Statistical Arbitrage Through Cointegrated Stocks (Part 6): Scoring System

Introduction

We have reached our first milestone for a fully automated statistical arbitrage pipeline through cointegrated stocks. We’ve developed Python classes for the cointegration tests, we’ve set up and evolved an initial database, and we have an Expert Advisor ready to be put to work to test strategies. With some glue code, the model that informs the strategy parameters to the EA can even be updated in real-time by sourcing data from the database. It was a long journey towards the implementation of our statistical arbitrage framework for the average retail trader. We have even defined a step-by-step process for screening our stocks from the whole universe of Nasdaq-listed companies down to a dozen of semiconductor-related securities. However, we lack a scoring system.

With the screening workflow in mind, we are now ready to define a scoring system and backtest it. The previous article was left with an outline of the possible criteria for it.

- Strength of Cointegration

- Number of Cointegrating Vectors (Rank)

- Stability of portfolio weights

- Reasonable spreads

- Time to reversion

- Liquidity

- Transaction costs

Besides these criteria, we may add two other not mentioned in that outline:

- Timeframe (Data frequency)

- Lookback window

The question is: how to find the values and choose the weight of each criterion? It seems clear that we will end with some kind of 'weighted points attribution' to each criterion, but how to weigh them? How to choose which of them will have more relevance than the other, if any? How to establish a hierarchy of these criteria? Which comes first, and which goes to the end of the ranking process? By having a clear definition for how to weigh these criteria, we fill the gap between a theoretical description of a model and a testable, practical, and potentially usable trading system.

We are proposing a scoring system with two main criteria types: eliminatory, and classificatory ones.

Eliminatory criteria are those that disqualify a basket. It doesn’t matter how well the basket scores on other factors; if it doesn’t achieve a chosen threshold in these criteria, the basket should be sent to the end of the line. These criteria are deal-breakers.

Classificatory criteria, on the other hand, compose the ranking system properly.

Besides these two main criteria, eliminatory and classificatory, we have two criteria that can be eliminatory or classificatory, depending on our trading goals. They are strategic criteria.

Scoring system

Eliminatory criteria

By having eliminatory criteria, we are ensuring that we’ll be only evaluating baskets that are actually tradable. Even a perfect basket, from a statistical perspective, is worthless if it can be traded efficiently. We should consider applying a high negative weight to them.

But why not exclude them in the screening filter we saw in the previous article? Because the values that inform these criteria are not written in stone. They can, and probably will, change over time. That’s why we have an initial screening filter. It is when we select those securities that fits in our broad strategy as a whole (markets, sector, industries, etc.). Then we have a second stage where we pass those securities through our scoring filter. While the screening step will select among thousands of potential candidates, the scoring step will define which is better among a relatively small number of candidates. By definition, the scoring must tell us what our ideal pair or basket to be traded right now is.

Liquidity- Liquidity is an indispensable criterion because spreads involving illiquid stocks may be costly to trade. We need reasonable spreads, and not only for stat arb. The traded volume in a given period is the most obvious indicator of the liquidity of a security. The greater the volume, the greater the liquidity, with a direct relationship with the spreads.

From the Metatrader 5 documentation, we learn that trading volumes mean different things for decentralized markets, like Forex, and centralized ones, like stocks:

“For the Forex market, 'volume' means the number of ticks (price changes) that appeared in the time interval. For stock securities, volume means the volume of executed trades (in contracts or money terms).”

Traded volume and related spreads are not the only factors we should take into account when assessing the liquidity of a security. The depth-of-market must be taken into account too if we were trading exceptionally high volumes, which is not our case here. So we will not deal with the DOM for our retail traders’ stat arb framework.

Transaction costs - There are at least three factors of cost that may impact the overall transaction costs, depending on the Exchange, the broker, and the assets included in our basket:

- commissions and/or fees

- the spread

- and the expected slippage.

The spread for liquid Nasdaq stocks like Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), and Nvidia (NVDA) is usually just $0.01 per share at the time of writing, but it can be wider for less liquid ones. In this scoring system, we can assume this value for the most liquid, increasing to the maximum spread of $0.05 for the less liquid ones.

If I’m not wrong, in the majority of the brokers specifying the maximum allowed slippage (the deviation from the last quoted price) is a feature only available for professional accounts, so it is out of the scope of our stat arb framework aimed at the retail (non-professional) trader. Because of this limitation, we must include in our backtests some expected slippage. We can assume 0.05% of trade value per order.

Finally, in regards to commissions and/or fees, let’s consider that, although many brokers offer commission-free trades, regulatory and Exchange fees can still apply. In our backtests, we can use an estimation of $0.005 per share.

To keep it simple in our backtests, we can approximate the total round-trip cost (buy + sell) as 0.1% of the traded value. This simplification should capture spreads, eventual slippage, and commissions/fees altogether. But let’s make it clear that these are approximations based on my own experience, and your mileage may vary broadly away from these numbers. So, as always, you should be doing your due diligence when it comes to this topic.

