As long as the ECB is printing money, no central bank can lift interest rates

European Central Bank President Mario Draghi controls global interest rates, which means the U.S. and the U.K. won’t be raising rates any time soon.

LONDON - Maybe right after Christmas. Perhaps in the spring. Certainly before the summer. In the City, highly paid analysts and economists are still sketching out scenarios for when the Bank of England will hike interest rates for the first time in seven years.

Likewise, on Wall Street an even larger army of Fed watchers is trying to calculate when Janet Yellen will start to tighten policy. It didn’t happen in September, despite widespread expectations that it might. But December is still on the table, and next year looks more likely than not.

While the ECB is still aggressively pumping money into the system, it is impossible for other central banks to tighten.

And yet, in reality, most of them should stop bothering. Why? Because the European Central Bank is now driving this process, and it is likely to keep rates at zero, not just for the euro bloc it manages, but for the world.

The logic is very simple. While the ECB is still aggressively pumping money into the system, it is impossible for other central banks to tighten. Through the currency markets, it would wreak too much havoc on their own economies. And since it looks impossible for rates to rise in Europe any time soon, they are not going to rise anywhere else.

When he is not talking about the European Union, or about climate change, Bank of England Gov. Mark Carney likes to spend his time warning everyone of an imminent rise in interest rates. Carney argued that borrowers should be preparing themselves for a rate rise that was a “possibility,” although he added “not a certainty.”

Back in July, he told a parliamentary committee that “the point at which interest rates rise is getting closer.” He has been wheeling out the same remarks every few weeks for the last couple of years.

And yet, despite that, the day when rates actually do go up never seems to arrive.

It is much the same for the Federal Reserve.

At a meeting of the International Monetary Fund in Lima earlier this month, Fed Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer argued that a rate rise was still a possibility during the remaining months of 2015. New York Fed President William Dudley has made precisely the same point, along with a succession of senior officials. And perhaps it is a possibility, just as a rate rise at the September meeting was, at some point at least, on the cards.

And yet, just like the Bank of the England, the day itself never seems to quite arrive.

So what is holding them back?

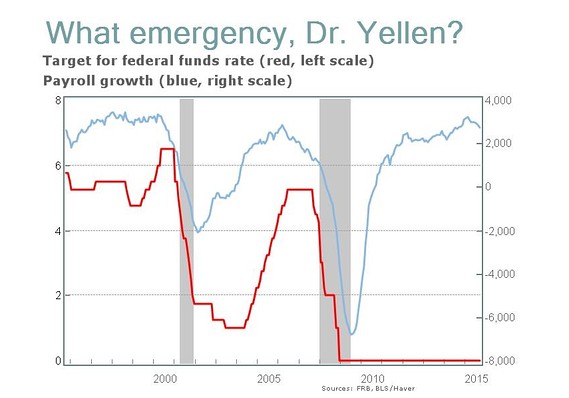

The federal funds target rate has been near zero since 2008, but the economic emergency that inspired such low rates is long since over.

In the U.K., it is very hard to see any credible case for holding rates at a 300-year “emergency” low. In the latest quarter, growth has slowed a little, but at 0.5% over three months it is still respectable by any historic standards for a mature, not-very-exciting economy such as Britain. Employment is at an all-time high, and wages are growing by 3% annually, a more than decent rate.

If that is an emergency, then it is very hard to imagine what normal looks like. Much the same is true of the United States. Growth is decent, and jobs are being created. It is easy enough to understand the case for rates being low. But close to zero? Just like the U.K., it is hard to describe the American economy as facing an emergency.

Here’s the real problem. While the ECB is still aggressively trying to pump up its economy with cheaper money, it is going to be very hard for any other major central bank to raise rates at all.

The ECB launched a massive program of quantitative easing in March. So far it has not had very much impact. The exchange rate has hardly budged, equity prices are actually down a bit on their levels of the spring, and — Spain and Ireland aside — the property market remains subdued.

Despite that, ECB President Mario Draghi looks determined to double down on the policy. At a press conference last week, he said the bank was exploring options for expanding QE. The bet in the markets is now that there will be more action in December, pumping more money into the system. If it doesn’t happen then, it probably will early in 2016.

The ECB does not exist in isolation, however. The eurozone is far too big an economic bloc for that. With a gross domestic product of more than $13 trillion, the eurozone represents 21% of global output. It is a similar amount to the United States, and more than China or Japan.

Can the Fed allow the dollar to soar against the euro? Probably not.

Already, other central banks have responded to the ECB’s moves. The Swiss broke their peg with the euro EURCHF, +0.0275% , and introduced negative rates. The Danes held their peg EURDKK, -0.0027% , but also took rates into negative territory. If they didn’t, the exchange rate for both countries would soar. In the last few days, the Swiss have said they will have to cut rates even more. There is no other option.

Those are fairly minor banks. But big ones are impacted as well.

The U.K. is the most obvious example. Around 16% of the U.K. economy consists of exports to the eurozone. If the exchange rates soars, because the U.K. raises rates while the ECB prints more money, exporters will get hammered. Is the bank seriously meant to allow that happen, especially while there is no threat from inflation — remember prices are falling again in Britain.

The U.S. is not so dependent on exports. But corporate profits are influenced heavily by overseas earnings, and that determines the stock market. Can the Fed allow the dollar to soar against the euro EURUSD, +0.0996% ? Probably not.

In reality, so long as the ECB is aggressively printing money, it will be very hard for any other central bank to raise rates. And the ECB doesn’t look likely to stop soon. The conclusion?

Rates in the U.K. and the U.S., and in other economies as well, are going to remain at zero for a lot longer than most people have yet realized. Officials will warn of rate rises, no doubt. But until the ECB joins in, there is no need to listen to them — it isn’t going to happen.