MQL5 Wizard Techniques you should know (Part 85): Using Patterns of Stochastic-Oscillator and the FrAMA with Beta VAE Inference Learning

Introduction

Within MetaTrader 5’s ecosystem, the MQL5 Wizard does stand as a solid tool that enables traders to rapidly prototype and deploy new trade ideas. As we have covered in past articles, this all happens without getting into low-level coding. At its core, the wizard utilizes a modular framework that allows traders to choose from predefined signal classes, or money management strategies, or trailing stop mechanisms. The ability to have a plug and play approach in assembling an Expert Advisor has the unintended consequence of democratizing algorithmic trading, which makes trading more accessible to individuals with varying level of expertise, and this should have the long term effect of boosting market liquidity, all else being equal.

For part-85, of these series, we are delving into an extended application of the wizard, as we have in some of the past articles, by integrating machine learning. Specifically, we are looking at the Beta-Variational Auto-Encoder algorithm of an inference model, that we had considered in a recent article, but that we now use to process the binary encoded signals of the indicator-pair of our last article. To recap, the beta-VAE is applied as an unsupervised learning model that compresses high-dimensional input data into a latent space. By doing so, it captures underlying structures and relationships that traditional rule-based systems could overlook. This automation process, on paper, is meant to not only improve pattern recognition but also support inference-based making of decisions within our custom signal classes.

We are using the indicator-pairing of our last installment, part-84, where we as usual considered 10 key, distinct patterns that we indexed from 0 to 9 having been derived from the Stochastic Oscillator and the Fractal Adaptive Moving Average. We noted varying performance across these 10 patterns in the walk-forward tests we made. Patterns from 0 to 4 as well as those from 7 to 8 showed some robustness by being profitable across our scope of assets that had been chosen to capitalize on different market regimes. Nonetheless, patterns 5, 6 and 9 lagged majorly, failing to show profitability in the out-of-sample forward walk period.

It is worth re-emphasizing that our test window is very limited, therefore these results at best should be taken as a clue on what patterns need further-testing, not which patterns are dependable. The underperformer patterns were defined as flat FrAMA with Stochastic crossovers for pattern-5, overbought/oversold Stochastic hooks with sloping FrAMA for pattern-6, and extreme Stochastic-Oscillator levels with opposing FrAMA slopes for pattern-9.

These failures could be attributed to limitations of the inflexibility of these patterns. Or it could be that testing scope was too restrictive, and it is these patterns and not some of our ‘profitable’ ones above that are resilient in the long term. This debate can best be settled by the reader from independent testing. For our purposes, though, we look into how machine learning could, if at all, rehabilitate the fortunes of patterns 5, 6, and 9.

Buy signal (Pattern 5): Flat FrAMA + Stoch cross up under 30

Sell signal (Pattern 6): Stoch “M” peak above 80 + FrAMA slope up

Sell signal (Pattern 9): Upward FrAMA + Stoch > 90 and falling

The thesis for this article posits that the beta-VAE is able to transform binary indicator values, composed as vectors, into meaningful latent representations. Because we emphasize disentangled features thanks to the beta-parameter, that aims to balance reconstruction accuracy and latent regularization, the model is able to uncover hidden trading patterns and structures. We are able to show this by training on historical data for XAU USD, SPX 500, and USD JPY. Post training, we export our model via ONNX to a custom MQL5 signal class for assembly with the MQL5 Wizard. Our forward walk results did indicate modest forward-walk gains for the asset XAU USD, which in a sense underscores the potential of inference learning in fine-tuning some underperforming raw signal patterns.

Pattern Detection

For machine learning models used in forecasting, and not say pattern recognition, vectorized continuous inputs, that can include normalized price or indicator values, are usually the beginning step towards machine learning integration. They permit large arrays of time-series data to flow into the model without manual branching. This lets the algorithms infer relationships among Stochastic oscillations and FrAMA’s form as well as price action volatility, all autonomously.

This structure is able to scale naturally because once the indicator vectors are aligned and windowed, in python several bars can get processed concurrently, within a few milliseconds. When exporting to MQL5, strategy tester’s ‘on-new-bar’ methods do not yield a similar performance. However, with this approach we would not need if clauses to decide for instance if the Stochastic K crossed above the D or if the FrAMA is flattening, etc. All this information is captured within the floating-point tensors. For systems that are trained on GPUs these tensors provide elegant compact storage not just with buffering the inputs but more importantly in storing training deltas which prevents continuous calculations of these output - target differences.

Nonetheless, the elegance poses some fragility. The continuous nature of these input vectors implies they are never pure, in that they carry market noise, indicator lag, and rounding artifacts that tend to mimic false correlations. In this context, even just one mis-scaled feature can shift the mean, corrupt training gradients and result in an illusory precision. In cases where the input data is captured in volatile regimes, the model can learn fluctuations that seem predictive in training, but turn useless in live trading. More than this, continuous signals can blur logical boundaries - a K of 69.8 and 70.1 may flip classification without meaningful changes in the trend. Using continuous input data, as we have highlighted in recent articles, can give systems that perform well in simulation and yet waver when market regimes change because floating-point smoothness musks discrete market behavior. The model, as some say, would be ‘hallucinating’, such as by indicating forecasts even with random data.

A pragmatic ‘middle-path’, that we explore in this article and have recommended in the past, is distilling the floating-point input data into boolean/binary vectors which act like fingerprints for specific events. Rather than feeding the model exhaustive numerical ranges, we translate patterns such as a cross up of the Stochastic buffers or a flattening of the FrAMA into a 1 when present, or a 0 when absent. Every bit in the surmised vector of these values, therefore, represents a well-defined condition, already verified by a small ‘if’ clause that was included in the preprocessing functions. A low-dimensioned, and arguably noise-resistant input gets forged by these binary patterns, and it puts emphasis on structure over magnitude. Underlying relationships between event combinations can be learnt by the beta-VAE model, as opposed to fluctuating values. Compressing these into a latent space, then, makes a case for reflecting market modes more reliably.