Classificatory criteria

Classificatory criteria are those that will properly rank our basket candidates.

Strength of Cointegration - We may use the Johansen statistics (trace and maximum eigenvalue) to gauge how strongly the series are cointegrated. Stronger test statistics indicate a more reliable long-run relationship.

Number of Cointegrating Vectors (Rank) - By considering the number of cointegrating vectors, we may assess the desired complexity of the system we are building.

- Rank = 1 indicates a single stable spread. Easier to monitor.

- Rank > 1 indicates multiple possible spreads. More flexible, but also more complex.

Stability of portfolio weights - We may avoid highly varying hedge ratios across different sample windows. It can indicate fragile relationships.

Time to reversion - We may calculate the half-life of mean reversion to assess how quickly the spread reverts to equilibrium.

Strategic criteria

Data frequency (timeframe) and lookback period are more of strategic choices than a quantitative criterion for scoring. It’s less about one being "better" than the other, and more about alignment with our trading strategy. A long-horizon strategy might use daily data, while a strategy for shorter opportunities would use intraday data. So, we don't necessarily "weight" this criterion in the same way as the others. Instead, we’ll use it as a pre-selection filter. We’ll first decide whether our strategy is a long-term one or a short-term one and then screen for baskets using the appropriate data frequency. Data frequency can affect signal timeliness, noise, and transaction costs, so it’s a foundational decision that influences how we would score the other criteria.

Data Frequency (daily, intraday) - Daily data is common for long-horizon strategies, while intraday data can capture shorter-lived opportunities. Higher frequency improves signal timeliness but increases noise and transaction costs.

Lookback Window for stability - The choice of historical window length for correlation and cointegration tests is critical. Short windows adapt quickly to changing market conditions but may capture transient, unstable relationships. Long windows provide more stable estimates but may become outdated if the economic regime changes.

A practical approach is to test multiple window lengths (e.g., 60, 120, 250 trading days) and evaluate how stable the cointegration results remain across them.

We can also use rolling windows to constantly update hedge ratios and test whether the relationship holds out of sample.

Do not confuse this strategic choice of the lookback period with the evaluation of the stability of the lookback windows above. Here we will NOT be evaluating the stability across different lookback windows; instead, we’ll be choosing what lookback to use as a basis for our mean, std dev, and the frequency of parameters updates by the EA. In particular, note that there is no intrinsic tie between the trading timeframe and the lookback period. It is perfectly acceptable, from a trading perspective, that we trade in a daily timeframe and use intraday lookback periods. In fact, in this combination lies some unexpected opportunities, as we’ll see soon.

Establish a scoring workflow

Liquidity

With these criteria in place, we are ready to score our screened baskets. We can start by eliminating those stocks that do not fit our strategy as a whole, which are those with low liquidity. It is an elimination criterion. But, unless we are able to say upfront that we will not include stocks that trade less than X volume/contracts in a given period, liquidity is a relative measure. We need a reference for high/middle/low liquidity; we need to define a threshold for what is acceptable and what is not for a given period.

Liquidity, and by consequence, reasonable spreads, should not be an issue in the specific case of the example we’ve been using here from the start of the series, that is, Nasdaq stocks. They tend to be stocks with relatively high liquidity. However, even among these relatively high liquidity stocks, some of them are more liquid than others. Besides that, we must take into account that at some point we may be screening/scoring non-Nasdaq stocks, or even dealing specifically with small-caps, for any reason. Then, liquidity will certainly be a factor to consider.

Let’s continue with our already filtered stocks from the semiconductor industry. At the time of writing, they amount to sixty-three symbols stored in our database. (If you are not following this series, please take a look at at least the previous article to get the context on how we arrived here after screening.)

![]()

Fig. 1 - Screenshot showing the database interface in the Metaeditor with the market_data table symbol count

As said, all of the Nasdaq stocks are expected to be relatively high liquidity securities. That is the main reason we choose them when developing the features of our statistical arbitrage framework for the average retail trader. But we want to know which ones from the semiconductor subset are the most traded, and also which are the least traded ones.

![]()

Fig. 2 - Screenshot showing the database interface in the Metaeditor with the most liquid semiconductor stock

No surprises here. As expected, Nvidia is the most traded, the most liquid stock in the semiconductor industry, and one of the most traded stocks in the whole world at the time of writing. But this information is of little value. We need an average of each symbol, so we can evaluate them relative to each other.

![]()

Fig. 3 - Screenshot showing the database interface in the Metaeditor with the average traded volume for semiconductor stocks

Remember that for the Forex market, you would be using tick volume here, instead of real volume.

Now we have something useful. If you are not familiar with SQL, maybe you want to take note of this simple query, because you will need it in small variations many times ahead.

