From Novice to Expert: Demystifying Hidden Fibonacci Retracement Levels

Contents:

Introduction

Fibonacci retracement levels are widely used but, sometimes price reacts to intermediate or repeated non-standard ratios. Our question is, can we use systematic, data-driven methods to discover such levels, test whether they occur more often than once, and, if robust, add them as first-class levels in our trading tools and strategies?

Why traditional Fibonacci levels may be incomplete

Classical Fibonacci ratios such as 23.6%, 38.2%, 50%, 61.8%, and 78.6% are derived from the Fibonacci sequence and the golden ratio. While widely accepted, traders often notice that markets sometimes respect intermediate or alternative retracement levels not included in this traditional set. This suggests the standard framework may not fully capture market behavior.

Observations of hidden market reactions

Anecdotally, price often stalls, reverses, or accelerates near levels between 50% and 61.8% or around other non-standard points. Let's consider calling these “hidden” Fibonacci levels. The difficulty is that such observations are subjective, based on visual inspection of charts, and may not hold consistently across instruments or timeframes.

The challenge of anecdotal evidence vs. statistical proof

Visual pattern recognition is prone to confirmation bias: we remember the times when price reacted at a suspected level but forget the misses. Without systematic testing, these hidden levels remain speculative. Still, anecdotal evidence gives us a starting point to test these ideas in a structured way and bring more accuracy to the theory traders rely on. The challenge is to distinguish genuine structural tendencies from randomness and noise.

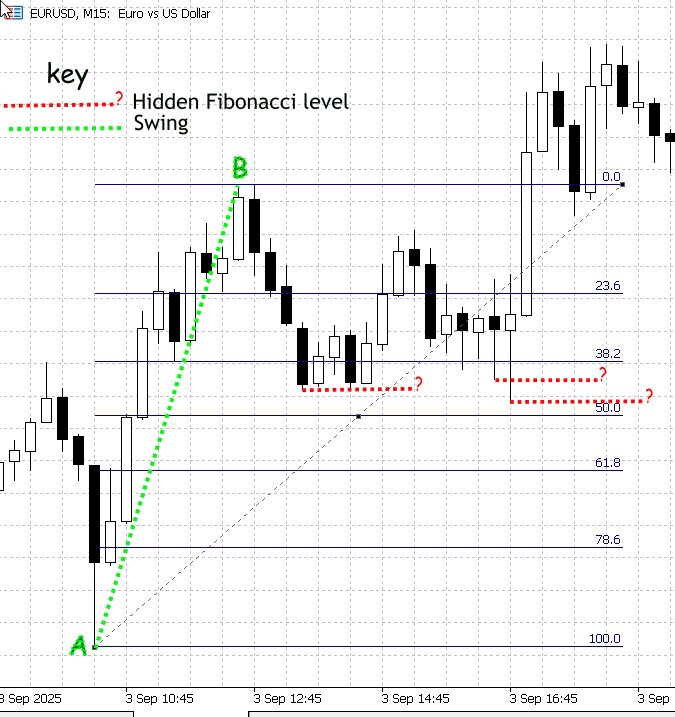

Figure 1. Demonstrating non-standard Fibonacci retracement levels

Figure 1 (above) is a screenshot from MetaTrader 5 showing EURUSD on the M15 timeframe. Swing A–B was measured with the Fibonacci tool; the standard retracement levels are drawn in blue and labelled. Price did not stop exactly on those classical ratios—instead, you can see distinct price activity at intermediate points between the marked levels (38.2 and 50). I highlighted those intermediate reactions with red dashed lines and labelled them “?” to indicate they are unknown, potentially meaningful levels.

Those intermediate reactions are precisely what our research aims to resolve. Although we could compute and draw precise retracement values programmatically, manual inspection is unreliable because the built-in Fibonacci tool only plots the textbook ratios. What’s required is a two-stage process: first, collect and statistically filter a large set of normalized retracement observations to identify which intermediate bands are repeatedly respected; second, implement an algorithm that calibrates and renders those validated levels on the MetaTrader 5 Fibonacci tool (annotated with confidence scores).

Implementation Strategy

Bar-range and swing detection methods

For this project, each bar’s high and low are treated as a simple “swing” range. We apply a minimum-range filter (for example, an ATR multiplier) to suppress noise and focus on meaningful moves. This bar-range proxy is intentionally lightweight: it is simple to implement, fast to run over large histories, and yields a deterministic, one-observation-per-closed-bar dataset that is ideal for statistical discovery.

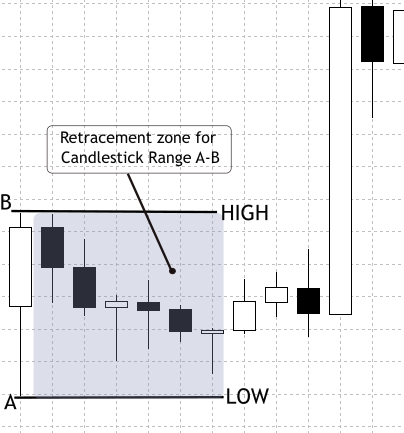

In future phases we will adopt more refined multi-bar swing detection to capture longer or structurally significant swings. The present choice—to start with bar ranges—is deliberate: it minimizes engineering overhead so we can quickly collect large samples, validate our statistical methods, and then iterate. The feasibility of the approach rests on a practical market observation: candlesticks frequently retrace a portion of the prior move, producing measurable peaks in a normalized retracement distribution. See Figure 2 for an illustration of intrabar retracement behavior, which serves as the motivation for this method.