Therefore, whereas vectorized continuous data gives us the scale and performance to compute, since we totally bypass if clauses, binary vectorization brings clarity to the decisions. It is able to convert raw numeric ‘chaos’ into a form of ‘symbolic-order’ with each 1 or 0 encoding meaning. Also, inference will depend not just on fragile thresholds, but also on the already coded logic of crucial ‘if’ clauses.

Stochastic-Oscillator’s drawbacks

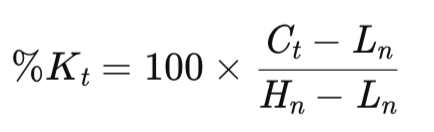

This oscillator, developed by George Lane, is inherently momentum based. It puts a metric on the closing price’s position in comparison to its recent range, thus pointing out the likelihood of reversal. To recap, this is worked out, for the main K buffer as:

Where:

- Ct = current close,

- Hn = highest high over the past n periods,

- Ln = lowest low over the past n periods,

Our look back period, n, often defaults to 20, however we left this value as a tunable hyperparameter in the last 2 articles where we introduced this indicator pairing. This is not necessarily best practice because it can lead to curve fitting. However, the used look back period does get smoothed over ‘m’ periods. This m often defaults to 3, which we have maintained for our purposes. The smoothing gives us refined or less volatile K. The D buffer, as we covered in part-83, lags the K as a smoothed moving average, also over a period of 3 by default which we have maintained. It serves to pinpoint peaks in the K buffer with the help of crossovers. We use this indicator as from the inbuilt class of ‘CiStochastic’, and like all stochastic oscillators it outputs values in the 0–100 range, with the levels of 80 and 20 serving as key thresholds.

Even though it is a very simple indicator, this indicator can display major weaknesses. When markets are in a trend, it has habits of lagging, a lot. For instance, if these trends are bullish, the K buffer values can ‘hug’ the upper levels, that are 80 and above, for an extended period, in spite of crossovers that get reversed within this band, without crossing down to lower levels. This generates persistent false sell signals as the momentum continues to persist. On the flip side, downtrends pin the K buffer to the sub 20 level, which in effect ‘delays buying cues’ because again we end up with a broken clock syndrome where many false signals are generated before finally being right.

This lag could be attributed to the range-based formula that normalizes the close price against its extreme values but ignores the trend persistence. This results in ‘stuck-readings’. Our python implementation of this is able to capture the K and D buffers as vectorized series. We implemented a custom class ‘SignalFrAMAStochastic’ with functions like ‘cross-up-series’ where the shifts spot bar on bar changes. Nonetheless, real world market noise from live testing tends to amplify the noise of false crossovers when the markets are trending. We implement this in python as follows;

def Stochastic( df: pd.DataFrame, k_period: int = 20, d_period: int = 3, smooth_k: int = 3, source_col: str = "close", only_stochastic: bool = False ) -> pd.DataFrame: """ Compute Stochastic Oscillator (%K and %D) and append columns to the DataFrame. Parameters ---------- df : pd.DataFrame Input DataFrame; must include columns 'high', 'low', and the `source_col` (default 'close'). k_period : int Lookback period for %K (highest high / lowest low). Default 14. d_period : int Period for %D (moving average of %K). Default 3. smooth_k : int Smoothing window applied to raw %K before computing %D. Default 3. source_col : str Price column to use for close values (default 'close'). only_stochastic : bool If True, return only the Stochastic columns. Returns ------- pd.DataFrame DataFrame with appended columns: 'Stoch_%K', 'Stoch_%K_smooth', 'Stoch_%D' """ required_cols = {"high", "low", source_col} if not required_cols.issubset(df.columns): raise ValueError(f"DataFrame must contain columns: {required_cols}") if not all(isinstance(p, int) and p > 0 for p in (k_period, d_period, smooth_k)): raise ValueError("k_period, d_period, and smooth_k must be positive integers") out = df.copy() low_k = out["low"].rolling(window=k_period, min_periods=k_period).min() high_k = out["high"].rolling(window=k_period, min_periods=k_period).max() # Raw %K (0-100) raw_k = (out[source_col] - low_k) / (high_k - low_k) raw_k = raw_k * 100.0 # Smoothed %K (optional smoothing) stoch_k = raw_k.rolling(window=smooth_k, min_periods=smooth_k).mean() # %D is SMA of smoothed %K stoch_d = stoch_k.rolling(window=d_period, min_periods=d_period).mean() out['raw_k'] = raw_k out["k"] = stoch_k out["d"] = stoch_d if only_stochastic: return out[["raw_k", "k", "d"]].copy() return out

