations.

Conclusion

In the last two articles, we considered the Chimera framework, which is based on a two-dimensional state space model. This approach introduces innovative techniques for modeling multivariate time series, making it possible to account for complex relationships both in the temporal context and in the feature space.

In the practical part of our work, we implemented our interpretation of the framework approaches in MQL5. The constructed model was trained and tested on real historical data. The test results turned out to be somewhat unexpected. During the testing period, the model was able to generate a profit. However, contrary to expectations, we observed trading in the direction of the global trend with long position holding times, even though the model was tested on the M1 timeframe.

References

- Chimera: Effectively Modeling Multivariate Time Series with 2-Dimensional State Space Models

- Other articles from this series

Programs used in the article

| # | Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Research.mq5 | Expert Advisor | Expert Advisor for collecting samples |

| 2 | ResearchRealORL.mq5 | Expert Advisor | Expert Advisor for collecting samples using the Real-ORL method |

| 3 | Study.mq5 | Expert Advisor | Model training Expert Advisor |

| 4 | Test.mq5 | Expert Advisor | Model testing Expert Advisor |

| 5 | Trajectory.mqh | Class library | System state and model architecture description structure |

| 6 | NeuroNet.mqh | Class library | A library of classes for creating a neural network |

| 7 | NeuroNet.cl | Code Base | OpenCL program code |

Translated from Russian by MetaQuotes Ltd.

Original article: https://www.mql5.com/ru/articles/17241

Warning: All rights to these materials are reserved by MetaQuotes Ltd. Copying or reprinting of these materials in whole or in part is prohibited.

This article was written by a user of the site and reflects their personal views. MetaQuotes Ltd is not responsible for the accuracy of the information presented, nor for any consequences resulting from the use of the solutions, strategies or recommendations described.

Market Simulation (Part 09): Sockets (III)

Market Simulation (Part 09): Sockets (III)

Reimagining Classic Strategies (Part 21): Bollinger Bands And RSI Ensemble Strategy Discovery

Reimagining Classic Strategies (Part 21): Bollinger Bands And RSI Ensemble Strategy Discovery

Introduction to MQL5 (Part 35): Mastering API and WebRequest Function in MQL5 (IX)

Introduction to MQL5 (Part 35): Mastering API and WebRequest Function in MQL5 (IX)

MQL5 Trading Tools (Part 11): Correlation Matrix Dashboard (Pearson, Spearman, Kendall) with Heatmap and Standard Modes

MQL5 Trading Tools (Part 11): Correlation Matrix Dashboard (Pearson, Spearman, Kendall) with Heatmap and Standard Modes

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use