Figure 2. Candlestick Bar-Range Retracement

Data collection and preparation

The first step is to gather historical OHLCV data across multiple instruments (e.g., EURUSD, GBPUSD, S&P500, XAUUSD) and timeframes (M15, H1, H4, D1). A sufficiently deep sample—ideally three to five years of data—ensures that diverse market regimes are represented, from trending phases to consolidations. Data must also be cleaned before use, filtering out missing bars, abnormal spikes, and gaps that could bias the analysis. This foundation guarantees that the retracement dataset reflects genuine market structure rather than random anomalies.

Building on this clean base, each closed bar is treated as a self-contained swing range. The high and low define the reference boundaries, and the very next bar is examined for its retracement depth. To suppress noise, ranges smaller than an ATR-based threshold are excluded. The retracement percentage is then normalized to a 0–100 scale and logged alongside metadata such as symbol, timeframe, direction, timestamp, and volume. Crucially, not all sequences are accepted: the collector rejects invalid cases where the test bar opens outside the prior range or closes against the reference bar’s direction. Extended-window logic collapses consecutive inside bars or flags, engulfing patterns and gaps, ensuring they are not mistaken for ordinary retracements. By applying these validations and capturing metadata, the resulting dataset is both clean and reproducible—ready for statistical exploration of classical Fibonacci ratios as well.

Developing a Data Collection Script

In the next stages, we will prepare our data collection script in MQL5 and use it to generate a retracement CSV data file. This file will then be analyzed in Jupyter Notebook to explore patterns and extract insights.

Initialization—we set the controls and helpers

At the top we declare all the parameters that control behavior: how many bars to examine, ATR settings, lookahead limits, and output flags. When the script starts, it reads these inputs and prepares two small helpers (a formatter and a timeframe-to-string mapper) so other code stays tidy. The script then builds an output filename that includes symbol and timeframe and opens a CSV file for writing. If the file can’t be opened, it stops and reports the error—so we always know whether the run actually started.

//--- input parameters input int BarsToProcess = 20000; // how many candidate reference bars to process input int StartShift = 1; // skip most recent N bars input int ATR_Period = 14; // ATR period input double ATR_Multiplier = 0.3; // min ATR filter input int MaxLookahead = 3; // extended-window lookahead input bool UsePerfectSetup = true; // require perfect setups input bool OutputOnlySameDir = false; // require same-dir support input bool IncludeInvalidRows= false; // output invalids input string OutFilePrefix = "CandleRangeData"; // file prefix //--- output file string OutFileName = StringFormat("%s_%s_%s.csv", OutFilePrefix, _Symbol, PeriodToString(_Period)); int fh = FileOpen(OutFileName, FILE_WRITE|FILE_CSV|FILE_ANSI); if(fh == INVALID_HANDLE) { PrintFormat("Error opening file %s", OutFileName); return; }

Volatility baseline—we create an ATR handle so the script can filter noise

Before scanning bars, we create an ATR indicator handle. For every candidate reference bar, the script will read ATR at that bar; the ATR value functions as a volatility yardstick. If a bar’s range is smaller than ATR * ATR_Multiplier, the script treats the bar as noise and skips it. Removing tiny ranges prevents small random bars from producing spurious retracement entries. It raises signal quality.

//--- prepare ATR handle int atr_handle = iATR(_Symbol, _Period, ATR_Period); if(atr_handle == INVALID_HANDLE) { Print("ATR handle invalid"); FileClose(fh); return; }

Main scan loop—the script walks the history

The script iterates closed bars backwards from StartShift up to the available history or until it writes BarsToProcess rows. For each iteration (each candidate reference bar), the script reads the reference bar’s High, Low, Open, and Close, computes the Range, and immediately applies the ATR gate. If the bar passes, the script moves to analyze the test bar(s) that follow the reference. This loop is the engine that turns raw history into candidate retracement events. By this we reduce bad cases early to improve downstream statistics.

int bars = iBars(_Symbol,_Period); double atr_buf[]; for(int r = StartShift; r <= bars - 1; r++) { double RefTop = iHigh(_Symbol,_Period,r); double RefBot = iLow(_Symbol,_Period,r); double RefOpen = iOpen(_Symbol,_Period,r); double RefClose = iClose(_Symbol,_Period,r); double Range = RefTop - RefBot; // ATR filter if(CopyBuffer(atr_handle,0,r,1,atr_buf) <= 0) continue; if(Range < atr_buf[0] * ATR_Multiplier) continue; // process this reference... }