class SignalFrAMAStochastic: # constructor unchanged — can accept pandas Series too def __init__( self, frama: Sequence[float], close: Sequence[float], high: Sequence[float], low: Sequence[float], k: Sequence[float], # Stochastic %K series pips: float, point: float, past: int, x_index: int = 0 ): # store as pandas.Series if possible to help with vectorized operations if isinstance(frama, pd.Series): self.frama = frama else: self.frama = pd.Series(frama) if isinstance(close, pd.Series): self.close = close else: self.close = pd.Series(close) if isinstance(high, pd.Series): self.high = high else: self.high = pd.Series(high) if isinstance(low, pd.Series): self.low = low else: self.low = pd.Series(low) if isinstance(k, pd.Series): self.k = k else: self.k = pd.Series(k) self.m_pips = pips self.point = point self.m_past = past self._x = x_index # ------------------------ # Small helpers (vectorized) # ------------------------ @staticmethod def cross_up_series(a: pd.Series, b: pd.Series) -> pd.Series: """ Vectorized CrossUp: True where a crossed up b between previous and current bar. Equivalent MQL: (a1 <= b1) && (a0 > b0) In pandas chronological order: a.shift(1) = previous a, a = current a """ a_prev = a.shift(1) b_prev = b.shift(1) return (a_prev <= b_prev) & (a > b) # Trimmed code... # ------------------------ # Vectorized divergence detection # ------------------------ def bullish_divergence_series(self) -> pd.Series: """ Vectorized detection of bullish divergence: - Find local lows (low < low.shift(1) & low < low.shift(-1)) - For consecutive pairs of local lows (older -> newer), mark the time of the *second* low True when: low_old < low_new (price makes lower low) K_old > K_new (oscillator makes higher low) This mirrors the MQL routine that finds two local lows within a lookback and checks them. """ low = self.low k = self.k # boolean mask of local minima is_local_min = (low < low.shift(1)) & (low < low.shift(-1)) local_idx = np.flatnonzero(is_local_min.to_numpy(copy=False)) # prepare result array res = np.zeros(len(low), dtype=bool) # We will iterate adjacent pairs of local extrema (sparse). # Only consider pairs where the two minima are not more than (m_past+? ) apart is optional; # Here we mimic original by not imposing an explicit global window; user can post-filter if needed. for i in range(1, len(local_idx)): older = local_idx[i - 1] newer = local_idx[i] # compare values (note: these are numpy indices; preserve pandas indexing by assigning by position) if low.iat[older] < low.iat[newer] and k.iat[older] > k.iat[newer]: # mark the time of the newer local low res[newer] = True return pd.Series(res, index=low.index) def bearish_divergence_series(self) -> pd.Series: """ Vectorized detection of bearish divergence: - Find local highs (high > high.shift(1) & high > high.shift(-1)) - For consecutive pairs of local highs (older -> newer), mark the time of the *second* high True when: high_old > high_new (price makes higher high) K_old < K_new (oscillator makes lower high) """ high = self.high k = self.k is_local_max = (high > high.shift(1)) & (high > high.shift(-1)) local_idx = np.flatnonzero(is_local_max.to_numpy(copy=False)) res = np.zeros(len(high), dtype=bool) for i in range(1, len(local_idx)): older = local_idx[i - 1] newer = local_idx[i] if high.iat[older] > high.iat[newer] and k.iat[older] < k.iat[newer]: res[newer] = True return pd.Series(res, index=high.index) # ------------------------ # Convenience wrappers for CrossUp/Down using stored Series # ------------------------ def cross_up(self, a_col: pd.Series, b_col: pd.Series) -> pd.Series: return self.cross_up_series(a_col, b_col) def cross_down(self, a_col: pd.Series, b_col: pd.Series) -> pd.Series: return self.cross_down_series(a_col, b_col)

This indicator’s performance can also diverge starkly across different market regimes. In mean-reverting settings, for instance, when the forex pair USD JPY is in low volatility phase, the stochastic can shine since oversold bounces and overbought fades are frequent and tend to align well with equilibrium pulls. However, in momentum driven setups that can include the rarified breakouts of XAU USD, it is bound to falter a lot by mistaking acceleration for reversals. Back tests in the last article did indicate patterns 5 and 9 depending a lot on the extreme levels of sub 10 and post 90. The crosses were underperforming and the unprofitable forward walks that we got can be pinned on regime mismatches, we were trending and not ranging. The SPX 500’s bullishness this year, especially from the April lows, exacerbated this, given that the Stochastic Oscillator’s sensitivity to market noise in the short term can result in it ignoring broader market impulses.

In order to remedy these flaws, the FrAMA’s contextual filter is crucial. Our adaptive average indicator, that uses fractal dimension-based alpha, changes its smoothing to match the market structure. The averaging period is lowered when trends are smooth, and it is elevated when markets are choppy to capture the broader market drive. By overlaying FrAMA’s slope or its flatness, we make the stochastic signals, like validating pattern-5, make crosses only when the FrAMA is flat. We essentially filter volatility induced noise. This symbiotic relationship shapes the inputs to the beta-VAE model, where the binary flag encode interactions that are ‘regime-aware’ which in turn allows learning that is latent, a disentanglement of the lag between true edges, which on paper should make Expert Advisor’s more resilient.

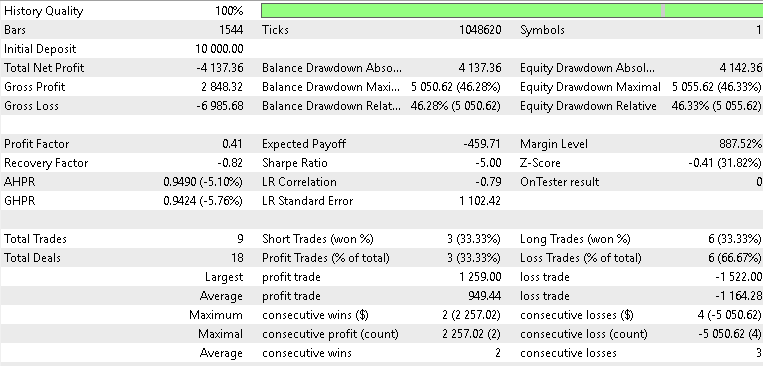

FrAMA in Python

Our adaptive moving average give us a paradigm shift from smoothing that is static to the kind that is dynamic and therefore more responsive. This indicator draws from the chaos theory, by incorporating the fractal dimension, to put a number on the volume of market noise versus market structure. So, for a window of n bars, the typical default is also 20 like the stochastic, but FrAMA does bisect this period into two. This allows computing range ratios N1 and N2 across sub-windows, as well as N(1+2) for the complete window. To recap from our earlier article, D is defined as:

Where N1 and N2 are the afore mentioned range ratios. Its values are clamped between 1 for a smooth trend and 2 as an indicator of only noise. Alpha the adaptive weight is also bounded from 0.01 to 1.0, and we use this with the price averaging buffers to output an adaptive average as already highlighted in previous articles, specifically the article before the last which as of this writing is still pending to be published. In MQL5 we implemented it, overlooked all these formula intricacies, by using the ‘CiFrAMA’ inbuilt indicator class. With python, though, our approach is as follows:

def FrAMA( df: pd.DataFrame, period: int = 20, price_col: str = "close", min_alpha: float = 0.01, max_alpha: float = 1.0, only_frama: bool = False ) -> pd.DataFrame: """ Compute Fractal Adaptive Moving Average (FRAMA) per John Ehlers' formulation. Parameters ---------- df : pd.DataFrame Input DataFrame; must include 'high', 'low', and price_col (default 'close'). period : int Window length used to compute fractal dimension (commonly 16). Must be >= 4. price_col : str Column name to use as price (commonly 'close'). min_alpha : float Minimum alpha clamp (commonly 0.01). max_alpha : float Maximum alpha clamp (commonly 1.0). only_frama : bool If True, return only the FRAMA column. Returns ------- pd.DataFrame DataFrame with appended column: 'FRAMA' """ required_cols = {"high", "low", price_col} if not required_cols.issubset(df.columns): raise ValueError(f"DataFrame must contain columns: {required_cols}") if not (isinstance(period, int) and period >= 4): raise ValueError("period must be an integer >= 4") if not (0.0 < min_alpha <= max_alpha <= 1.0): raise ValueError("min_alpha and max_alpha must satisfy 0 < min_alpha <= max_alpha <= 1") out = df.copy() n = period half = n // 2 price = out[price_col].to_numpy(dtype=float) high = out["high"].to_numpy(dtype=float) low = out["low"].to_numpy(dtype=float) length = len(out) frama = np.full(length, np.nan, dtype=float) # Seed: before we have enough bars, set FRAMA to price (common practice) # We'll start the loop at index 0 and set initial FRAMA to price[0]. if length == 0: out["frama"] = frama return out if not only_frama else out[["frama"]].copy() frama[0] = price[0] # iterate; we need at least 'n' bars to compute a fractal dimension for i in range(1, length): if i < n: # not enough history to compute full fractal measure -> fallback to price frama[i] = price[i] continue start = i - n + 1 # first half window: start .. start+half-1 fh_start = start fh_end = start + half - 1 # second half window: start+half .. i sh_start = fh_end + 1 sh_end = i # compute ranges per sub-window (using highs and lows) mH = np.max(high[fh_start: fh_end + 1]) # max high in first half mL = np.min(low[fh_start: fh_end + 1]) # min low in first half N1 = (mH - mL) / float(max(1, half)) HH = np.max(high[sh_start: sh_end + 1]) # max high in second half LL = np.min(low[sh_start: sh_end + 1]) # min low in second half N2 = (HH - LL) / float(max(1, half)) # entire window: Mx = np.max(high[start: i + 1]) Mn = np.min(low[start: i + 1]) N3 = (Mx - Mn) / float(max(1, n)) # compute fractal dimension D according to Ehlers: # D = (log(N1 + N2) - log(N3)) / log(2) # Use guard clauses when N1, N2, N3 are zero or negative if (N1 > 0.0) and (N2 > 0.0) and (N3 > 0.0): D = (np.log(N1 + N2) - np.log(N3)) / np.log(2.0) else: # fallback to D = 1 (line-like) when not computable D = 1.0 # alpha conversion using Ehlers' exponential mapping (clamped) alpha = np.exp(-4.6 * (D - 1.0)) if alpha < min_alpha: alpha = min_alpha if alpha > max_alpha: alpha = max_alpha # EMA-like update frama[i] = alpha * price[i] + (1.0 - alpha) * frama[i - 1] out["frama"] = frama if only_frama: return out[["frama"]].copy() return out

The core strength of FrAMA can arguably be put to its chameleon like adaptability to a trend. In trends that are efficient, where D is low and alpha shrinks towards 0.01, FrAMA copies a long-period Simple Moving Average, a form of lag-reduced following. On the flip side, in fractal chaos as D gets to its highs, alpha would approach 1.0 and in essence the FrAMA would behave like a rapid EMA that hugs price to evade whipsaws. This tends to outperform moving averages with fixed look back periods in cases where there is a regime shift. Case in point, if we focus on XAU USD’s volatile spike’s this year as gold started its bull run, FrAMA’s high alpha values make it more responsive and would easily deal with the stochastic’s lagging, or broken clock syndrome we highlighted above. We implement this in python as follows

