From Basic to Intermediate: Struct (V)

Introduction

In the previous article, "From Basic to Intermediate: Struct (IV)", we began discussing programming for creating structured code more seriously and in a more applied manner. To many, such points might seem silly and lacking practical sense, especially since the focus nowadays is almost entirely on object-oriented programming. And many do not realize that OOP did not appear overnight. It is the result of extensive research and debates within the entire programming community, emerging only when the limitations of structural programming became apparent.

However, unlike conventional programming where we declare variables, functions, and procedures to solve a specific task, structural programming aims to implement an approach where we can solve not just one task, but a whole range of interconnected problems.

I know many of you (especially beginners) are probably thinking: «Friend, I don't want to learn this. I want to learn how to create an Expert Advisor or an indicator. Learning to implement solutions I'm not even planning to use is just not for me». Alright, you have the right to think that way. But if you don't understand how to implement solutions that have nothing to do with an indicator or even a piece of EA code, you will hit a dead end sooner than you think. This happens because you don't understand how to implement solutions that are neither obvious nor simple.

To be able to solve any problems that arise, you need to have a programmer's mindset. And one of these problems is precisely what hasn't been explained so far: how to extend structural programming to solve broader tasks. In other words, if we create code to solve a problem with integer types, how can we implement a solution for floating-point data without redoing everything from scratch? This is a very interesting question, but it can also be very confusing, as there are different ways to achieve the same thing.

I will try to explain at least two different ways to do this. The second method involves memory manipulation, and I don't know if you're ready for that. However, let's start with the simplest one. This will give you a general idea of how to approach the problem. So, it's time to focus on what this article is about. Now it's going to get interesting.

How to use templates in structures

Here we will analyze the first method of using templates in data structures, which is the simplest way to understand how structures are overloaded. Remember, everything shown here is for educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should this material be considered as final code that can be used without proper precautions.

To begin, let's take the code from the previous article, as it contains something I find quite practical and easy to understand in relation to what we will do here. The version we will use is shown below:

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. struct st_Data 05. { 06. //+----------------+ 07. private: 08. //+----------------+ 09. double Values[]; 10. //+----------------+ 11. public: 12. //+----------------+ 13. void Set(const double &arg[]) 14. { 15. ArrayFree(Values); 16. ArrayCopy(Values, arg); 17. } 18. //+----------------+ 19. double Average(void) 20. { 21. double sum = 0; 22. 23. for (uint c = 0; c < Values.Size(); c++) 24. sum += Values[c]; 25. 26. return sum / Values.Size(); 27. } 28. //+----------------+ 29. double Median(void) 30. { 31. double Tmp[]; 32. 33. ArrayCopy(Tmp, Values); 34. ArraySort(Tmp); 35. if (!(Tmp.Size() & 1)) 36. { 37. int i = (int)MathFloor(Tmp.Size() / 2); 38. 39. return (Tmp[i] + Tmp[i - 1]) / 2.0; 40. } 41. return Tmp[Tmp.Size() / 2]; 42. } 43. //+----------------+ 44. }; 45. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 46. #define PrintX(X) Print(#X, " => ", X) 47. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 48. void OnStart(void) 49. { 50. const double H[] = {2.05, 1.97, 1.87, 1.75, 1.99, 2.01, 1.83}; 51. const double K[] = {12, 4, 7, 23, 38}; 52. 53. st_Data Info; 54. 55. Info.Set(H); 56. PrintX(Info.Average()); 57. 58. Info.Set(K); 59. PrintX(Info.Median()); 60. } 61. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 01

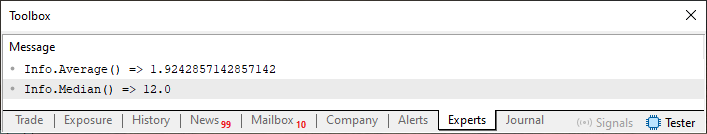

By executing code 01 in the MetaTrader 5 platform, we will get the following result:

Figure 01

Nothing particularly special yet. But consider the following situation: code 01 is implemented to tell us two things: the average value and the median of an array of values. However, it can only do this with floating-point values, specifically double values, because it doesn't understand float values, even though that is also a floating-point data type. Not to mention integer values.