SELECT

s.symbol_id,

s.ticker, -- symbol name

ROUND(AVG(md.real_volume)) AS avg_real_volume_int

FROM market_data AS md

JOIN symbol AS s

ON md.symbol_id = s.symbol_id

GROUP BY s.symbol_id, s.ticker

ORDER BY avg_real_volume_int DESC; The ROUND and AVG are two built-in SQLite functions. As you can see by their names, we are using AVG to calculate the average real volume. It is returned as a floating-point value. The ROUND function rounds the result to the nearest integer.

The JOIN clause is used to link each market‑data row to its symbol metadata, so we can have the symbol name from the symbol ID. Finally, we use the GROUP BY to make the result show only one row per symbol.

The cointegration strength

Now that we have our stock symbols from the semiconductor industry ranked by liquidity, it is time to check their cointegration strength. As we did with previous tests (correlation, cointegration, and stationarity), the results of this cointegration strength ranking will also be stored in a separate table for further reuse and comparison. Remember that we are storing every data that can or may be useful in the future when we implement machine learning.

The new coint_rank table has this form.

Fig. 4 - Screenshot showing the coint_rank table fields and datatypes

The table definition is very similar to what we have been doing until here. We keep using the test timestamp as the primary key, since timestamps are a kind of natural key in our domain. Keep using STRICT SQLite tables to avoid surprises with wrong data types, and we maintain the usual checks in the TEXT fields when the allowed inputs are known beforehand, like the cointegration method and the timeframes. The definition below has comments to ease our understanding.

-- Cointegration ranking results (STRICT mode with lookback and timestamp uniqueness) CREATE TABLE coint_rank ( tstamp INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unix timestamp (UTC seconds since epoch) timeframe TEXT CHECK ( timeframe IN ( 'M1','M2','M3','M4','M5','M6','M10','M12','M15','M20','M30', 'H1','H2','H3','H4','H6','H8','H12','D1','W1','MN1' ) ) NOT NULL, lookback INTEGER NOT NULL, -- Lookback period (calendar days) assets TEXT NOT NULL, -- e.g., 'AAPL, MSFT' or 'AAPL, MSFT, GOOG' method TEXT CHECK ( method IN ('Engle-Granger', 'Johansen') ) NOT NULL, strength_stat REAL, -- Engle-Granger: ADF statistic; Johansen: trace statistic p_value REAL, -- Only for Engle-Granger eigen_strength REAL, -- Johansen eigenvalue indicator rank_score REAL, -- Combined ranking score -- Allow multiple test runs for the same combo but unique by timestamp CONSTRAINT coint_rank_unique_combo UNIQUE (timeframe, lookback, assets, tstamp) ) STRICT; CREATE INDEX idx_coint_rank_timeframe_lookback ON coint_rank (timeframe, lookback);

We are using a UNIQUE constraint for the combo tstamp/timeframe/lookback/assets, so we know that for each of these pairs, we will have only one cointegration rank evaluation at each timestamp. Note that although tstamp is already unique by definition, since it is the table's primary key, if we leave it out of the UNIQUE combo, we would not be able to insert more than one run for each timeframe-lookback-assets combination. It would violate the UNIQUE constraint. By including the timestamp in the combo, we can store the same combination with different timestamps to check the stability of the cointegration over time. Later we can filter or aggregate the results by date. This will be useful for our backtesting logs, since each run is self-contained, timestamped, and traceable. Finally, since we’ll mostly query by timeframe and lookback, we’ve created an index for these two columns to speed up things.

Strength stat for the Engle-Granger test

We already talked a lot about how the Engle-Granger and the Johansen cointegration tests work in previous installments of this series, so we’ll save your time by not repeating this information here. Let’s just remember that they measure how tightly a pair or group of stocks move together in the long run. That is, they measure how strongly the price relationship between those assets holds over time. The strength_stat field stores the numerical result of the cointegration test, both for the Engle-Granger and the Johansen.

For the Engle-Granger test, this field stores the ADF (Augmented Dickey-Fuller) statistic applied to the spread between the two assets. Again, we already presented the ADF stationarity test specifics and interpretation in previous articles of this series and we’ll not repeat ourselves here. Enough to remember that it checks if the spread between the two assets fluctuates around a mean instead of drifting away. That is, it checks if the spread is stationary. So, for the Engle-Granger cointegration test, this field is telling us “how much” the spread is stationary.

If you are following our reasoning from the previous parts, by now it should be clear that the smaller the ADF statistic is, the stronger the cointegration; a “more negative” strength_stat field for the Engle-Granger test means the spread is “more” stable.

Strength stat for the Johansen test

When testing not a pair of assets, but a basket of three or more assets, the Johansen cointegration test is the tool we’ve been using to build our weighted portfolios, that is, linear combinations that remain stable over time. We already described this test and how to interpret its results in previous articles. Again, we’ll save your time by inviting you to check those articles. For this test, the strength_stat field in our database stores the “trace statistic”. The higher the trace statistic, the stronger the evidence that some combination of these assets forms a stable long-run equilibrium. The larger the strength_stat, the stronger the evidence that this basket moves together in equilibrium.

