From Basic to Intermediate: Template and Typename (V)

Introduction

In the previous article, From Basic to Intermediate: Template and Typename (IV), I explained (as clearly and simply as possible) how we can create a template in order to generalize a type of modeling, effectively creating what can be considered a data type overload. However, at the end of that article, I introduced something that, for many readers, might have been quite difficult to grasp: the transfer of data into a function or procedure that is itself implemented as a template. Because that concept requires a more detailed explanation, I decided to dedicate this article to that topic. Moreover, there's another concept closely related to it: one that can make the difference between being able or unable to implement a given solution using templates.

So, to begin this article properly, let's start a new topic to explain why the last piece of code from the previous article actually works.

Expanding the Mind

In the last article, we implemented something that looked rather unusual. I suspect that many of you had never seen anything quite like it. To properly explain what it all means, we need to review the code that was used. You can see it below.

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. union un_01 06. { 07. T value; 08. uchar u8_bits[sizeof(T)]; 09. }; 10. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 11. void OnStart(void) 12. { 13. { 14. un_01 <ulong> info; 15. 16. info.value = 0xA1B2C3D4E5F6789A; 17. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(info)); 18. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", info.value); 19. Swap(info); 20. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", info.value); 21. } 22. 23. { 24. un_01 <ushort> info; 25. 26. info.value = 0xCADA; 27. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(info)); 28. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", info.value); 29. Swap(info); 30. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", info.value); 31. } 32. } 33. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 34. template <typename T> 35. void Swap(un_01 <T> &arg) 36. { 37. for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 38. { 39. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 40. arg.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 41. arg.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 42. } 43. } 44. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 01

Now, considering that you have probably experimented quite a bit with the code from the previous article, this Code 01 must have caught your attention. Particularly the way the procedure on line 35 is declared. To understand what and, more importantly, why things are declared that way in Code 01, we need to take a closer look.

First, we need to understand that the procedure on line 35 is one that the compiler will overload during the process of generating the executable code. As mentioned in the previous article, I posed a challenge to create code that performs the same task as Code 01, but using template-based overloading for the procedure implemented on line 35. The goal of this exercise is to clarify why the procedure needs to be declared in that particular way.

In theory, this exercise seems simple, but in practice, it can be somewhat tricky. So let's work through it together. This way, you'll understand why the declaration must be written the way it is in Code 01.

We won't modify the entire code, but only the procedure, Thus we can focus on the fragment shown below.

. . . 33. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 34. void Swap(un_01 <ulong> &arg) 35. { 36. for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 37. { 38. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 39. arg.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 40. arg.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 41. } 42. } 43. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 44. void Swap(un_01 <ushort> &arg) 45. { 46. for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 47. { 48. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 49. arg.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 50. arg.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 51. } 52. } 53. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Fragment 01

This Fragment 01 replaces the procedure found on line 35. But pay close attention: what Fragment 01 contains is exactly what the compiler generates when it translates and overloads the procedure seen in Code 01. However, in this case, only the ulong and ushort types are covered, unlike Code 01, which covers all primitive types.

So, why do we need to declare things the way they appear in Fragment 01? I believe the reason should now be much clearer. If you understood the explanation in the previous article, you probably see why lines 14 and 24 in Code 01 must be declared in that specific way. And for the same reason, lines 34 and 44 in Fragment 01 also need to follow a similar structure.

Remember something we discussed back in the early articles about passing by value or by reference: when we declare a variable, we must specify both its type and its name. And within a function or procedure declaration, we are indeed declaring a variable that may or may not be constant, depending on the case.

Alright, so as far as variable declaration inside a procedure goes, things seem relatively simple. But there's still a question: Earlier, when we talked about special variables, we mentioned that a function could be one of those. In the situation we're dealing with now, how could we use a function to implement what we need?