Determine reference direction—we label the swing as Bull/Bear/Neutral

For the reference bar we check whether it closed higher than it opened (Bull), lower than it opened (Bear), or equal (Neutral). That direction decides which extreme in the test bar represents a retracement (a bullish reference looks for lows; a bearish one looks for highs). Normalization of retrace percent depends on whether the reference was up or down.

string RefDir; if(RefClose > RefOpen) RefDir = "Bull"; else if(RefClose < RefOpen) RefDir = "Bear"; else RefDir = "Neutral";

Initial test bar & perfect-setup validation—we verify the simple, clean cases first

The script reads the immediate next bar (test bar) after the reference; this bar is where the retracement usually happens. If we enabled the “perfect setup” filter, the script checks two trader-style conditions: the test bar must open inside the reference range, and its close must not be against the reference direction (e.g., for a bullish reference, the test bar should not close bearish). If the test bar fails and we don’t want diagnostic rows, the script skips writing anything for this reference.

int testIndex = r - 1; double testOpen = iOpen(_Symbol,_Period,testIndex); double testClose= iClose(_Symbol,_Period,testIndex); bool ValidSetup = true; if(UsePerfectSetup) { if(testOpen < RefBot || testOpen > RefTop) ValidSetup = false; if(RefDir=="Bull" && testClose < testOpen) ValidSetup = false; if(RefDir=="Bear" && testClose > testOpen) ValidSetup = false; } if(!ValidSetup && !IncludeInvalidRows) continue;

Extended-window handling—we let the script capture realistic multi-bar retracements

When enabled, the script looks further back (a configurable number of bars) to collapse short sequences that together produce the true retracement extreme. It does three things while scanning lookahead bars:

- Detect gaps—if a bar opens outside the reference range, the script flags a gap and records its size.

- Collapse inside bars—if several small consecutive bars sit entirely inside the reference range, the script updates the extreme (Ext) to the worst low (for Bull) or worst high (for Bear) across those bars and increments InsideCount.

- Detect engulfing bars—if a later bar fully engulfs the reference, the script classifies it as Engulf and sets a HighMomentum flag.

This collapsing ensures the observation represents the completed retracement episode rather than a premature partial touch.

double Ext = (RefDir=="Bull") ? testLow : testHigh; string SeqType = "Single"; bool HighMomentum = false; int InsideCount = 0; for(int k=1; k<=MaxLookahead; k++) { int idx = r - k; if(idx < 0) break; double kOpen = iOpen(_Symbol,_Period,idx); double kHigh = iHigh(_Symbol,_Period,idx); double kLow = iLow(_Symbol,_Period,idx); if(kOpen > RefTop || kOpen < RefBot) { SeqType="Gap"; break; } if(kHigh <= RefTop && kLow >= RefBot) { if(RefDir=="Bull") Ext = MathMin(Ext,kLow); if(RefDir=="Bear") Ext = MathMax(Ext,kHigh); InsideCount++; continue; } if(kHigh >= RefTop && kLow <= RefBot) { SeqType="Engulf"; HighMomentum=true; break; } // if retrace detected, stop break; }

Computing retracement percentage—script normalizes the result for analysis

Using the final recorded extreme (Ext), the script computes RetracePct on a 0–100 scale:

- For Bull reference: RetracePct = (RefTop - Ext) / Range * 100

- For Bear reference: RetracePct = (Ext - RefBot) / Range * 100

Then it labels the event:

- NoRetrace if negative (price moved away),

- Retracement if between 0 and 100,

- Extension if above 100 (price moved beyond the reference).

double Rpct = EMPTY_VALUE; string Type = "Undefined"; if(RefDir=="Bull") Rpct = (RefTop - Ext) / Range * 100.0; if(RefDir=="Bear") Rpct = (Ext - RefBot) / Range * 100.0; if(Rpct < 0) Type="NoRetrace"; else if(Rpct<=100) Type="Retracement"; else Type="Extension";

Practical diagnostics—compute tradeable distance and closeness to classic fibonacci levels

We calculate RetracePips, the absolute number of pips the retrace represents, so we can discard trivial, untradable touches (e.g., smaller than the spread). We also compute which classical Fibonacci level is closest and how far (NearestFibPct, NearestFibDistPct). Finally, we set SameDirSupport by checking whether the representative bar (the last bar in the collapsed sequence) closed in the same direction as the reference.

double RetracePips = (RefDir=="Bull") ? (RefTop-Ext)/_Point : (Ext-RefBot)/_Point; // Same-dir support bool SameDirSupport = (RefDir=="Bull") ? (testClose >= testOpen) : (testClose <= testOpen); // Nearest Fibonacci comparison double fibLevels[] = {0,23.6,38.2,50.0,61.8,78.6,100.0}; double nearest = fibLevels[0]; double minDist = fabs(Rpct - fibLevels[0]); for(int i=1;i<ArraySize(fibLevels);i++) { double d = fabs(Rpct - fibLevels[i]); if(d < minDist) { minDist = d; nearest = fibLevels[i]; } }

Output rules

Based on flags (OutputOnlySameDir, IncludeInvalidRows), the script either skips or writes the row. If it writes, the row contains all metadata (time, symbol, RefTop/RefBot, Ext, RetracePips, RetracePct, SeqType, SameDirSupport, nearest fib match, volume and spread). The file is deterministic: the same symbol, timeframe, and parameters always produce the same CSV.