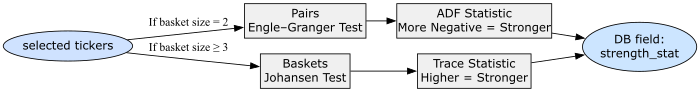

The Python script attached has the following logic for choosing when to use which test and how to obtain their results.

try: if len(basket) == 2: y0, y1 = sub_prices.iloc[:, 0], sub_prices.iloc[:, 1] score, p_value, _ = coint(y0, y1) results.append({ "assets": basket, "method": "Engle-Granger", "strength_stat": float(score), "p_value": float(p_value), "eigen_strength": None }) else: johansen_res = coint_johansen(sub_prices, det_order, k_ar_diff) max_eig = float(max(johansen_res.eig)) results.append({ "assets": basket, "method": "Johansen", "strength_stat": float(max(johansen_res.lr1)), "p_value": None, "eigen_strength": max_eig })

Below, we have a visual representation of the logic.

Fig. 5 - Flow diagram showing how the strength_stat field is filled and its simplified interpretation

Eigen strength

While the Engle-Granger test provides only the ADF that we are storing in the strength_stat field, the Johansen test also has one more measure to help in our scoring: the eigenvalue strength that we keep in the eigen_strength field. For baskets of three or more assets, the Johansen test finds linear combinations (which will be our portfolio weights) of those assets that form stable long-run relationships. Each combination corresponds to a cointegrating vector, and each one has an eigenvalue attached. The eigenvalue measures how “strong” that specific cointegrating relationship is and how tightly the assets move together along that equilibrium direction. A larger eigenvalue means that the assets share a more stable long-term relationship, and also that small deviations from equilibrium tend to correct themselves more quickly.

In our attached script, we take the maximum eigenvalue among all detected vectors:

else: johansen_res = coint_johansen(sub_prices, det_order, k_ar_diff) max_eig = float(max(johansen_res.eig)) results.append({ "assets": basket, "method": "Johansen", "strength_stat": float(max(johansen_res.lr1)), "p_value": None, "eigen_strength": max_eig })

The Johansen trace statistic (strength_stat) tells us how tightly the group moves as one, that is, how stable the relationships are. The maximum eigenvalue (eigen_strength) tells us how stable the most stable relationship is among them. Thus, a high eigen_strength tells us that the group moves in a very tight formation, while a low eigen_strength tells us that they drift apart more easily, even if cointegrated.

Rank score

The field rank_score is the final summary metric that our scoring script produces, the one that decides which baskets look strongest and deserve trading attention. After we run the cointegration tests, we need a single comparable number for all results, whether they come from Engle-Granger pairs or Johansen baskets. This single number is the rank_score. We can think of the rank_score as a normalized cointegration strength index that allows us to sort and rank all our candidate relationships from strongest to weakest.

You will find it in this piece of our attached scoring script:

df = pd.DataFrame(results) df["rank_score"] = df.apply(lambda row: -row["p_value"] if row["method"] == "Engle-Granger" else row["eigen_strength"], axis=1) df = df.sort_values("rank_score", ascending=False).reset_index(drop=True)

For the Engle–Granger (Pairs), the test gives a p-value. Smaller p-values mean stronger evidence of cointegration. To make stronger pairs sort higher in the final ranking, we negate the p-value:

rank_score=−p_value

So a p-value of 0.01 becomes -0.01, which sorts above a weaker one like -0.20. The lower the p-value, the higher (less negative) the rank_score, so the pair is ranked as more cointegrated.

For Johansen (Baskets), the test doesn’t produce a single p-value, but several eigenvalues. Our script takes the largest eigenvalue, stored in eigen_strength, and uses it directly as the rank_score.

rank_score=eigen_strength

A higher eigenvalue means a higher rank_score, a stronger basket.

For simplicity and the ease of analysis, the rank_score puts all pairs and baskets on the same page. It doesn’t care which test they came from, only how strong the relationship is. We can use SQL to filter the results as we please (after all, that is the main reason why we are using a database, isn't it?). When we sort by rank_score (descending), we get the most stable and statistically significant price relationships at the top of our list.

![]()

Fig. 6 - Screenshot of the database interface in the Metaeditor showing the coint_rank table with assets from the semiconductor industry

Here, we selected the ten most liquid assets shown in Figure 3 above and ran the attached cointegration ranking script for all combinations of two, three, and four symbols, all of them for the H4 timeframe. This timeframe is part of our strategic criteria. Figure 6 above shows the first run we did for the 60-day lookback period. The Metaeditor highlight in blue shows the level at which the ranking transitions from Johansen to Engle-Granger values. The result set is full, no filters applied yet.