That's an excellent question, dear reader. Indeed, when we want to return values, we need to use a different kind of declaration than the one we use for procedures. However, the underlying concept remains very similar to what we've seen so far. Remember: when we return something, that return value is itself a type of variable, as if we were declaring a variable whose name is the name of the function. With that in mind, we can extend the same basic concept and implement our code properly.

Before we move on to the generalized form, let's look at an approach similar to Fragment 01. However, since functions behave differently from procedures, we'll also make some changes to Code 01. The result is shown below.

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. union un_01 06. { 07. T value; 08. uchar u8_bits[sizeof(T)]; 09. }; 10. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 11. void OnStart(void) 12. { 13. { 14. un_01 <ulong> info; 15. 16. info.value = 0xA1B2C3D4E5F6789A; 17. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(info)); 18. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", info.value); 19. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", Swap(info).value); 20. } 21. 22. { 23. un_01 <ushort> info; 24. 25. info.value = 0xCADA; 26. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(info)); 27. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", info.value); 28. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", Swap(info).value); 29. } 30. } 31. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 32. un_01 <ulong> Swap(const un_01 <ulong> &arg) 33. { 34. un_01 <ulong> local; 35. 36. for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 37. { 38. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 39. local.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 40. local.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 41. } 42. 43. return local; 44. } 45. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 46. un_01 <ushort> Swap(const un_01 <ushort> &arg) 47. { 48. un_01 <ushort> local; 49. 50. for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 51. { 52. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 53. local.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 54. local.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 55. } 56. 57. return local; 58. } 59. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 02

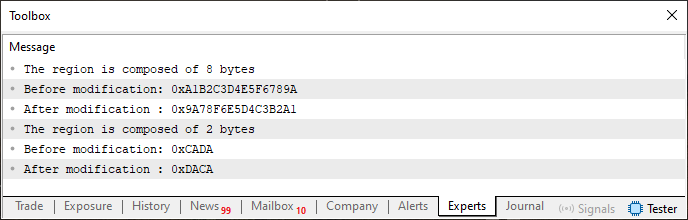

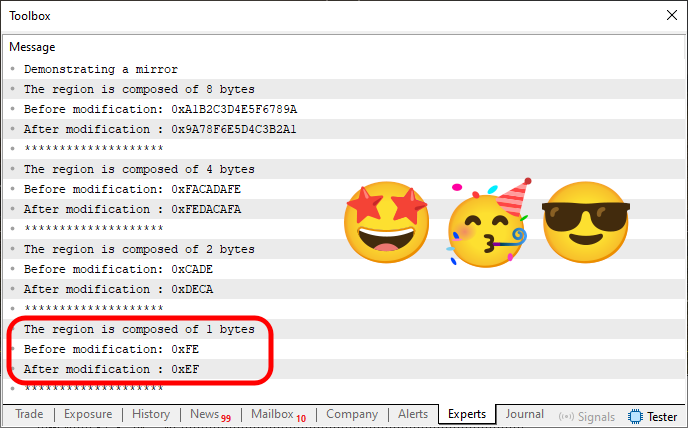

Notice that this Code 02 is slightly different from Code 01. But despite those differences, it still produces the same result. That is, when you compile Code 02 and run it in the MetaTrader 5 terminal, you'll get the output shown below.

Figure 01

As you can see, the result is exactly the same as what you get when running Code 01, even after replacing its procedure with Fragment 01. However, Fragment 01 restricts the data types that the compiler can use when working with the union un_01.

This Code 02 has the same limitation. Now, I want you to notice how Fragment 01 was rewritten so that we could use functions instead of procedures. Pay attention to lines 19 and 28 in Code 02, where we use what's known as a special variable called 'Swap', which is actually a function, but one designed to be used as a read-only variable.

Pretty cool, isn't it? Just like Fragment 01 shows what the procedure in Code 01 would do, we can also transform the functions in Code 02 into a template. This way, the code would have the same behavior and flexibility in choosing types as Code 01. To do this, we simply need to generalize the common parts of the functions in Code 02. The compiler then can dynamically substitute the data type whenever needed. Once you understand this concept, you can rewrite Code 02 into Code 03, as shown next.