if(OutputOnlySameDir && !SameDirSupport) continue; FileWrite(fh, _Symbol, PeriodToString(_Period), TimeToString(iTime(_Symbol,_Period,r),TIME_DATE|TIME_SECONDS), RefTop, RefBot, Range, RefDir, Ext, RetracePips, Rpct, Type, SeqType, HighMomentum, InsideCount, SameDirSupport, nearest, minDist );

Cleanup and reporting—we finish the run and tell the team what happened

After the loop, the script releases the ATR handle, closes the file, and prints a short summary telling how many rows were written and how many invalid candidates were skipped. This immediate feedback guides our next action (e.g., increase bars, loosen filters, or change ATR multiplier).

IndicatorRelease(atr_handle); FileClose(fh); PrintFormat("CandleRangeData_v2: finished. Wrote %d rows to %s", written, OutFileName);

Statistical Analysis and Visualization of Fibonacci Retracement Data with Python in Jupyter Notebook

To advance our research, we will use Python to refine the data and generate statistical reports. For this purpose, I have chosen Jupyter Notebook, as it provides an enhanced workflow for Python and supports the type of results we aim to achieve.

Jupyter Notebook is an interactive web environment designed for scientific computing, data analysis, and visualization. It allows code, visual outputs, and documentation to coexist in the same workspace, making it particularly effective for research-driven tasks. In our case, this environment offers the flexibility to experiment with retracement data, test statistical methods, and instantly visualize outcomes such as histograms and density plots. Unlike a static script that must run from start to finish, Jupyter enables us to execute small cells independently—a valuable advantage when adjusting calculations or re-running specific steps without restarting the entire process. This interactive workflow fits well with the iterative and exploratory nature of mining patterns in financial data.

The following outline provides the steps for setting up Jupyter Notebook on Windows.

To run the cells below, use Jupyter (Notebook or Lab) on Windows. The steps are:

1. Install Python 3.10+ from python.org (choose “Add Python to PATH”).2. Open a command prompt (PowerShell or CMD) and create a virtual environment (optional but recommended):

python -m venv venv venv\Scripts\activate3. Install Jupyter and required libraries:

pip install jupyter pandas numpy matplotlib scipy scikit-learn

4. Start Jupyter:

If you want to work within a specific folder, use the cd command to change the directory. For example, to navigate to a folder where the CSV file is exported, generally C:\Users\YourComputerName\MQL5\Files, you would type:

cd C:\Users\YourComputerName\TerminalDataFolder\MQL5\Files After that, you can launch it using

jupyter notebook

Libraries and their purpose

- pandas—load and manipulate the CSV table (rows/columns).

- numpy—numeric arrays and helper math.

- matplotlib—plotting histograms and KDEs.

- scipy—statistical functions and KDE.

- scikit-learn (sklearn)—Gaussian Mixture Models for 1-D clustering.

Cell 1—Setting Up Python Enviroment

At the start of our notebook, we prepare the environment by importing the Python libraries that will power our analysis. Each library plays a specialized role in handling the data exported from the MQL5 script.

- Pandas (pd) is used for structured data handling. It allows us to load the CSV file containing retracement records, manipulate rows and columns, and easily compute statistics.

- Numpy (np) provides mathematical tools and numerical operations, such as arrays and linear algebra, which underlie many of our statistical calculations.

- Matplotlib.pyplot (plt) is the foundation for plotting charts like histograms and density plots, which will help us visualize retracement behavior.

- Seaborn (sns) builds on matplotlib to provide more elegant and easier-to-style plots, making statistical patterns clearer.

- Scipy.stats (stats) brings in advanced statistical methods such as kernel density estimation (KDE), hypothesis testing, and probability distributions.

- Sklearn.mixture.GaussianMixture comes from the scikit-learn machine learning library and allows us to fit Gaussian mixture models. This is useful when clustering retracement levels to detect where hidden Fibonacci-like levels may be concentrated.

By running this cell, we effectively load all the tools needed for our work.

import pandas as pd import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import seaborn as sns from scipy import stats from sklearn.mixture import GaussianMixture

Cell 2—Load CSV and create a boolean ValidSetup_bool column

At this point in the notebook, the script begins by loading the retracement dataset exported from MQL5. The CSV file is read into a pandas DataFrame, and the program immediately prints how many rows were loaded and which columns are available. This is an important checkpoint because it confirms that the file path is correct and that the expected fields, such as RetracementPct, Type, or ValidSetup, exist. To help us visualize the structure, the script also displays the first few rows so we can quickly check the data looks consistent with what we expect from our MetaTrader export.

Once the dataset is in memory, the next task is to decide which rows are valid for further analysis. The issue is that not all retracement calculations from the MQL5 script should be trusted: some may be incomplete or flagged as invalid setups. Because datasets can use slightly different column names for validity (like ValidSetup, Valid, or validsetup), the script searches across several common variants. If one is found, it standardizes the results into a new boolean column called ValidSetup_bool. Values such as “True,” “1,” or “Yes” are interpreted as valid. If no validity column is found at all, the script defaults to treating all rows as valid, ensuring that we still have data to work with. Finally, a filtered dataset called df_valid is created, containing only valid rows, and quick statistics are printed to show how many total rows were loaded versus how many passed the validity filter.