class SignalFrAMAStochastic: # constructor unchanged — can accept pandas Series too def __init__( self, frama: Sequence[float], close: Sequence[float], high: Sequence[float], low: Sequence[float], k: Sequence[float], # Stochastic %K series pips: float, point: float, past: int, x_index: int = 0 ): # store as pandas.Series if possible to help with vectorized operations if isinstance(frama, pd.Series): self.frama = frama else: self.frama = pd.Series(frama) if isinstance(close, pd.Series): self.close = close else: self.close = pd.Series(close) if isinstance(high, pd.Series): self.high = high else: self.high = pd.Series(high) if isinstance(low, pd.Series): self.low = low else: self.low = pd.Series(low) if isinstance(k, pd.Series): self.k = k else: self.k = pd.Series(k) self.m_pips = pips self.point = point self.m_past = past self._x = x_index # Trimmed Code... @staticmethod def frama_slope_series(frama: pd.Series) -> pd.Series: """ Vectorized FrAMASlope: FrAMA(t) - FrAMA(t-1) (maps MQL FrAMA(ind) - FrAMA(ind+1)) Note: first value will be NaN because shift(1) yields NaN at the start. """ return frama - frama.shift(1) def flat_frama_series(self, window: Optional[int] = None) -> pd.Series: """ Return boolean Series: True where absolute FRAMA slope stayed <= tol for `window` bars including current bar and previous (window-1) bars. - window default: self.m_past - tol = self.m_pips * self.point """ if window is None: window = self.m_past tol = self.m_pips * self.point slope = self.frama_slope_series(self.frama).abs() # rolling max over the last `window` bars (includes current and previous window-1) # need min_periods=window to mimic MQL conservative behavior rolling_max = slope.rolling(window=window, min_periods=window).max() return rolling_max <= tol def far_above_series(self, mult: float) -> pd.Series: """ Vectorized FarAboveFrama for every row: dist = abs(close - frama) atr = high.shift(1) - low.shift(1) (previous bar's range, matching MQL's ind+1) condition: close > frama AND dist > mult * point * atr / 4 """ dist = (self.close - self.frama).abs() atr = (self.high.shift(1) - self.low.shift(1)) # avoid divide-by-zero; treat atr<=0 as False cond = (self.close > self.frama) & (atr > 0) & (dist > (mult * self.point * atr / 4.0)) # fill NaNs with False return cond.fillna(False) def far_below_series(self, mult: float) -> pd.Series: """ Vectorized FarBelowFrama for every row: condition: close < frama AND dist > mult * point * atr / 4 """ dist = (self.close - self.frama).abs() atr = (self.high.shift(1) - self.low.shift(1)) cond = (self.close < self.frama) & (atr > 0) & (dist > (mult * self.point * atr / 4.0)) return cond.fillna(False) # ------------------------ # Vectorized divergence detection # ------------------------ # Trimmed code...

Within the signal patterns that we have been referring to in the last articles and inherently in this one, the utility functions ‘flat_frama_series’, and ‘frama_slope_series’ help identify ranges for pattern 5, as well as slopes for pattern 9 respectively.

Market Archetypes

Exhibited behaviors by markets can be classified into a diverse array of taxonomies. For the last 2 articles and this one, we have, in principle, focused on just three. Trending vs Mean-Reverting; Autocorrelated vs Decoupled; and High-Volatility vs Low Volatility. Market regimes that are trending can feature persistent directional moves that can have indicators like the FrAMA’s positive slope being a dominant feature, thus aligning with plays for momentum, but not accounting for false reversal signals from the stochastic. On the flip side, mean-reverting market phases fluctuate about an equilibrium point and this does favor the stochastic oscillator’s overbought/oversold bounces, especially if the FrAMA is essentially flat.

Correlations track asset interdependence, for instance there is a lot of chatter on the eerie correlation between equities and supposed hedges like Bitcoin. The two are moving in tandem a lot, contrary to the academic argument of Bitcoin being a hedge against US economy and ‘fiscal-irresponsibility’. If the two were truly decoupled, then holding both would amount to an effective form of diversification. Within the SPX 500, occasionally there are included sectors that could have negative correlations, and these changes formed the argument for our using this asset in the last articles for the auto-correlation patterns of 2, 3, and 9.

This diversity in market types makes the case for a ‘broad-testing-universe’ to test and validate our beta-VAE’s pattern learning. We argued that these market types were each suited for particular assets, and so we chose three assets each from an established asset class. We picked XAU USD, SPX 500, and USD JPY. Gold was picked from the commodities' basket, and it embodies to a large extent commodities’ volatility that is usually driven by flows of safe-havens, or geopolitical tensions, inflation high volatility etc. Its memory effects, that can be prolonged, do test the beta-VAE’s latent capture of regime persistence.

SPX 500 was chosen as an established proxy to what is happening in the equities space. It exhibits a correlated trend following nature depending on the risk sentiment. It helped expose stochastic-lags in momentum phases, which was when pattern-9 faltered. Finally, USD JPY was the representative from the forex space, and it was meant to exploit volatility plays within the markets as affected by yield differentials and central bank interventions. This selection served to probe ‘flat-FrAMA’ filters, particularly in pattern-5.

For our VAE model, we implement the three laggard patterns concurrently, by developing a latent model that captures or learns the underlying patterns across the signal patterns 5, 6, and 9. We still test each asset independently, with each tested asset concurrently examining the three laggard patterns. Multi pattern testing can be problematic when we are not aggregating their signals properly, such as with the machine learning approach we are using in this article. We have mentioned the dangers of different patterns cancelling each other's positions in prior articles, such that any training often amounts to a curve fitting exercise. With the approach we have here, all signals unify and generate long/short calls as one. Not independently, so this combination of the patterns to a beta-VAE model could be a case of the sum being greater than the parts.

The beta-VAE Model

At the core of our signal-umbrella model is the beta Variational Auto Encoder, a generative model that is unsupervised, that is an upgrade to the standard VAE by focusing on disentangled representations. Its structure is set as comprising an encoder-decoder pair with a hidden space that is usually highly dimensional, a magnitude more than the input. The encoder, is a neural network that serves as a feedforward from a low dim input space to a high dimensioned latent space.