In this case, despite its apparent practicality, code 01 is largely useless, because to work with numeric data types other than double, we would have to implement the structure over and over again until all numeric data types are covered.

Such situations are known as overloading. However, overloading structures does not work the same way as overloading functions and procedures. In this case, when performing overloading, we would have to change the structure's name, i.e., the information processed in line 04 of code 01.

And as a result, we would create a series of new structures with the same purpose, context, and encapsulated data, but with completely different names. In other words, complete chaos and a huge amount of work.

Programmers, and I speak from experience, do not like extra work. If we have to repeat code more than once, we start to get bored and lose interest. We love thinking about solving problems. But duplicating code just to change one detail is not to our liking. I definitely hate doing it. Other programmers, like me, have also figured out how to solve such a problem and created a mechanism that allows overloading of what cannot be overloaded. That's how the idea of using structure templates was born.

In their basic form, we have already explained templates in a short series of five articles, the first of which is "From Basic to Intermediate: Template and Typename (I)". So, it is very important that you have a good grasp of all the knowledge and concepts explained there to understand what will be done now. This is because what was explained earlier remains unclear. What we are about to do now doesn't make any sense.

But what we are going to show is the simplest and easiest way to work with structure overloading, although there are other ways, much more complex and with very specific goals. I will consider whether it's worth creating an article to show other methods. In any case, the simplest way will be to use a template.

So, let's take a step back, because before considering applying a structure template to a structured implementation, we must see how it applies to a more general structure. In other words, we need to examine how a structure template is used in regular code. To do this, we will change code 01 from structural to regular. The final result will be as follows:

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. struct st_Data 05. { 06. double Values[]; 07. }; 08. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 09. double Average(const st_Data &arg) 10. { 11. double sum = 0; 12. 13. for (uint c = 0; c < arg.Values.Size(); c++) 14. sum += arg.Values[c]; 15. 16. return sum / arg.Values.Size(); 17. } 18. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 19. double Median(const st_Data &arg) 20. { 21. double Tmp[]; 22. 23. ArrayCopy(Tmp, arg.Values); 24. ArraySort(Tmp); 25. if (!(Tmp.Size() & 1)) 26. { 27. int i = (int)MathFloor(Tmp.Size() / 2); 28. 29. return (Tmp[i] + Tmp[i - 1]) / 2.0; 30. } 31. return Tmp[Tmp.Size() / 2]; 32. } 33. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 34. #define PrintX(X) Print(#X, " => ", X) 35. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 36. void OnStart(void) 37. { 38. const double H[] = {2.05, 1.97, 1.87, 1.75, 1.99, 2.01, 1.83}; 39. const double K[] = {12, 4, 7, 23, 38}; 40. 41. st_Data Info_1, 42. Info_2; 43. 44. ArrayCopy(Info_1.Values, H); 45. PrintX(Average(Info_1)); 46. 47. ArrayCopy(Info_2.Values, K); 48. PrintX(Median(Info_2)); 49. } 50. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 02

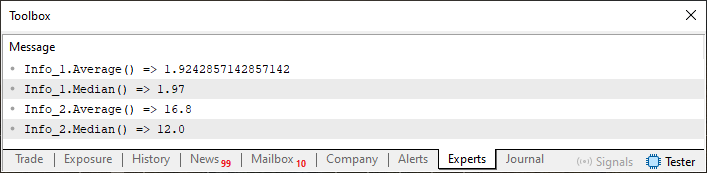

Alright, now code 02 has a regular format. When executed in MetaTrader 5, we will get the following result:

Figure 02

Well then, considering everything that has been explained up to this point, I am confident you will easily understand what code 02 does and how it works. In the same way we can work with a floating-point type, we can implement function and procedure templates here. Thus, code 02 will become as follows:

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. struct st_Data 06. { 07. double Values[]; 08. }; 09. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 10. template <typename T> 11. double Average(const st_Data <T> &arg) 12. { 13. T sum = 0; 14. 15. for (uint c = 0; c < arg.Values.Size(); c++) 16. sum += arg.Values[c]; 17. 18. return sum / arg.Values.Size(); 19. } 20. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 21. template <typename T> 22. double Median(const st_Data <T> &arg) 23. { 24. T Tmp[]; 25. 26. ArrayCopy(Tmp, arg.Values); 27. ArraySort(Tmp); 28. if (!(Tmp.Size() & 1)) 29. { 30. int i = (int)MathFloor(Tmp.Size() / 2); 31. 32. return (Tmp[i] + Tmp[i - 1]) / 2.0; 33. } 34. return Tmp[Tmp.Size() / 2]; 35. } 36. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 37. #define PrintX(X) Print(#X, " => ", X) 38. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 39. void OnStart(void) 40. { 41. const double H[] = {2.05, 1.97, 1.87, 1.75, 1.99, 2.01, 1.83}; 42. const uchar K[] = {12, 4, 7, 23, 38}; 43. 44. st_Data <double> Info_1; 45. st_Data <uchar> Info_2; 46. 47. ArrayCopy(Info_1.Values, H); 48. PrintX(Average(Info_1)); 49. 50. ArrayCopy(Info_2.Values, K); 51. PrintX(Median(Info_2)); 52. } 53. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 03

«What a cosmic complication. Friend, what is this insane and crazy code? Do we really need to go through this?» Calm down, this code isn't as crazy as the one that uses memory manipulation. So, I'll consider whether it's worth showing how to implement structure overloading via memory manipulation. However, much of code 03 will already be familiar and understandable to you. Perhaps lines 44 and 45 are the only ones that might hold some surprise.

Incidentally, something similar was discussed in the article "From Basic to Intermediate: Template and Typename (IV)", but not regarding the use of structures, rather regarding the use of unions. In any case, the working principles are the same. And since everything was already explained there, I see no need to explain the same concept again, especially since it was necessary to do so across two articles.

So, if you don't understand what's happening in code 03, I advise you to go back to the previous articles. As I've said, knowledge accumulates over time. Trying to skip stages, thinking you can understand something more complex without first grasping the basic concepts, rarely leads to a good outcome.

Alright, but there's a small detail here that, at first glance, might not be irritating: the data type returned by the median. The problem here is related to the fact that if the array contains an even number of elements, the test in line 28 will change the flow so that line 32 is executed. But if the number of elements is odd, line 34 will be executed, which in many cases will result in a value different from what might be expected.

This happens because an array with integer elements should not, in principle, return a floating-point value, as is the case here. Therefore, the result printed to the terminal doesn't quite match the values of the array declared in line 42, since the array has integer elements, but the returned value is of a floating-point type. But since this code is purely educational, I prefer to leave this minor discrepancy rather than show a completely incorrect result.

Thus, looking at code 03 and thinking about how to transform it into something similar to code 01, which has a structural implementation, it's easy to spot the correct path because it's enough to modify code 01 so that the template declaration shown in code 03 is executed.

But you might be concerned about the fact that in code 03 we had to implement the functions as templates. «So, do we need to do the same with code 01 so that the structural implementation works correctly and the compiler knows how to overload the structure?" Well, in this case, it won't be necessary because the context itself is quite simple and there isn't much to add to it.

However, unlike code 03, where we pass the structure's values by reference, in code 01 this is not possible. The reason for this was already explained in the previous article, where the issue of context was considered along with the issue of data encapsulation. The only way to introduce new values is through the Set procedure, which is present in code 01. Therefore, this point will be one of the few where we will have to implement something different from what originally exists in code 01. Thus, below we show the new code 01, already accounting for structure overloading.