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. union un_01 06. { 07. T value; 08. uchar u8_bits[sizeof(T)]; 09. }; 10. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 11. void OnStart(void) 12. { 13. { 14. un_01 <ulong> info; 15. 16. info.value = 0xA1B2C3D4E5F6789A; 17. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(info)); 18. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", info.value); 19. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", Swap(info).value); 20. } 21. 22. { 23. un_01 <ushort> info; 24. 25. info.value = 0xCADA; 26. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(info)); 27. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", info.value); 28. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", Swap(info).value); 29. } 30. } 31. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 32. template <typename T> 33. un_01 <T> Swap(const un_01 <T> &arg) 34. { 35. un_01 <T> local; 36. 37. for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 38. { 39. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 40. local.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 41. local.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 42. } 43. 44. return local; 45. } 46. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 03

This Code 03 represents an improvement over Code 02, since we now have the ability to use any data type we want. The compiler is able to interpret this correctly and automatically generate all the necessary overloads for our application to function successfully.

With that, what once seemed extremely complex and difficult to understand has become simple and straightforward. Any beginner can now use templates with ease. Notice how things that initially appear complicated often become easy once we truly understand the underlying concepts? That's why I keep insisting that you practice what's being shown. Not to memorize ways to write code, but to understand how the concepts are being applied in each specific context.

Now, this is the part many would classify as intermediate or even advanced. However, in my view, what we've covered so far is still just the basics. We still need to discuss something important that we've been using all along but haven't explicitly addressed yet: the reserved word 'typename'.

To explain this properly, we'll need to start a new topic so we can study it calmly and clearly. Let's do that now.

Typename: What Is It Really For?

A very reasonable and important question to ask is: What exactly is typename? And what is its real purpose in a practical program? Well, dear reader, understanding this can help you implement some quite interesting types of code. Generally speaking, however, typename is used for very specific purposes that is often related to testing or type inspection.

At least as far as I know, typename is rarely used for anything other than ensuring that a function or procedure overloaded by the compiler doesn't behave unpredictably. It's not uncommon, when we implement something as a template, to encounter inconsistent or incoherent results during use - often because a certain type wasn't correctly handled by the template.

In other cases, we might want a function or procedure overloaded by the compiler to behave differently depending on the type of data being used. The same function could act one way for one type and another way for a different type. This may sound confusing, but in practice, it can sometimes be necessary. Understanding how typename works will help you handle such situations confidently.

To demonstrate this, let's try to create an example that's at least a bit fun. Because working with typename can be a rather dry and technical subject. We'll try to make it more engaging. Let's use the code below.

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. union un_01 06. { 07. T value; 08. uchar u8_bits[sizeof(T)]; 09. }; 10. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 11. void OnStart(void) 12. { 13. Print("Demonstrating a mirror"); 14. 15. Check((ulong)0xA1B2C3D4E5F6789A); 16. Check((uint)0xFACADAFE); 17. Check((ushort)0xCADE); 18. Check((uchar)0xFE); 19. } 20. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 21. template <typename T> 22. void Check(const T arg) 23. { 24. un_01 <T> local; 25. string sz; 26. 27. local.value = arg; 28. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(local)); 29. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", local.value); 30. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", Mirror(local).value); 31. StringInit(sz, 20, '*'); 32. Print(sz); 33. } 34. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 35. template <typename T> 36. un_01 <T> Mirror(const un_01 <T> &arg) 37. { 38. un_01 <T> local; 39. 40. for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 41. { 42. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 43. local.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 44. local.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 45. } 46. 47. return local; 48. } 49. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 04

In this Code 04, we're playing around with everything we've discussed so far. Our goal is to understand how typename can be used in a real program. The objective is to mirror (or "reflect") the information stored in memory (or, in this case, in a variable) so that the right half swaps places with the left half. Simple enough.