For this article, our input is 6 dimensioned to a 2048 dimensioned latent space. The 6 input dimensions are for the 3 signal patterns 5, 6, and 9 and to recap every pattern outputs a 2 dimensioned vector where every index is normalized to output a value 1 or 0. The two indices each track bullishness and bearishness of a given signal pattern. We implement the beta-VAE model in python as follows:

# ----------------------------- β-VAE (inference simplified to VAE-only) ----------------------------- class BetaVAEUnsupervised(nn.Module): """ Encoder: features -> (mu, logvar) Decoder: z -> x_hat **Inference (now VAE-only):** latent z is mapped to y via an internal head. All former infer modes (ridge/knn/kernel/lwlr/mlp) are bypassed. """ def __init__(self, feature_dim, latent_dim, k_neighbors=5, beta=4.0, recon='bce', infer_mode='vae', ridge_alpha=1e-2, kernel_bandwidth=1.0): super().__init__() self.latent_dim = latent_dim self.k_neighbors = k_neighbors self.beta = beta self.recon = recon self.infer_mode = 'vae' # force VAE-only self.ridge_alpha = float(ridge_alpha) self.kernel_bandwidth = float(kernel_bandwidth) # Encoder self.feature_encoder = nn.Sequential( nn.Linear(feature_dim, 256), nn.ReLU(), nn.Linear(256, 128), nn.ReLU(), nn.Linear(128, latent_dim * 2) ) # Decoder self.decoder = nn.Sequential( nn.Linear(latent_dim, 128), nn.ReLU(), nn.Linear(128, 256), nn.ReLU(), nn.Linear(256, feature_dim) ) # New: latent→y head (supervised head trained with MSE) self.y_head = nn.Sequential( nn.Linear(latent_dim, 128), nn.ReLU(), nn.Linear(128, 1) ) def encode(self, features): h = self.feature_encoder(features) z_mean, z_logvar = torch.chunk(h, 2, dim=1) return z_mean, z_logvar def reparameterize(self, mean, logvar): std = torch.exp(0.5 * logvar) eps = torch.randn_like(std) return mean + eps * std def decode(self, z): return self.decoder(z) def predict_from_latent(self, z): # VAE-only mapping return self.y_head(z) def forward(self, features, y=None): mu, logvar = self.encode(features) z = self.reparameterize(mu, logvar) x_logits = self.decode(z) y_hat = self.predict_from_latent(z) if y is not None: return {'z': z, 'z_mean': mu, 'z_logvar': logvar, 'x_logits': x_logits, 'y_hat': y_hat} else: return {'y': y_hat}

The mapping of the 6D binary input to a 2048D latent layer happens via linear ReLU layers in the configuration 6⇾256⇾128⇾4096. We have, 4096 at the end because it represents two sets of 2048. We have a split with one branching to the mean and another to a logarithm of the variance, each sized 2048. Re-parameterization is used by this probabilistic encoding to sample for z, the regenerated input and this then feeds into the network output which then allows backpropagation to be done. The decoding happens in reverse to the stated configuration by being in the order 2048⇾128⇾256⇾6. This reconstruction of the binary input provides logits, which then undergo sigmoid activation to produce probabilities.

In a recent prior beta-VAE implementation we solely relied in the dual mode of a ‘forward-pass’ to infer forecast price action since on training it had been paired with indicator input values. The fed input data to make this forecast would then have the sought, future price changes, given neutral placeholder values. Since our range, then, for price changes was from 0.0 to 1.0, the neutral placeholder value was 0.5. Our implemented beta-VAE has a similar flexible forward pass function, however we have added a novel latent to y head size configured as 2048⇾128⇾1, and this forecasts the next price action as values in the range -1 to +1, implying bearing to bullish respectively. This is from z as the input, and it effectively means we are blending unsupervised learning with supervised learning.

The beta parameter that we use in this VAE sets how strongly a model enforces simplicity and independence of the variables in its hidden space, aka the latent space. In an Autoencoder that is ‘variational’, two things need to be balanced. The reconstruction accuracy of the input data and the regularization or a measure of how closely the latent space matches a well established metric system, such as a standard normal distribution.

When beta is 1, this is referred to as a ‘normal’ VAE. The name, as one would guess, comes from the normal distribution and in this instance the Kullback-Leibler divergence would adjust the values in the latent space such that they roughly follow a Gaussian distribution. However, once we start to increase beta and for instance set it at 4, we begin to allocate more importance or ‘weight’ to the regularization. What would essentially be happening would be a push to have the values in the latent space as sparse as possible, with many close to zero, plus a lot of independence and fewer correlations. The purpose of this, in practice, is that it helps the model better separate and ‘disentangle’ the various hidden features and patterns in the latent space.

A better distinguished hidden space is supposed to help the VAE generalize and better identify patterns in out of sample situations. Our beta-VAE-Loss function is meat to work out the Kullback-Leibler and we implement it in python as follows:

def beta_vae_loss(features, x_logits, mu, logvar, beta=4.0, recon='bce'): if recon == 'bce': recon_loss = F.binary_cross_entropy_with_logits(x_logits, features, reduction='sum') / features.size(0) else: recon_loss = F.mse_loss(torch.sigmoid(x_logits), features, reduction='mean') * features.size(1) kl = -0.5 * torch.sum(1 + logvar - mu.pow(2) - logvar.exp()) / features.size(0) loss = recon_loss + beta * kl return loss, recon_loss.detach(), kl.detach()

KL is computed as -0.5 ∑(1 + logvar - μ² - exp(logvar)) and then averaged per batch, then weighted by beta. This, as argued above, swaps reconstruction accuracy for latent space variability, revealing hidden indicator hierarchies. The loss decomposition is a multistep process, where we can reconstruct the input data using binary cross entropy with logits. The total loss is a hybrid objective that guarantees the model is not only able to reconstruct input patterns, but that the latent space is able to ‘specialize’ and capture different facets of the input feature data, where for instance some values log crossover strength, others slope direction etc. The ability to log a diversity of these features, again being controlled by the beta factor, as we have argued above.