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. struct st_Data 06. { 07. //+----------------+ 08. private: 09. //+----------------+ 10. T Values[]; 11. //+----------------+ 12. public: 13. //+----------------+ 14. void Set(const T &arg[]) 15. { 16. ArrayFree(Values); 17. ArrayCopy(Values, arg); 18. } 19. //+----------------+ 20. double Average(void) 21. { 22. double sum = 0; 23. 24. for (uint c = 0; c < Values.Size(); c++) 25. sum += Values[c]; 26. 27. return sum / Values.Size(); 28. } 29. //+----------------+ 30. double Median(void) 31. { 32. T Tmp[]; 33. 34. ArrayCopy(Tmp, Values); 35. ArraySort(Tmp); 36. if (!(Tmp.Size() & 1)) 37. { 38. int i = (int)MathFloor(Tmp.Size() / 2); 39. 40. return (Tmp[i] + Tmp[i - 1]) / 2.0; 41. } 42. return (double) Tmp[Tmp.Size() / 2]; 43. } 44. //+----------------+ 45. }; 46. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 47. #define PrintX(X) Print(#X, " => ", X) 48. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 49. void OnStart(void) 50. { 51. const double H[] = {2.05, 1.97, 1.87, 1.75, 1.99, 2.01, 1.83}; 52. const char K[] = {12, 4, 7, 23, 38}; 53. 54. st_Data <double> Info_1; 55. st_Data <char> Info_2; 56. 57. Info_1.Set(H); 58. PrintX(Info_1.Average()); 59. PrintX(Info_1.Median()); 60. 61. Info_2.Set(K); 62. PrintX(Info_2.Average()); 63. PrintX(Info_2.Median()); 64. } 65. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 04

Please note how straightforward it is to transform code 01 into code capable of creating structural overloads, ultimately resulting in fully structural code. Since the functions and procedures are declared within the structure's context, they inherit its own declaration. This happens when the compiler proceeds to implement the overloading of the structure itself.

As mentioned earlier, the issue with return values arises precisely because at some points we will be converting integer values to floating-point values, specifically of type double, which in some cases can become problematic. This can be seen in lines 20 and 30 of code 04. «But wait a second. I don't understand why this could be a problem. And if it is, is there a way to overcome it to avoid unnecessary risks?»

Well, to understand this, we first need to see what the result of executing code 04 will be. See below:

Figure 03

Now, pay attention to a detail present in image 03. Notice that the value returned by Info_2.Median is a floating-point value, but Info_2, when declared in the code, is of type integer, as seen in line 55. The problem lies in the fact that the structure does not handle such a situation well when we ask it to return the median value present within the data structure itself, and the system ends up returning a different type. More correctly, it should return an integer value, but we are returning a floating-point one.

Such issues, which may seem easy to solve, turn out to be much more complex in practice and in real code. However, primarily, many programmers (and I say this in a general sense) use a methodology where they add more and more functions and procedures to solve some internal problem of the structure itself. In most cases, this solves the problem, although it often leads to solutions or implementations that don't make much sense to other programmers in principle. The reason is simple: the best way to solve a problem is not to solve it, but to provide mechanisms that allow thinking about it in terms of smaller parts.

«But how is that? There seems to be some contradiction». To understand this, we need to use code 04 as a teaching mechanism. «First point: why do we need to return the average value directly via a function?» One could answer that the code will be simpler by using the structure itself. In fact, that would be a good argument.

But let's return to the case of integers, as in the statement on line 55. The average of the elements we place there, i.e., in line 61, is actually a floating-point value, in this case, 16.8. But consider a situation where we need an average value that should be an integer. That would require rounding. There are rounding rules for such situations, but this is not that case.

The goal is for the programmer using this structure to know how, when, and why to round the value. The task is to obtain an integer value.

To achieve this, we need to change the context of what we implement in the structure. Often, we do not remove parts of the code but add new ones to it, thereby creating smaller and more precise blocks. To better understand this, let's look at a practical example. As you can see, in line 20 of code 04, we have a function that calculates the average of the structure's own values. Nothing extraordinary so far.

However, note that to get this average, we need to do two things: first, find the sum of the elements, and second, find out how many elements there are in total. Now, you might be thinking: «Right, what's next?» If, instead of doing this directly in the Average function, we create two other functions, we can allow the user of the structure to choose how, where, and why to round the average values of the structure's elements.