# Robust Cell 2: load CSV and create a boolean ValidSetup_bool column import pandas as pd from IPython.display import display csv_file = "CandleRangeData_NZDUSD_H4.csv" # <- set your filename here df = pd.read_csv(csv_file, sep=None, engine="python") print("Loaded rows:", len(df)) print("Columns found:", list(df.columns)) # Show first 5 rows display(df.head()) # Try to detect a 'valid setup' column (several common name variants) candidates = ["ValidSetup", "validsetup", "Valid_Setup", "Valid", "valid", "ValidSetup_bool", "Valid_Setup_bool"] found = None for c in candidates: if c in df.columns: found = c break # Case-insensitive detection if exact not found if found is None: lower_map = {col.lower(): col for col in df.columns} for c in candidates: if c.lower() in lower_map: found = lower_map[c.lower()] break # Create boolean column 'ValidSetup_bool' using detected column or fallback if found is not None: print("Using column for validity:", found) series = df[found].astype(str).str.strip().str.lower() df["ValidSetup_bool"] = series.isin(["true", "1", "yes", "y", "t"]) else: print("No ValidSetup-like column found. Creating ValidSetup_bool=True for all rows (no filtering).") df["ValidSetup_bool"] = True # Quick stats total = len(df) valid_count = df["ValidSetup_bool"].sum() print(f"Total rows = {total}, ValidSetup_bool True = {valid_count}") # Create df_valid for downstream cells (the rest of notebook expects df_valid) df_valid = df[df["ValidSetup_bool"] == True].copy() print("df_valid rows:", len(df_valid)) # Display preview display(df_valid.head())

Cell 3—Compute retracement values based on the collector's schema

With a valid dataset prepared in Cell 2, the notebook now focuses on ensuring that retracement values are consistently available for analysis. In MetaTrader’s exported dataset, some of these fields may already be computed, while others need to be derived from the raw price levels. This step harmonizes the retracement calculation process.

The first action is to make sure the Range column is numerical. This column, exported from the MQL5 collector, represents the total size of the reference bar (the difference between its top and bottom). Converting it to float guarantees that subsequent mathematical operations behave as expected.

Next, the script checks whether the MetaTrader export already includes a RetracementPct column. If present, this value is interpreted as a percentage retracement (e.g., 50 means 50%) and converted into a normalized fraction between 0 and 1 by dividing by 100. This approach ensures consistency across calculations and reuses the pre-computed values when available. If no such column is found, the script falls back to computing retracement manually using the formula:

Here, Ext represents the extreme retracement level reached before the bar closed, and RefBot is the reference bar’s bottom. Dividing the distance between Ext and RefBot by the total Range gives the proportional retracement.

Since retracements should always fall between 0% and 100%, the script applies a clip operation to force all values into the [0,1] interval. This guards against anomalies caused by data irregularities or computational overshoots.

Finally, as a verification step, the notebook prints out the first few rows of key columns—RefTop, RefBot, Ext, Range, and Retracement—to confirm that the computed or imported retracement values look sensible. This preview reassures us that the pipeline is producing consistent normalized retracement measures ready for downstream statistical analysis.

# Cell 3: Compute retracement values based on the collector's schema # In our MT5 output: # - RefTop = top of the reference bar # - RefBot = bottom of the reference bar # - Ext = the extreme retracement reached before close # - RetracementPct = retracement % already computed in MT5 # 1. Use the collector's "Range" directly df_valid["Range"] = df_valid["Range"].astype(float) # 2. Use the already provided retracement percentage (if available) if "RetracementPct" in df_valid.columns: df_valid["Retracement"] = df_valid["RetracementPct"].astype(float) / 100.0 print("Using MT5-calculated RetracementPct column.") else: # fallback: compute from RefTop/RefBot and Ext df_valid["Retracement"] = (df_valid["Ext"].astype(float) - df_valid["RefBot"].astype(float)) / df_valid["Range"] print("No RetracementPct column found — computed from RefTop/RefBot/Ext.") # 3. Clip between 0 and 1 (0%–100%) df_valid["Retracement"] = df_valid["Retracement"].clip(0, 1) # Quick check print("Preview of retracement values:") display(df_valid[["RefTop","RefBot","Ext","Range","Retracement"]].head())

Figure 3. Table of values computed

Cell 4—Visual Distribution of Retracement Values

Now that retracement values have been validated and standardized, this cell takes on the task of visualizing their distribution. But before plotting, the script adds an extra safeguard: it ensures a usable Retracement column exists, regardless of which columns were included in the MetaTrader export.