You will note that there are 375 results for this single run (this table was empty before the run). This is the number of possible combinations (not permutations) for 10 symbols, grouped by 2, 3, or 4. Keep in mind this number when doing your own tests, because you need to take into account the “combinatorial explosion” you may have to deal with. That is the reason why, besides being our “strategic criteria” for demonstration purposes, I’ve chosen a single timeframe to test here. Also, this is the reason why I limited the number of symbols per basket to four. Later, we’ll need to test for several lookback periods, since without the comparison between several lookback periods, this ranking is of little help, or at least, very fragile. If we include more symbols and timeframes, we start requiring a lot more resources, both in computational power, time, and data. Keep this in mind and adapt the numbers to fit your resources to your objectives, instead of the other way around.

Here we have the top of the same table.

![]()

Fig. 7 - Screenshot of the database interface in the Metaeditor showing the top of the coint_rank table

Note that the top of the table is dominated by Johansen results. This is expected, since it tends to find stronger relationships than Engle-Granger. But also take into account that we have a tiny sample here, with only one timeframe (H4) and one lookback period (60 days).

However, even with this limited sample, some patterns start to emerge, like the one highlighted with three lines in Figure 7. We have six symbols involved in three baskets of four symbols, but changing one of them has little effect on the result. This may suggest that the other three symbols, those that do not change in the basket (NVDA, MU, and ASX), are the “real source” of the cointegration. Then we find this trio composing their own basket five lines below, so they have a weaker cointegration than when the others were present in the basket. Why? It was not expected that they would be the solid base of the cointegration? Well, I don’t know the answer yet. But I’m sure that as we evolve, analysing these ten symbols, we will find many patterns like these, along with others even more “unexpected”. And many of them will be tradeable patterns that we would not be able to find if not with the help of data analysis. That is the beauty of statistical arbitrage and, in this matter, the beauty of data-driven trading in general.

We will have plenty of time to look for these patterns in our data, both manually and by visualizing plotted results. For now, let’s concentrate on our initial goal of automating this workflow to feed the strategy table we’ve created to be the “single source of truth” for our Expert Advisor.

Once our coint_rank table is filled with data from the ten most liquid symbols, for the H4 timeframe, and the lookback periods from one to six months, we will have the most cointegrated basket at the top of the results when sorting by descending rank_score.

Remember that our initial trade hypothesis is looking for stocks cointegrated with NVDA. So, let’s check it.

Fig. 8 - Screenshot of the database interface in the Metaeditor showing the coint_rank table

Here we are using the LIKE operator from SQLite to filter only the baskets and pairs that include NVDA in any position.

“The LIKE operator does a pattern matching comparison. The operand to the right of the LIKE operator contains the pattern, and the left-hand operand contains the string to match against the pattern. A percent symbol ("%") in the LIKE pattern matches any sequence of zero or more characters in the string.” (You can find more in the SQLite docs.)

If we want to trade pairs, not baskets, we filter by the cointegration test method, asking only for the Engle-Granger method. (We could have filtered the above query as well, asking only for the Johansen test, but it was not necessary because, as said, Johansen results afloat above Engle-Granger results).

Fig. 9 - Screenshot of the database interface in the Metaeditor showing the coint_rank table filtered for the Engle-Granger test

We can see that we have at least one strong candidate for a basket on the 60-day lookback, and two good candidates for pairs trading, being one for the 180-day lookback and the other for the 60-day lookback. Let’s stick with the basket, since this is what we have been doing, and let the pairs for your experiments (in the first article of this series, you will find a pairs-trading EA to test them at will).

To backtest the stronger basket, we need the portfolio weights. We will use the script we presented in the previous article, coint_johansen_to_db.py, to obtain the portfolio weights and, at the same time store the test results in the coint_johansen_test for future analysis.

if __name__ == '__main__': analyzer = SymbolJohansenMulti() # Our best-ranked NVDA cointegrated basket analyzer.run_johansen_analysis( asset_tickers=['NVDA', 'INTC', 'AVGO', 'ASX'], timeframe='H4', lookback=60 )

If everything goes well, you should have an output like this in your terminal.

PS C:\...\StatArb\coint> python .\py\screening\coint_johansen_to_db.py

Successfully connected to the SQLite database.

Fetching data for symbol: NVDA...

Fetching data for symbol: INTC...

Fetching data for symbol: AVGO...

Fetching data for symbol: ASX...

Johansen test results for 4 assets:

Cointegrating rank: 1

Trace Statistics: [56.636209656616835, 14.38576476690755, 5.106951610164332, 1.355015009275225]

Max-Eigenvalue Statistics: [42.250444889709286, 9.278813156743219, 3.7519366008891066, 1.355015009275225]

Cointegrating Vectors: [1.0, -1.9598590335874817, -0.36649674991957104, 21.608207065113874]

Successfully stored Johansen test results for 4 assets with test_id: 21.