I don't know if you've got the gist, dear readers, but let's see how this is done in practice. For this, we will use the following code:

01. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 02. #property copyright "Daniel Jose" 03. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 04. template <typename T> 05. struct st_Data 06. { 07. //+----------------+ 08. private: 09. //+----------------+ 10. T Values[]; 11. //+----------------+ 12. public: 13. //+----------------+ 14. void Set(const T &arg[]) 15. { 16. ArrayFree(Values); 17. ArrayCopy(Values, arg); 18. } 19. //+----------------+ 20. T Sum(void) 21. { 22. T sum = 0; 23. 24. for (uint c = 0; c < NumberOfElements(); c++) 25. sum += Values[c]; 26. 27. return sum; 28. } 29. //+----------------+ 30. uint NumberOfElements(void) 31. { 32. return Values.Size(); 33. } 34. //+----------------+ 35. double Average(void) 36. { 37. return ((double)Sum() / NumberOfElements()); 38. } 39. //+----------------+ 40. double Median(void) 41. { 42. T Tmp[]; 43. 44. ArrayCopy(Tmp, Values); 45. ArraySort(Tmp); 46. if (!(Tmp.Size() & 1)) 47. { 48. int i = (int)MathFloor(Tmp.Size() / 2); 49. 50. return (Tmp[i] + Tmp[i - 1]) / 2.0; 51. } 52. return (double) Tmp[Tmp.Size() / 2]; 53. } 54. //+----------------+ 55. }; 56. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 57. #define PrintX(X) Print(#X, " => ", X) 58. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ 59. void OnStart(void) 60. { 61. const double H[] = {2.05, 1.97, 1.87, 1.75, 1.99, 2.01, 1.83}; 62. const char K[] = {12, 4, 7, 23, 38}; 63. 64. st_Data <double> Info_1; 65. st_Data <char> Info_2; 66. 67. Info_1.Set(H); 68. PrintX(Info_1.Average()); 69. PrintX(Info_1.Median()); 70. 71. Info_2.Set(K); 72. PrintX(Info_2.Average()); 73. PrintX(Info_2.Sum()); 74. PrintX(Info_2.NumberOfElements()); 75. PrintX(Info_2.Sum() / Info_2.NumberOfElements()); 76. PrintX(Info_2.Median()); 77. } 78. //+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Code 05

So, in code 05, we are modeling something that many think only happens when working with OOP, but which originated in structural programming: breaking code down into small blocks. Please note that in line 20 of this code, we now have a function whose purpose is to return the sum of all elements in the structure. The return type depends on the kind of data contained within the structure itself. Pay attention to this, as its important. We also have another function, located in line 30, whose purpose is to return the number of elements in the structure itself.

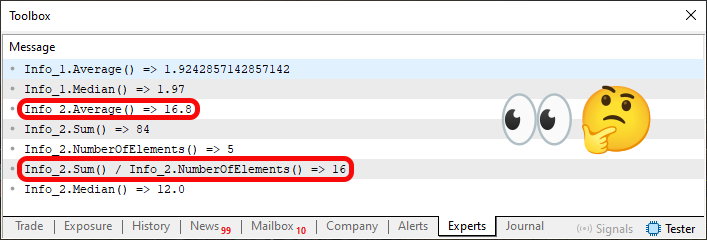

Now, the most interesting part begins. Since the average is calculated by dividing these two quantities, which we compute in the functions mentioned above, in line 37 we have a calculation oriented towards the structure's context. But this is the key point. Please note that we instruct the compiler to convert the result of the Sum function to the double type. Why do this? The answer can be seen in the execution image of code 05. Here it is:

Figure 04

In this image, two fragments of information stand out: one corresponds to the execution of line 72, and the other to line 75. Nevertheless, please note that these two presented data types are different. One is floating-point, and the other is integer. Below, we explain why the result of the Sum function is converted to double in line 37. Note that the same calculation performed in line 37 is repeated in line 75, but in one case, the value 84, which would be the result of summing the elements in line 62, is converted to double, and in the other, it is not. Therefore, although the context allows us to calculate the average directly within the structure, as done in line 37, we can also do it outside the structure. This is precisely why we can control what the result will look like in terms of the data type used.