When you look at Code 04, you can see that it's essentially a slight variation of the examples we've been working with. That's intentional, as it allows us to focus on what's new and important to understand.

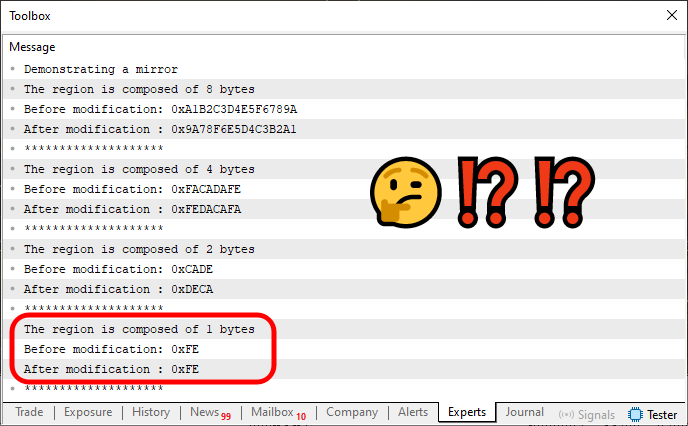

When this Code 04 is executed in MetaTrader 5, we get the result shown below.

Figure 02

Notice that one of the values is highlighted. The reason is simple: IT'S NOT MIRRORED. The right side is NOT being swapped with the left. However, for all other values, the mirroring works perfectly. The issue arises because when we use a data type that occupies only one byte, we lose the ability to mirror one side with the other.

In MQL5, we know that there are only two types that fit this one-byte criterion: uchar (for unsigned values) and char (for signed values). However, implementing separate overloaded calls to handle these types individually would be somewhat inconvenient, since it would break the uniformity of our operation. The ideal solution is to continue using the Mirror function implemented on line 36 to handle this behavior.

But now comes the key question: How can we tell the compiler how to handle the uchar or char types in order to perform the mirroring operation?

Well, dear reader, there are many ways to do this. One practical and straightforward approach would be to read the bits one by one and swap them — right for left and left for right. This would eliminate the need to overload functions or procedures. However, that's not our goal. Consider that a homework challenge: try to implement a solution that mirrors data bit by bit, swapping the bits of the input information. It's an excellent exercise to solidify these concepts and to start thinking like a true programmer.

But as for our case right now: how do we solve this issue? Well, here's where things get really interesting. You see, typename can literally tell us the name of the data type being received. In other words, we can ask typename what the type of a given variable or parameter is. To make this concept more tangible and easier to grasp, let's make a small modification to Code 04. You can see the updated version in the code below.

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. union un_01 06. { 07. T value; 08. uchar u8_bits[sizeof(T)]; 09. }; 10. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 11. void OnStart(void) 12. { 13. Print("Demonstrating a mirror"); 14. 15. Check((ulong)0xA1B2C3D4E5F6789A); 16. Check((uint)0xFACADAFE); 17. Check((ushort)0xCADE); 18. Check((uchar)0xFE); 19. } 20. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 21. template <typename T> 22. void Check(const T arg) 23. { 24. un_01 <T> local; 25. string sz; 26. 27. local.value = arg; 28. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(local)); 29. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", local.value); 30. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", Mirror(local).value); 31. StringInit(sz, 20, '*'); 32. Print(sz); 33. } 34. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 35. template <typename T> 36. un_01 <T> Mirror(const un_01 <T> &arg) 37. { 38. un_01 <T> local; 39. 40. PrintFormat("Type is: [%s] or variable route is: {%s}", typename(T), typename(arg)); 41. for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 42. { 43. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 44. local.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 45. local.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 46. } 47. 48. return local; 49. } 50. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 05