MQL5 Implementation

In order to bridge python’s machine learning ecosystem with MQL5’s trading framework, we cover key steps in python that lead up to exporting an ONNX file for use in MQL5. These steps, as covered above, amount to creating a seamless pipeline for data handling, model training, and deployment. We initialize the exported ONNX models, one for each asset, recall each model uses all the three patterns synergistically without cross order clashes. Whereas in past articles, ONNX models were pattern specific, these here are asset specific. Our class constructor and validation therefore shapes up as follows:

//+------------------------------------------------------------------+ //| Constructor | //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ CSignalIL_Stochastic_FrAMA::CSignalIL_Stochastic_FrAMA(void) : m_pattern_6(50), m_pattern_9(50), m_pattern_5(50), m_model_type(0) //m_patterns_usage(255) { //--- initialization of protected data m_used_series = USE_SERIES_CLOSE + USE_SERIES_TIME; PatternsUsage(m_patterns_usage); //--- create model from static buffer m_handles[0] = OnnxCreateFromBuffer(__84_USDJPY, ONNX_DEFAULT); m_handles[1] = OnnxCreateFromBuffer(__84_XAU, ONNX_DEFAULT); m_handles[2] = OnnxCreateFromBuffer(__84_SPY, ONNX_DEFAULT); }

//+------------------------------------------------------------------+ //| Validation settings protected data. | //+------------------------------------------------------------------+ bool CSignalIL_Stochastic_FrAMA::ValidationSettings(void) { //--- validation settings of additional filters if(!CExpertSignal::ValidationSettings()) return(false); //--- initial data checks // Set input shapes const long _in_shape[] = {1, 6}; const long _out_shape[] = {1, 1}; if(!OnnxSetInputShape(m_handles[m_model_type], ONNX_DEFAULT, _in_shape)) { Print("OnnxSetInputShape error ", GetLastError()); return(false); } // Set output shapes if(!OnnxSetOutputShape(m_handles[m_model_type], 0, _out_shape)) { Print("OnnxSetOutputShape error ", GetLastError()); return(false); } //--- ok return(true); }

Testing was done across the different ‘model types’, where this parameter is an acronym for the three different assets that we are testing while running all three signal patterns, at a go. So, when this integer value is assigned 0 it implied we were testing USD JPY, when it was 1 we were testing XAU USD, and when it was 2 we were testing SPX 500. Our testing aimed at examining if the performance of the signal patterns 5, 6, and 9 could be turned around. Usually, this is done more directly by testing one pattern at a time, but in this case we are unifying all three patterns around the three different tested assets. The use of different testing assets, each geared towards particular market types, constitutes our testing universe.

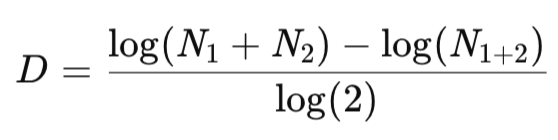

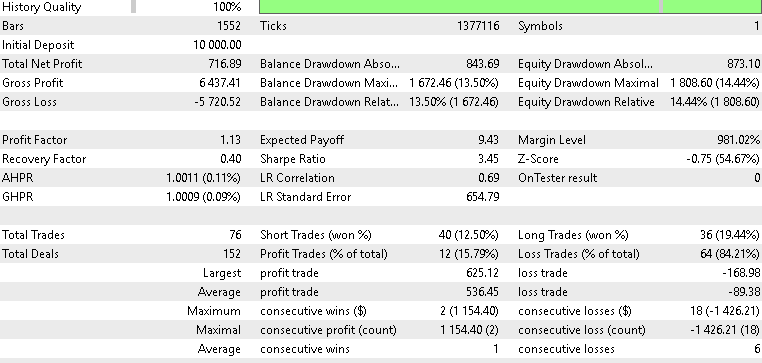

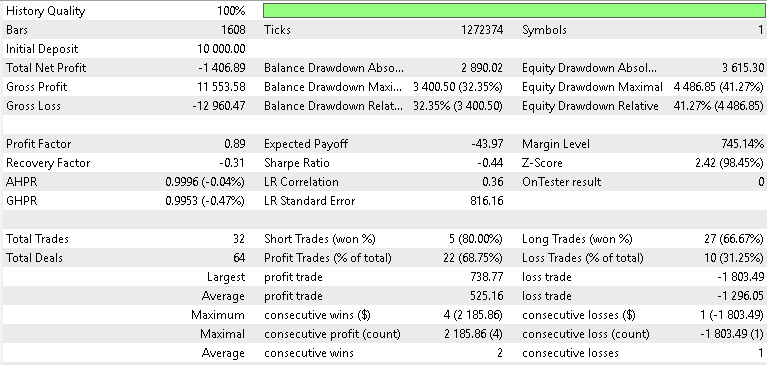

We trained/ optimized from similar test windows that we used in the last article of July 2023 to July 2024. The criteria we tuned were the open and close thresholds for the custom signal, entry price pips which set the distance of our limit orders, and signal pattern thresholds to be accumulated for each pattern should it be present as it is checked on each new bar. The forward walk results were as follows:

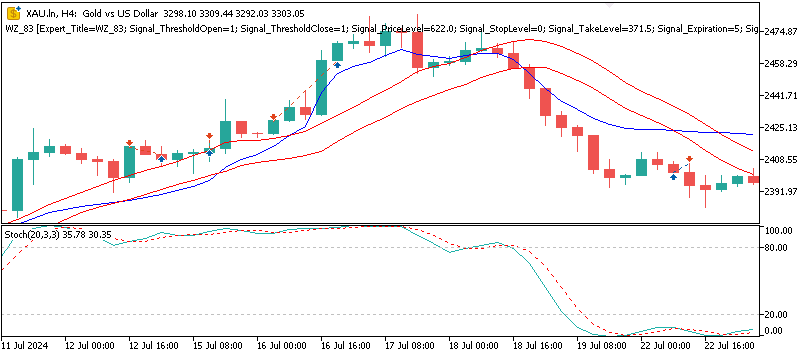

For XAU USD

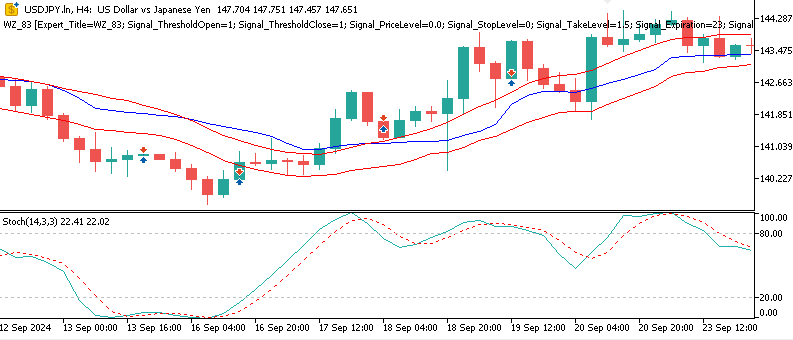

For USD JPY

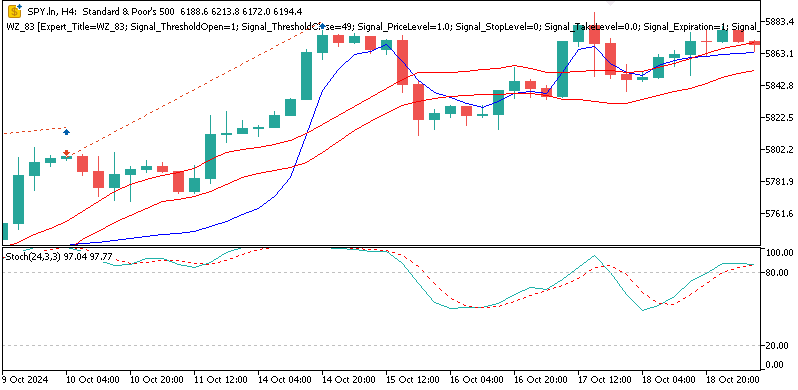

For SPX 500

Our forward test results were mixed but illuminating nonetheless. When testing with Gold, our beta-VAE model posted some profitability of a mild 2.1 percent return over the year, on the 4-hour time frame. We do not get to put apart the latent layer variables and pinpoint which ones are specializing on what signal patterns, however we could surmise that pattern-5’s flat-cross embeddings were able to spot volatility driven reversals in the midst of Gold’s spikes. We also tested with the asset SPX 500, and the return for the year, on the forward walk, was negative 0.8 percent. Similarly, USD JPY on its testing did not do any better, in fact faring worst among the three by posting a -1.4 percent return. On the whole, therefore, only XAU was able to make it past breakeven which means this testing’s performance mostly echoed what we had in the last article, part-84, since the VAE has only given us a modest lift when testing with XAU USD.

Conclusion

To sum up, bringing together the beta-VAE inference model with the indicator pairing of the Stochastic-Oscillator and the Fractal Adaptive Moving Average pairing does provide disentangled hidden features that, to a degree, have shown some applicability. Our ONNX to MQL5 ‘pipeline’ has indicated some gains from the last article, notably with XAU USD; however, it has also emphasized some limits. Forward testing on USD JPY and SPX 500 was lackluster to mediocre at best. This therefore calls for careful feature-engineering, testing that is regime-aware, as well as conservative deployment. All results presented here, as always, are experimental and do require independent testing and diligence before further consideration.

| name | description |

|---|---|

| WZ-84.mq5 | Wizard Assembled Expert Advisor whose header lists name and location of referenced files |

| SignalWZ-84.mqh | Custom Signal Class file |

| 84-XAU.onnx | Gold trained ONNX Model |

| 84-USDJPY.onnx | Dollar-Yen trained ONNX model |

| 84-SPY.onnx | SPX 500 trained model |

Warning: All rights to these materials are reserved by MetaQuotes Ltd. Copying or reprinting of these materials in whole or in part is prohibited.

This article was written by a user of the site and reflects their personal views. MetaQuotes Ltd is not responsible for the accuracy of the information presented, nor for any consequences resulting from the use of the solutions, strategies or recommendations described.

Royal Flush Optimization (RFO)

Royal Flush Optimization (RFO)

Price Action Analysis Toolkit Development (Part 46): Designing an Interactive Fibonacci Retracement EA with Smart Visualization in MQL5

Price Action Analysis Toolkit Development (Part 46): Designing an Interactive Fibonacci Retracement EA with Smart Visualization in MQL5

The MQL5 Standard Library Explorer (Part 2): Connecting Library Components

The MQL5 Standard Library Explorer (Part 2): Connecting Library Components

Introduction to MQL5 (Part 24): Building an EA that Trades with Chart Objects

Introduction to MQL5 (Part 24): Building an EA that Trades with Chart Objects

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use