The logic begins by checking whether Retracement is already present. If not, it tries to construct it. First, it looks for RetracementPct, the percentage-based retracement exported by MetaTrader 5, and converts it into a normalized 0–1 scale. If that column is unavailable, the script falls back to a custom calculation using RefTop, RefBot, Ext, and RefDir. The inclusion of RefDir (reference bar direction) makes this calculation robust because retracements must be interpreted differently for bullish and bearish reference bars:

- For a bullish bar, the retracement is measured from the RefTop down to the extreme.

- For a bearish bar, it’s measured from the RefBot up to the extreme.

If none of the required columns are available, the code raises a clear error message describing which fields are missing.

Once the retracement values are assembled, they are clipped to stay within the valid [0,1] interval, and NaN entries are dropped. If, after cleaning, no valid values remain, the script halts with an error to avoid drawing misleading plots. Otherwise, the count of usable observations is printed for transparency.

If the Seaborn library is available, the script uses sns.histplot to create a histogram overlaid with a smooth KDE curve for clarity. If it isn’t installed, a fallback is triggered using pure Matplotlib: a histogram plus a manually computed kernel density estimate (via scipy.stats.gaussian_kde). This ensures the plot looks polished even in minimal environments.

The final chart is clearly labelled with axis titles and constrained to the 0–1 range on the x-axis. It shows the overall distribution of retracement ratios across all valid setups, giving an immediate sense of how often shallow, medium, or deep retracements occur. Optionally, the figure can be saved to a PNG file sized exactly for documentation or presentation purposes.

# Plotting cell 4 (robust): ensures 'Retracement' exists and draws a 750px-wide plot import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # --- Build 'Retracement' column if needed --- if "Retracement" not in df_valid.columns: if "RetracementPct" in df_valid.columns: # MT5 already computed it as percent (0-100) df_valid["Retracement"] = pd.to_numeric(df_valid["RetracementPct"], errors="coerce") / 100.0 print("Using existing RetracementPct -> created Retracement (0-1).") else: # try to compute from RefTop/RefBot/Ext with direction awareness required = {"RefTop","RefBot","Ext","RefDir"} if required.issubset(set(df_valid.columns)): def compute_r(row): try: rng = float(row["RefTop"]) - float(row["RefBot"]) if rng == 0: return np.nan if str(row["RefDir"]).strip().lower().startswith("b") : # Bull return (float(row["RefTop"]) - float(row["Ext"])) / rng elif str(row["RefDir"]).strip().lower().startswith("be"): # Bear return (float(row["Ext"]) - float(row["RefBot"])) / rng else: return np.nan except Exception: return np.nan df_valid["Retracement"] = df_valid.apply(compute_r, axis=1).astype(float) print("Computed Retracement from RefTop/RefBot/Ext/RefDir.") else: raise KeyError("No 'Retracement' or 'RetracementPct' column, and required columns for computation are missing. " "Found columns: " + ", ".join(df_valid.columns)) # Clip to 0..1 df_valid["Retracement"] = df_valid["Retracement"].clip(lower=0.0, upper=1.0) # Drop NaNs vals = df_valid["Retracement"].dropna().values if len(vals) == 0: raise ValueError("No valid retracement values to plot after preprocessing.") print(f"Plotting {len(vals)} retracement observations (0..1 scale).") # --- Plot size: target ~750 px width --- # Use figsize such that width_inches * dpi = 750. We'll choose dpi=100, width=7.5in. fig_w, fig_h = 7.5, 4.0 fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(fig_w, fig_h), dpi=100) # Prefer seaborn if available for nice KDE overlay, otherwise fallback try: import seaborn as sns sns.histplot(vals, bins=50, stat="density", kde=True, ax=ax) except Exception: # fallback to matplotlib ax.hist(vals, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.6) # manual KDE overlay from scipy.stats import gaussian_kde kde = gaussian_kde(vals) xgrid = np.linspace(0,1,500) ax.plot(xgrid, kde(xgrid), linewidth=2) ax.set_title("Retracement Ratio Distribution") ax.set_xlabel("Retracement (0 = 0%, 1 = 100%)") ax.set_ylabel("Density") ax.set_xlim(0,1) plt.tight_layout() # Optionally save a sized PNG (uncomment to save) # plt.savefig("retracement_distribution_750px.png", dpi=100) plt.show()

Figure 4. Retracement Ratio Distribution

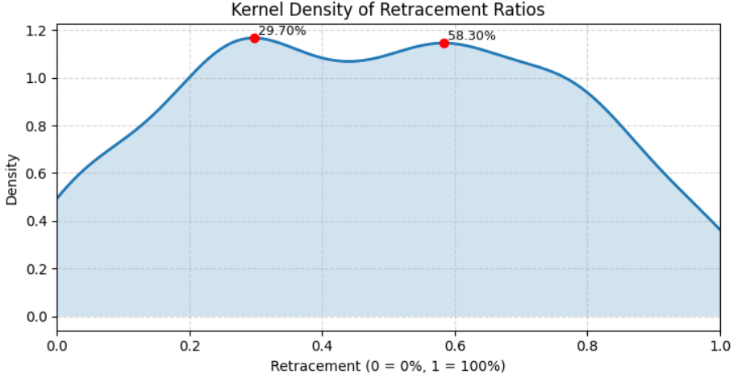

Cell 5—Kernel Density Estimation (KDE)

In this step, we move beyond basic visualization and perform a more advanced statistical analysis: Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) combined with peak detection. This approach helps reveal common retracement levels—the “hidden” zones where price often tends to stall or reverse—by analyzing the shape of the distribution rather than just raw counts in a histogram.