This may seem absurd, but notice that without changing the essence of things, we have given the programmer the ability to control, adjust, and even choose how the result is represented—something that would otherwise be much more difficult and time-consuming. All this was achieved simply by moving calculations (previously done in one function) into several functions accessible outside the structure's body. Yet, in doing so, we manage to preserve the context of the structure itself because, looking at line 75, we understand what kind of information we need.

If you study things like this, you will understand that in most cases, this is what we mean when we talk about classes and object-oriented programming. However, with this simple code, we have shown that this concept exists independently of OOP. Thus, when in the future you are told about this programming model, you will already have a good foundation because you will see that OOP is aimed precisely at filling the gaps that structured programming cannot address.

«Alright, that was interesting, but could we do something else without overcomplicating things?» Yes, my dear reader. There is a concept—although not necessarily a concept, but rather a technique that various programmers use in their code to simplify much of what we've seen here. But if you don't understand what was discussed here, it will be difficult for you to grasp what we can do to create structural overloading. It's worth remembering that the overloading we've been discussing is aimed at creating a more general structure, but with a very specific context.

Since we still have a little time, I can briefly outline what the aforementioned maneuver will entail. But for that, we need to pause and consider a few points. First, note that in lines 64 and 65 of code 05, there is a statement whose purpose is to store discrete data- i.e., values that can be integers or floating-point numbers. However, if you think about it, unions and structures are also forms of data, so they too can be declared as a data type to be used in a structure whose code will be overloaded to build a model suitable for that specific data type.

I think you've already grasped this and have likely practiced it in the articles where we discussed how overloading and the use of templates in code work. However, unlike discrete data types, types such as unions and structures are more complex, as they can contain a wide variety of things. Take, for example, the MqlRates structure. It defines elements such as open price, close price, spread, volume, and so on. Therefore, although in principle we can declare a structure template capable of accepting any type of information, be it complex or discrete values, there are complicating factors that prevent us (though that's not the most suitable word) from defining complex types where discrete types were expected. But this doesn't stop us from creating specific mechanisms necessary for solving particular tasks in a less costly way.

So, I want you to think about how we could use data such as unions or structures in code similar to that in code 05, to generalize, in various ways, the overloading of the structure and thus build fully structural code. I know it's not the easiest task, but I want you to ponder this because, in the next article, we will explore precisely what is related to this.

Concluding thoughts

In this article, we tried to explain how to overload structural code in the simplest, most didactic, and practical way. I know it can be quite challenging to understand at first, especially if you're seeing it for the first time. It is very important that you grasp these concepts and understand them well before attempting to delve into more complex and elaborate topics.

In the appendix, you will find the codes for study and practice. In the next article, we will raise the bar even higher by extending this type of implementation to cases where we can use any data type in the structure overloading itself—something many believe is only possible in OOP. But you will see that to implement certain types of solutions, we still don't need OOP. So, best of luck in your studies! See you soon.

Translated from Portuguese by MetaQuotes Ltd.

Original article: https://www.mql5.com/pt/articles/15869

Warning: All rights to these materials are reserved by MetaQuotes Ltd. Copying or reprinting of these materials in whole or in part is prohibited.

This article was written by a user of the site and reflects their personal views. MetaQuotes Ltd is not responsible for the accuracy of the information presented, nor for any consequences resulting from the use of the solutions, strategies or recommendations described.

From Basic to Intermediate: Struct (VI)

From Basic to Intermediate: Struct (VI)

Market Simulation: (Part 11): Sockets (V)

Market Simulation: (Part 11): Sockets (V)

Features of Experts Advisors

Features of Experts Advisors

Market Simulation (Part 14): Sockets (VIII)

Market Simulation (Part 14): Sockets (VIII)

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use