Database connection closed.

Analysis complete.

The last step is to insert these values in our ‘strategy’ table to be read by our Expert Advisor and backtest it.

The backtest

While the Metatrader 5 integrated SQLite database is fully available when trading, we cannot read SQLite databases from the Strategy Tester. I suppose the reason is that Strategy Tester uses a separate agent folder (implying sandboxing). During testing, all file operations are performed in the local testing agent folder, not in the regular terminal MQL5\Files. We could export the ‘strategy’ table to a CSV file and read it at the start of the backtest in the EA OnInit() event handler. This would allow us to read the ‘strategy’ table, but we still would not be able to update the model in real-time while backtesting, which is the main goal of having the database as the model data source. But, no panic! We can verify how the real-time model updates are behaving in a demo account. For now, let’s just hardcode the model parameters in the EA and backtest each strategy separately.

Since we are using MQL5 Algo Forge, the new Git backed MQL5 Storage, we can easily see the changes we made in our EA to include these parameters.

// Input parameters input int InpUpdateFreq = 1; // Update frequency in minutes -input string InpDbFilename = "StatArb\\statarb-0.3.db"; // SQLite database filename -input string InpStrategyName = "CointNasdaq"; // Strategy name +input string InpDbFilename = "StatArb\\statarb-0.4.db"; // SQLite database filename +input string InpStrategyName = "CointNasdaq_H4_60"; // Strategy name input double InpEntryThreshold = 2.0; // Entry threshold (std dev) input double InpExitThreshold = 0.3; // Exit threshold (std dev) input double InpLotSize = 10.0; // Lot size per leg @@ -53,18 +53,40 @@ int OnInit() // Set a timer for spread, mean, stdev calculations // and strategy parameters update (check DB) EventSetTimer(InpUpdateFreq * 60); // min one minute -// Load strategy parameters from database - if(!LoadStrategyFromDB(InpDbFilename, - InpStrategyName, - symbols, - weights, - timeframe, - lookback_period)) +// check if we are backtesting + if(MQLInfoInteger(MQL_TESTER)) { - // Handle error - maybe use default values - printf("Error at " + __FUNCTION__ + " %s ", - getUninitReasonText(GetLastError())); - return INIT_FAILED; + Print("Running on tester"); + ArrayResize(symbols, 4); + ArrayResize(weights, 4); + //{"NVDA", "INTC", "AVGO", "ASX"}; + symbols[0] = "NVDA"; + symbols[1] = "INTC"; + symbols[2] = "AVGO"; + symbols[3] = "ASX"; + // {1.0, -1.9598590335874817, -0.36649674991957104, 21.608207065113874}; + weights[0] = 1.0; + weights[1] = -1.9598590335874817; + weights[2] = -0.36649674991957104; + weights[3] = 21.608207065113874; + timeframe = PERIOD_H4; + lookback_period = 60; + } + else + { + // Load strategy parameters from database + if(!LoadStrategyFromDB(InpDbFilename, + InpStrategyName, + symbols, + weights, + timeframe, + lookback_period))

You can see that we updated our database filename to reflect the schema changes (we added the coint_rank table), and the strategy name to indicate the cointegration test that generated its parameters, making it more specific.

We also added a check to know if we are running in the Strategy Tester environment, that is, if we are running a backtest. If this is the case, we will not source the parameters from the database. Instead, we will use the hardcoded strategy parameters.

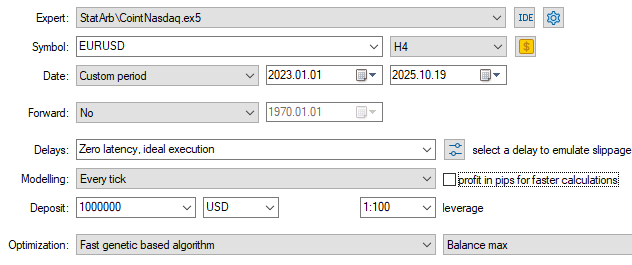

These are the backtest settings and the inputs used in it. You will find both the backtest configuration settings (.ini) and the backtest input (.set) files attached at the bottom of this article.

Fig. 10 - Screenshot showing the backtest settings

Note that we ran the backtest over a period of two and a half years, since the beginning of 2023, despite the fact that our strategy has a lookback period of 60 days. Also, we left the ‘Delays’ field set for ideal execution (zero latency), even knowing that it may be a critical factor for statistical arbitrage strategies.

Both choices are related to the fact that the main goal of this first backtest is to evaluate the strategy’s long-term stability, not its potential profitability yet. So, why not set the cointegration test lookback period to two years and a half in the first place? Because we are scoring for the most cointegrated now, at the moment, we are considering the trade. Long-term stability is one more factor to take into account in our scoring system, but when ranking the baskets, we are interested in the most cointegrated ones today.