The script begins by ensuring that the Retracement column is available in normalized form (0–1). If missing, it rebuilds it from either the RetracementPct field or, if necessary, from RefTop, RefBot, Ext, and RefDir using the same bullish/bearish logic seen earlier. After clipping values to the valid [0,1] range and dropping NaNs, it checks that there are at least 10 valid retracement points. This safeguard prevents noisy or meaningless KDE estimates when the dataset is too small.

Next, the KDE is computed over a fine grid of 1001 points spanning 0 to 1. This high resolution allows the density curve to capture subtle structure in the data, such as multiple local maxima. To identify these maxima, the script normalizes the density curve and applies scipy.signal.find_peaks, configured to ignore tiny fluctuations by requiring a minimum prominence and spacing. The resulting peak indices correspond to retracement levels where the density function is locally strongest—effectively the “preferred” retracement levels hidden in the data.

For visualization, the KDE curve is plotted with shading beneath it, and each detected peak is highlighted with a red dot and annotated with its retracement percentage (e.g., 38.20%). Unlike the previous plotting cell, this one does not enforce a fixed pixel width, so the figure size adapts flexibly to different environments. Labels, axis ranges, and a grid are included to make the plot clean and interpretable.

Finally, the script prints a list of the detected retracement levels as percentages along with their relative prominence values, giving both a visual and numeric summary of where the strongest hidden retracement levels may lie. This combination of KDE and peak detection transforms raw retracement observations into actionable statistical insight.

# Cell 5: KDE + peak detection (robust, flexible sizing) import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt from scipy import stats from scipy.signal import find_peaks # --- ensure Retracement column exists (0..1 scale) --- if "Retracement" not in df_valid.columns: if "RetracementPct" in df_valid.columns: df_valid["Retracement"] = pd.to_numeric(df_valid["RetracementPct"], errors="coerce") / 100.0 else: required = {"RefTop","RefBot","Ext","RefDir"} if required.issubset(set(df_valid.columns)): def compute_r(row): try: rng = float(row["RefTop"]) - float(row["RefBot"]) if rng == 0: return np.nan rd = str(row["RefDir"]).strip().lower() if rd.startswith("b"): # Bull return (float(row["RefTop"]) - float(row["Ext"])) / rng elif rd.startswith("be") or rd.startswith("bear"): # Bear return (float(row["Ext"]) - float(row["RefBot"])) / rng else: return np.nan except Exception: return np.nan df_valid["Retracement"] = df_valid.apply(compute_r, axis=1).astype(float) else: raise KeyError("Cannot build 'Retracement' — missing required columns. Found: " + ", ".join(df_valid.columns)) # Clip and drop NaNs df_valid["Retracement"] = df_valid["Retracement"].clip(0,1) vals = df_valid["Retracement"].dropna().values n = len(vals) if n < 10: raise ValueError(f"Too few retracement observations to compute KDE/peaks reliably (n={n}).") # --- KDE on a fine grid --- grid = np.linspace(0, 1, 1001) # 0.001 (0.1%) resolution kde = stats.gaussian_kde(vals) dens = kde(grid) # --- peak detection on normalized density --- dens_norm = dens / dens.max() peaks_idx, props = find_peaks(dens_norm, prominence=0.02, distance=8) # tweak params as needed peak_levels = grid[peaks_idx] peak_heights = dens[peaks_idx] # --- Plot (flexible sizing, no fixed pixel restriction) --- fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 4)) # default flexible size ax.plot(grid, dens, label="KDE", linewidth=2) ax.fill_between(grid, dens, alpha=0.2) # annotate peaks for lvl, h in zip(peak_levels, peak_heights): ax.plot(lvl, h, "o", color="red") ax.text(lvl, h, f" {lvl*100:.2f}%", va="bottom", ha="left", fontsize=9) ax.set_title("Kernel Density of Retracement Ratios") ax.set_xlabel("Retracement (0 = 0%, 1 = 100%)") ax.set_ylabel("Density") ax.set_xlim(0,1) ax.grid(True, linestyle="--", alpha=0.5) plt.tight_layout() plt.show() # --- print candidate levels --- print("Candidate Hidden Retracement Levels (%):") print(np.round(peak_levels*100, 2)) print("Peak prominences (relative):", np.round(props["prominences"], 4) if "prominences" in props else "n/a")

Figure 5. Kernel Density of Retracement Ratios

Testing and Results

All the cells in the Jupyter notebook produced visual results that could be interpreted statistically. Below each cell, we presented both the code and its corresponding output, which illustrated one of the key advantages of working in Jupyter—the ability to combine computation and visualization seamlessly.

After executing the final output cell designed to save the resolved hidden values, we found that only two significant levels were detected for the H4 timeframe on the NZDUSD pair. Although this provided useful insights into the data structure, the hypothesis test did not support our expectations.