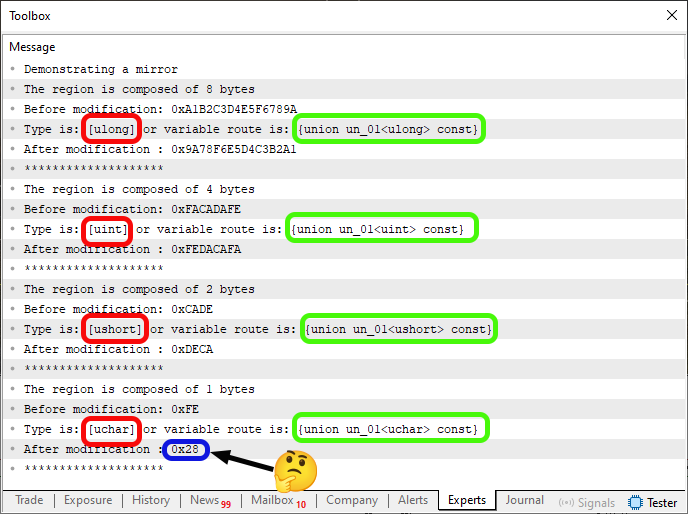

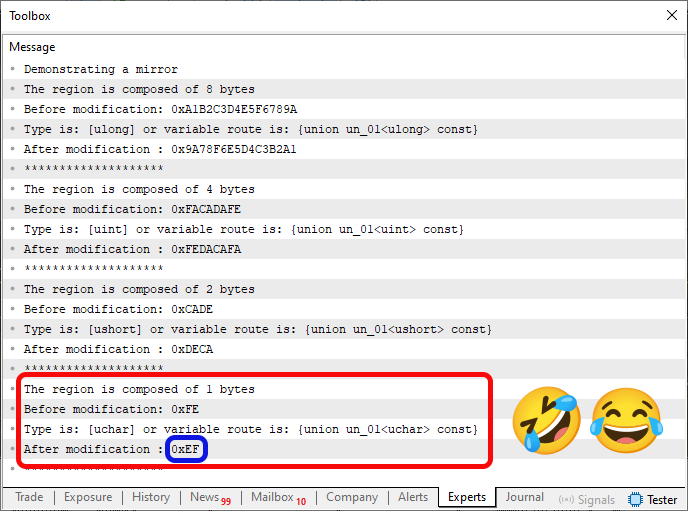

When you run this Code 05, you'll see something very similar to the image shown below.

Figure 03

Now, in this Figure 03, something appeared that I simply couldn't make sense of. There's no sense in this appearance. That's why it's highlighted in blue. Truly bizarre. But that's not the point. What really matters are the areas highlighted in red and green. So, where did that information come from? Well, those outputs were printed because of line 40 in Code 05. Now pay close attention — this is extremely important to understand clearly. Otherwise, you might run into problems later when trying to use the information highlighted in red and green in Figure 03.

ALL THE RED HIGHLIGHTS refer to the fact that we asked the compiler to tell us the PRIMITIVE DATA TYPE being used by the function. The GREEN HIGHLIGHTS, on the other hand, correspond to the compiler's response to our request for the DATA TYPE ACTUALLY USED BY THE VARIABLE. There's a subtle difference between the two questions. But the answers can be completely different.

Normally, and quite often, you'll see many programmers asking the compiler to reveal the type of a variable. However, this doesn't always give us the right answer, or at least not the one we expect. That's because we may be in a situation similar to the one shown above, where the primitive data type is one thing, but the variable data type is more complex, even though it's somehow derived from that primitive type.

But don't worry about how to check this just yet. These codes are attached below so you can study and experiment with them. Returning to our main point — what interests us is the information highlighted in red in Figure 03. Notice that all of them are written exactly as they were declared during the code implementation phase. However, I want to draw your attention to something very important: these values are strings. This means we can compare them to other strings during runtime. And that's what matters here.