When it comes to zero latency, it should not make any difference here. Remember when we chose to trade in higher timeframes to avoid the unfair competition with the statistical arbitrage big players? There we were trading in the one-minute timeframe. Now we are on the H4 timeframe, in a more relaxed swing trading environment .

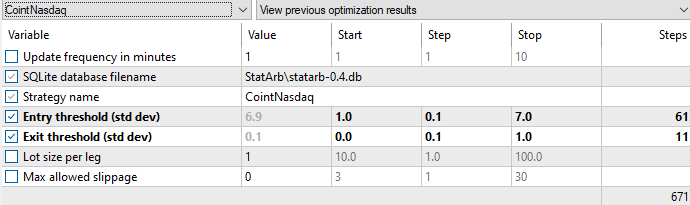

Fig. 11 - Screenshot showing the backtest inputs

Figure 11 shows that we did some optimizations to choose the best entry and exit threshold, both of them calculated as standard deviations from the mean. The 6.9 and 0.1, respectively, were the values used in the backtest.

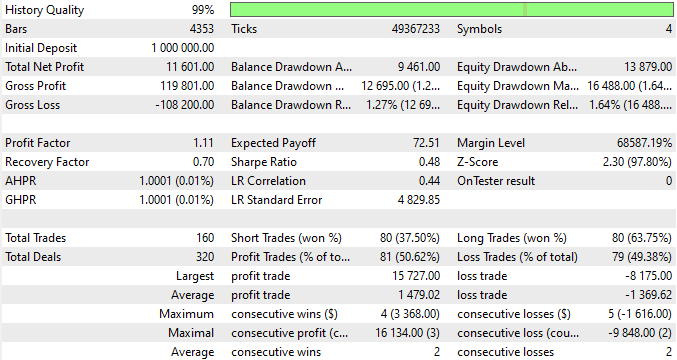

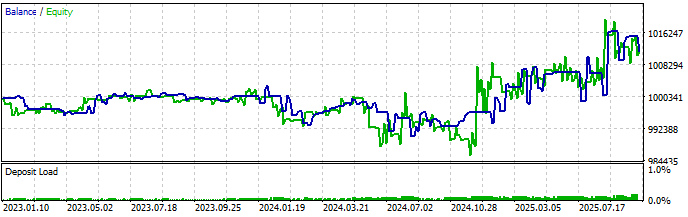

These are the backtest results.

Fig.12 - Backtest report showing the resulting stats

The EA opened 160 trades, averaging 4.7/month in 34 months. Let’s say one trade per week on average, which should be a good holding time for a swing trade. Also, the average profit trade (1,479.02) is higher than the average loss trade (-1,369.62), with minimal balance drawdown (1.27%). Although the profitability was not the backtest's main goal, taking the whole picture, it sounds promising.

Fig. 13 - Backtest showing the equity/balance graph

The balance/equity graph is a bit better than what I was expecting, because it became profitable around November 24, and our cointegration test lookback period was very short (60 days).

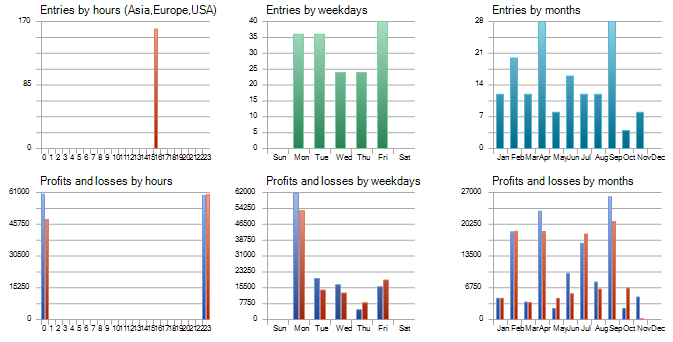

Fig.14 Backtest report showing trading entry days and times

“Sifting through Straus’s data, Laufer discovered certain recurring trading sequences based on the day of the week. Monday’s price action often followed Friday’s, for example, while Tuesday saw reversions to earlier trends. Laufer also uncovered how the previous day’s trading often can predict the next day’s activity, something he termed the twenty-four-hour effect. The Medallion model began to buy late in the day on a Friday if a clear up-trend existed, for instance, and then sell early Monday, taking advantage of what they called the weekend effect.” (from Gregory Zuckerman’s book, The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simmons launched the quant revolution, New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin, 2019)

Did you note the pattern in the entry by hours above? All the 160 trades were opened at the same hour, 16:30 PM to be exact.

I’m assuming we are talking UTC time in the Strategy Tester.

“During testing, the local time TimeLocal() is always equal to the server time TimeTradeServer(). In turn, the server time is always equal to the time corresponding to the GMT time - TimeGMT(). This way, all of these functions display the same time during testing.” (The Fundamentals of Testing in Metatrader 5)

To be honest, I think that it is pretty weird that all trades have the same opening time. It can be true, as it can be due to some EA’s unexpected behavior. Anyway, this is the closing time of the London Stock Exchange, and patterns like these are what we can expect to find when analysing data for statistical arbitrage, as the quote above illustrates.