Detected peaks at (pct): [29.7 58.3] Bootstrap 200/1000... Bootstrap 400/1000... Bootstrap 600/1000... Bootstrap 800/1000... Bootstrap 1000/1000... Bootstrap done in 4.5s Peak testing results (window ±0.40%): Level 29.700% mass=9.909890e-03 p=0.4960 significant=False Level 58.300% mass=9.729858e-03 p=0.4960 significant=False Accepted (FDR<0.05) candidate levels (pct): []

The algorithm detected two candidate peaks in the data distribution, located at 29.7% and 58.3%. These peaks represent points where the algorithm initially observed local concentrations of data, suggesting potential hidden structure or repeated patterns.

To assess whether these peaks were statistically meaningful or just random fluctuations, the model performed a bootstrap test with 1000 resamples. The bootstrap process estimated how often similar peaks would appear in randomly shuffled versions of the data, giving a measure of statistical significance.

For both detected levels:

- Level 29.7% → mass = 0.0099, p = 0.4960 → Not significant

- Level 58.3% → mass = 0.0097, p = 0.4960 → Not significant

The p-values (≈0.50) indicate that these peaks occurred just as frequently in the randomized bootstrap samples as in the real data, meaning they were not statistically distinguishable from noise. Since no peak survived the false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 0.05, the algorithm concluded that there were no significant hidden levels in the dataset for the chosen timeframe (H4 on NZDUSD).

Backtesting strategies with discovered levels

In MetaTrader 5, I experimented by adding two custom retracement levels to the default Fibonacci set: 29.7% and 58.3%. From our Jupyter analysis, both levels produced results of mass = 0.0099, p = 0.4960 and mass = 0.0097, p = 0.4960 respectively, which were not statistically significant. However, when plotted on charts, one of these levels appeared to have been respected by price action in the past. This suggests that, while the statistical test did not confirm significance, there may still be practical relevance worth exploring.

Currently, these levels were added manually, but future work could involve programmatically integrating such values into MetaTrader 5 for automated testing across multiple pairs and timeframes. See Figure 6 below for an illustration.

Figure 6. New Levels Resolved

Conclusion

This project was driven by ambition and curiosity—from chart-based observations of price action within the Fibonacci retracement framework, to recognizing irregularities in how price interacts with known levels, and even questioning whether hidden levels might exist between the traditional retracement points. To explore these ideas, we combined MQL5 for automated data collection with Python inside the Jupyter interactive web environment, which provided powerful tools for data analysis, visualization, and multi-language integration.

While we successfully produced preliminary results, some challenges emerged. Our dataset was limited, and the manual application of calculated retracement values onto charts showed promise but did not align with our initial hypotheses. This suggests that both our data collection process and swing/retracement detection methods may need refinement. Expanding the analysis to cover multiple currency pairs and timeframes, as well as re-engineering detection algorithms, would likely improve accuracy and reliability.

Despite these setbacks, the foundation we have laid is valuable. It demonstrates how MQL5 and Python can be combined for quantitative trading research, serving as a practical starting point for beginners who want to bridge trading platform automation with data science. Although the initial results did not fully support our expectations, the charts continue to reveal interesting possibilities worth further investigation. With more robust testing and refined methods, this line of research could still uncover insights into hidden retracement dynamics.

Unlike relying on guesswork to add custom retracement levels, this approach leverages data science together with the available MQL5 tools to bring efficiency and structure to the process. Below is a table with the attached resources. You are welcome to go through the sources and experiment to share your thoughts for further discussion. Until the next publication, stay tuned.

Attachments

| File Name | Version | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CandleRangeData.mq5 | 1.0 | MQL5 script that collects candle range and retracement data from MetaTrader 5 charts and exports it into CSV format for analysis. |

| HiddenFiboLevels.ipynb | N/A | Jupyter Notebook containing Python code for loading the exported CSV, cleaning the data, testing potential hidden Fibonacci retracement levels, and visualizing results. |

| CandleRangeData_NZDUSD_H4.csv | N/A | Sample dataset generated by the MQL5 script for the NZDUSD currency pair on the H4 timeframe, used as input for Python analysis. |

Warning: All rights to these materials are reserved by MetaQuotes Ltd. Copying or reprinting of these materials in whole or in part is prohibited.

This article was written by a user of the site and reflects their personal views. MetaQuotes Ltd is not responsible for the accuracy of the information presented, nor for any consequences resulting from the use of the solutions, strategies or recommendations described.

Neural Networks in Trading: Models Using Wavelet Transform and Multi-Task Attention

Neural Networks in Trading: Models Using Wavelet Transform and Multi-Task Attention

Post-Factum trading analysis: Selecting trailing stops and new stop levels in the strategy tester

Post-Factum trading analysis: Selecting trailing stops and new stop levels in the strategy tester

Evolutionary trading algorithm with reinforcement learning and extinction of feeble individuals (ETARE)

Evolutionary trading algorithm with reinforcement learning and extinction of feeble individuals (ETARE)

Market Simulation (Part 02): Cross Orders (II)

Market Simulation (Part 02): Cross Orders (II)

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use