Why Stock Traders Should Want The U.S. To Stay Alive In The World Cup

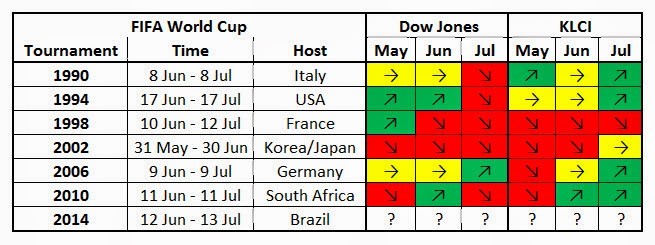

The U.S. Men’s National Team puts its World Cup life on the line against Germany Thursday, with a win or tie assuring the squad advances to the knockout round and a loss putting the American team at the mercy of tiebreakers with Ghana or Portugal. That may not seem to have much to do with stocks, but it turns out a loss in the World Cup has an odd relationship to equity markets.

U.S. forward Clint Dempsey celebrating his goal against Portugal on June 22

According to research from Alex Edmans, an associate professor of finance at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, stock markets of losing countries experience an “abnormal stock return” of negative 38 basis points (0.38%) the day after losses in the World Cup group stage, a figure that rises to negative 49 basis points (0.49%) following losses in the knockout stage, which the U.S. hopes to reach following Thursday’s match with Germany.

The effect is “stronger in small stocks and in more important games,” Edmans and his colleagues found and from here out the games only get more crucial for the Stars and Stripes. Thursday’s showdown comes after a stirring win over Ghana, thanks to a late goal by substitute defenseman John Brooks, and a tie snatched from the jaws of victory against Portugal when superstar Cristiano Ronaldo stole the win from the U.S. with a brilliant last-second assist.

The research by Edmans’ and his colleagues controls for other factors that can impact national markets, in order to achieve a “soccer-related return” that equals the average loss figures above. While most market participants would dismiss such statistics as mere quirks, the World Cup tendencies are just one example of the type of anomalies that make their way into investing legend. Like the others that follow, the likely impact of a Wall Street move based on a World Cup exit falls somewhere in the grey area between gospel and gimmick.

The January Effect

In 1976, researchers Michael Rozeff and William Kinney Jr. found that equally-weighted indices of all stocks on the New York Stock Exchange had abnormally high returns in January as compared to other months, an impressive 3.5% while all other months averaged a measly 0.5%. Some theorize prices tend to swell in January because investors sell in December to lessen tax burdens through capital losses. Others say the trend may result from investors looking to spend cushy year-end bonuses on new investments. If you’re looking for the real January winners though, look to small caps. According to University of Pennsylvania professors Marshall Blume and Robert Stambaugh, small company stocks beat the market in January for 65 out of the 70 years between 1926 and 1995. But get over your New Year’s hangover quickly. Blume and Stambaugh’s colleague Donald Keim found that 50% of those excess returns occur in the first five trading days of the years.

The Weekend Effect

Studies by the Federal Reserve have shown markets see negative returns while investors are away from their desks over the weekend. Similar to the January Effect, the Weekend Effect has the most influence on smaller firms, which usually boast the highest returns among all-sized company stocks. This phenomenon can be explained by the tendency of investors to sell stocks on Friday afternoon to lock in gains or avoid the risk of an adverse development over the weekend. Richard Rogalski, professor at the Tuck School of Business, performed additional research on this effect and discovered weekend returns actually move in the opposite direction during the first month of the year.

The Hemline Index

Vogue may be creating more issues than they think. According to economist George Taylor’s Hemline Index, markets rise and fall with the length of skirts in women’s fashion. The theory is pretty simple — hemlines climb during periods when people feel free and easy about the economy, and descend when things get more uptight. Although this may seem utterly bizarre, there are examples. The micro-miniskirt trend of the 1960s coincided with notable economic expansion, which came to a screeching halt when both maxi skirts and stagflation became household terms in the 1970s. A similar pattern emerged in 1929 when flappers’ daringly short dresses disappeared from the pages of fashion magazines, sending hemlines and the stock market into a downward spiral. Don’t start flipping through the pages of your Macy’s catalog so quickly though, the theory is far from ironclad and is roundly criticized by market-watchers.

The Turn of the Month Effect

Take a pen and mark the turn of the month on your calendars. Studies of the stock market have shown there is a temporary price increase during the last and first three days of each month. In fact, this short four-day period has a higher combined return than all 30 days in a month. It is important to note returns during the second half of a month are negative, meaning that a significant portion of gains must occur during the first two weeks and turn of the month. Researchers have ascribed this strange price pattern to the timing of monthly reinvestments of pension fund distributions in the stock market.

The Holiday Effect

It’s never too early to start a holiday celebration. In studies replicated by many researchers, it has been determined that the Dow Jones industrial average has abnormally positive performance the day before national holidays. The economically and statistically significant trend is pretty shocking. For the 90 years preceding 1987, 51% of capital gains occurred during these few days. For an equal-weighted index of stocks, a mean return of 0.529% on “pre-holidays” is nine times greater than other days.

Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur Effects

University of California, Los Angeles professor Avanidhar Subrahmanyam believes market movements are in sync with the mood swings of Jewish traders, who are in good spirits when celebrating the Jewish New Year and solemn during Yom Kippur, a holiday of repentance. In a 2004 study, Subrahmanyam discovered the S&P 500’s daily return is 22 basis points higher than its 4 basis point average during the Jewish New Year, also known as Rosh Hashanah. Only 10 days later during Yom Kippur, the S&P 500 underperforms by an average of 29 basis points and new years’ cheers subside. In additional research, he did not find any significant patterns during other religious holidays when markets remain open.