Now we have a foundation to work from. We just need to perform a small test to isolate the uchar or char types (the single-byte types) in order to mirror the values properly. To do this, we'll make a small modification. This time we return to the original Code 04 to produce the necessary adjustment. You can see the modified version below.

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. union un_01 06. { 07. T value; 08. uchar u8_bits[sizeof(T)]; 09. }; 10. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 11. void OnStart(void) 12. { 13. Print("Demonstrating a mirror"); 14. 15. Check((ulong)0xA1B2C3D4E5F6789A); 16. Check((uint)0xFACADAFE); 17. Check((ushort)0xCADE); 18. Check((uchar)0xFE); 19. } 20. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 21. template <typename T> 22. void Check(const T arg) 23. { 24. un_01 <T> local; 25. string sz; 26. 27. local.value = arg; 28. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(local)); 29. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", local.value); 30. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", Mirror(local).value); 31. StringInit(sz, 20, '*'); 32. Print(sz); 33. } 34. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 35. template <typename T> 36. un_01 <T> Mirror(const un_01 <T> &arg) 37. { 38. un_01 <T> local; 39. 40. if (StringFind(typename(T), "char") > 0) local.value = (arg.value << 4) | (arg.value >> 4); 41. else for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 42. { 43. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 44. local.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 45. local.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 46. } 47. 48. return local; 49. } 50. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 06

Now pay close attention, dear reader. What I'm doing here can be achieved in many different ways. Each with its own pros and cons, some are easier to understand than others. So if you don't fully grasp what's happening in this Code 06, don't worry. It is provided in the attachment, so you can modify and experiment with it until it all makes sense.

Before doing that, though, it's important to first understand what I've implemented and what the final result will be when you run this code. Otherwise, you might change something and get a result different from the expected one, mistakenly thinking everything is working fine.

So let's move on. First, let's look at the result when we run the program in the MetaTrader 5 terminal. You can see it below.

Figure 04

Simply wonderful. The code successfully achieved its goal, which is to mirror the value of each variable so that the right half swaps with the left, exactly as expected. But notice that, compared to Code 04, the only addition in Code 06 is line 40 (plus a small adjustment in line 41). That's not the part I want to emphasize, though. What I really want you to notice is the function I used to test which method we should use for mirroring.

This StringFind function from the MQL5 standard library allows us to search for a specific substring within the string returned by typename. This is very important, because REGARDLESS of whether we're using the variable's declared type or the compiler's primitive type, the searched fragment might appear in either. And here's the key reason why I'm using this function in particular: StringFind will successfully detect both "uchar" and "char". The only difference between the two is the letter "u" at the beginning of "uchar". So, either way, the test will be performed and a result will be returned.

That said, each case is unique. Depending on what you're trying to build in your code, this small difference between type names, even though they have the same byte size, can affect the final result. That's because in one case we might have negative values, while in the other we won't. Of course, we can explicitly apply type casting to correct this if needed. Still, it's worth paying attention whenever you rely on type information generated by the compiler.

Now the fun part begins. As you may have noticed, the result in Figure 04 is correct, everything works perfectly. But we still need to take into account the strange result seen in Figure 03. I have no idea why the compiler decided to play a "little prank" on us. If we modify Code 06 so that it displays the same type information that Code 05 was printing, everything works fine. However, something BIZARRE happened when compiling Code 05, producing that strange output seen in Figure 03.

To prove this, the modified code is shown below.