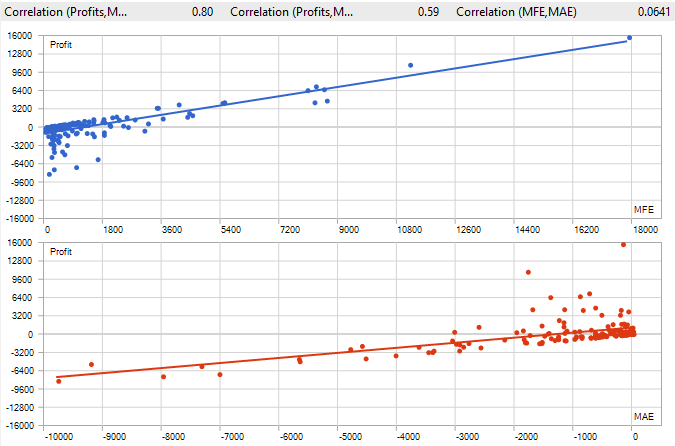

Fig. 15 - Backtest report showing MFE and MAE

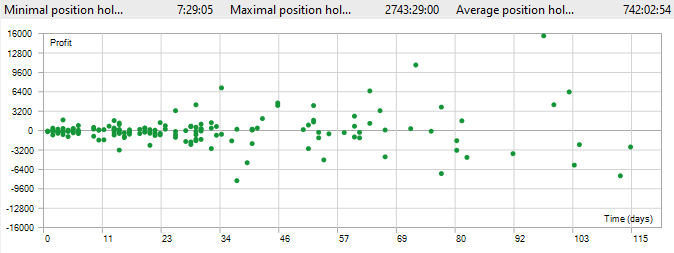

Both the MFE and the MAE suggest that, for this system, we should consider adding a threshold for close positions by hold time, which is corroborated by the maximum and average position holding times below. For more information about MFE and MAE, you may check this great article about the mathematics in trading.

Fig. 16 - Backtest report showing the position holding times

It seems like we had at least one position that remained open for about 15 weeks! And even the average position holding time of about a month seems to be a bit high for this kind of strategy.

But we will look at these issues ahead. By now, it’s enough to understand the principles behind the scoring system and adapt it to your style and trading objectives. As John Von Neumann once said, “truth is… much too complicated to allow for anything but approximations.”

Happy trading!

Conclusion

In this article we propose a scoring system for statistical arbitrage through cointegrated stocks. It starts with the strategic criteria like the timeframe and the lookback window for cointegration tests, then eliminatory criteria like liquidity and transaction costs are applied to discard securities that aren't worth the trading costs, or that are not tradeable at all.

Finally, the ranking score is properly built based on the strength of cointegration, the number of cointegration vectors, the stability of portfolio weights, and time to mean-reversion. We presented a sample implementation for the first two classificatory criteria in this article, leaving the portfolio weights stability and the mean-reversion half-time for the next instalment.

We presented and commented on the results of the backtest based on the two classificatory criteria, and we provided the required files for reproduction of the cointegration tests and the backtest itself, so the readers can get started immediately with the proposed statistical arbitrage strategy and this scoring system.

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| backtests\CointNasdaq.EURUSD.H4.20230101_20251019.000.ini | Backtest configuration settings |

| backtests\CointNasdaq.set | Backtest inputs (SET file) |

| Experts\StatArb\CointNasdaq.mq5 | Expert Advisor MQL5 source file |

| Files\StatArb\schema-0.4.sql | Database schema (SQL file) |

| Include\StatArb\CointNasdaq.mqh | Expert Advisor MQH (header) file |

| coint_ranker_auto.py | Python script for ranking cointegration results |

Warning: All rights to these materials are reserved by MetaQuotes Ltd. Copying or reprinting of these materials in whole or in part is prohibited.

This article was written by a user of the site and reflects their personal views. MetaQuotes Ltd is not responsible for the accuracy of the information presented, nor for any consequences resulting from the use of the solutions, strategies or recommendations described.

Price Action Analysis Toolkit Development (Part 47): Tracking Forex Sessions and Breakouts in MetaTrader 5

Price Action Analysis Toolkit Development (Part 47): Tracking Forex Sessions and Breakouts in MetaTrader 5

Introduction to MQL5 (Part 26): Building an EA Using Support and Resistance Zones

Introduction to MQL5 (Part 26): Building an EA Using Support and Resistance Zones

Building a Smart Trade Manager in MQL5: Automate Break-Even, Trailing Stop, and Partial Close

Building a Smart Trade Manager in MQL5: Automate Break-Even, Trailing Stop, and Partial Close

From Novice to Expert: Parameter Control Utility

From Novice to Expert: Parameter Control Utility

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use