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. union un_01 06. { 07. T value; 08. uchar u8_bits[sizeof(T)]; 09. }; 10. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 11. void OnStart(void) 12. { 13. Print("Demonstrating a mirror"); 14. 15. Check((ulong)0xA1B2C3D4E5F6789A); 16. Check((uint)0xFACADAFE); 17. Check((ushort)0xCADE); 18. Check((uchar)0xFE); 19. } 20. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 21. template <typename T> 22. void Check(const T arg) 23. { 24. un_01 <T> local; 25. string sz; 26. 27. local.value = arg; 28. PrintFormat("The region is composed of %d bytes", sizeof(local)); 29. PrintFormat("Before modification: 0x%I64X", local.value); 30. PrintFormat("After modification : 0x%I64X", Mirror(local).value); 31. StringInit(sz, 20, '*'); 32. Print(sz); 33. } 34. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 35. template <typename T> 36. un_01 <T> Mirror(const un_01 <T> &arg) 37. { 38. un_01 <T> local; 39. 40. PrintFormat("Type is: [%s] or variable route is: {%s}", typename(T), typename(arg)); 41. if (StringFind(typename(T), "char") > 0) local.value = (arg.value << 4) | (arg.value >> 4); 42. else for (uchar i = 0, j = sizeof(arg) - 1, tmp; i < j; i++, j--) 43. { 44. tmp = arg.u8_bits[i]; 45. local.u8_bits[i] = arg.u8_bits[j]; 46. local.u8_bits[j] = tmp; 47. } 48. 49. return local; 50. } 51. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 07

Note that Code 07 is a combination of Code 05 and Code 06. When we run it, we get the following output:

Figure 05

Isn't that funny? Who knows what really happened during compilation or execution of Code 05? Thankfully, we're dealing with examples where a little quirk or inconsistency doesn't matter much. Still, it's amusing to see these odd compiler surprises.

Final Thoughts

In this article, we wrapped up the explanations and exercises designed to help you truly understand what function and procedure overloading are. The goal was to show how the same function or procedure name can be reused with different data types.

We began this journey with simple examples, like those in From Basic to Intermediate: Overloading, and gradually moved toward more elaborate cases, building templates for functions and procedures. Since these concepts extend beyond just functions and procedures, we began using templates as a way to reduce coding effort. Using templates, we effectively delegate the generation of overloaded versions to the compiler, making our lives as programmers much easier.

However, the concept of templates can be expanded even further, for example, to create and manage more complex data types. In this series, we focused specifically on unions, keeping our examples within that modeling framework. This allowed us to experiment with type overloading. This, in turn, opened the door to doing more with less code. The compiler took on the responsibility of maintaining consistency and correctness. Our job was simply to tell it which primitive type to use.

However, we can go even further - introducing ways to control behavior depending on which primitive type is used in our code. To achieve that, we use typename, which lets us identify the exact type being handled, whether determined by the compiler or by the variable itself.

I know that for many of you, especially beginners, all of this might seem complicated or confusing. But remember, we're still at the most basic and accessible level of programming concepts. So my advice, dear reader, is to study and practice everything we've covered here. Pay close attention to each concept explained in these articles so far, because from here on out, things will only get more challenging and more interesting. And for those of you who truly love programming - we're about to enter a brand-new playground called MQL5.

See you in the next article, where we'll begin exploring an even more fascinating and enjoyable topic.

Translated from Portuguese by MetaQuotes Ltd.

Original article: https://www.mql5.com/pt/articles/15671

Warning: All rights to these materials are reserved by MetaQuotes Ltd. Copying or reprinting of these materials in whole or in part is prohibited.

This article was written by a user of the site and reflects their personal views. MetaQuotes Ltd is not responsible for the accuracy of the information presented, nor for any consequences resulting from the use of the solutions, strategies or recommendations described.

From Novice to Expert: Parameter Control Utility

From Novice to Expert: Parameter Control Utility

Overcoming The Limitation of Machine Learning (Part 6): Effective Memory Cross Validation

Overcoming The Limitation of Machine Learning (Part 6): Effective Memory Cross Validation

Introduction to MQL5 (Part 26): Building an EA Using Support and Resistance Zones

Introduction to MQL5 (Part 26): Building an EA Using Support and Resistance Zones

Neural Networks in Trading: A Multimodal, Tool-Augmented Agent for Financial Markets (Final Part)

Neural Networks in Trading: A Multimodal, Tool-Augmented Agent for Financial Markets (Final Part)

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use