Financial contagion usually follows a surprise.

Remember the 2008 Wall Street meltdown, for instance, when the US housing market

had had a boom.

Private

financial institutions, in a desire to profit from the bonanza, purchased securities issued by the

mortgage lenders

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac - government-sponsored enterprises.

As a result, investors implicitly assumed that securities issued by the two mortgage lenders were backed by Uncle Sam, explains Deutsche Welle. But at least initially, their assumption was wrong.

Fannie and Freddie's securities were not supported in the same way as US Treasury bills. Thus, when the boom went bust, financial institutions were exposed to more risk than they had anticipated. As the crisis spread through the US and global financial systems, the federal government was ultimately forced to intervene and bail out Fannie and Freddie.

Carmen

Reinhart, an economist who researches financial contagion at Harvard's

Kennedy School of Government, commented that financial organizations had

drastically underestimated the riskiness of these assets, which made

for really fast and furious contagion.

Hardly similar to Greece

Greece has been scraping through a sovereign-debt crisis since 2010, and the private sector has had wide opportunities to reduce its exposure over the past five years.

"The more time you see that a country is being downgraded, that the assessment points to a higher probability of default, you have time to unwind that exposure," Reinhart said, adding that it has been essentially what has happened since 2010. In the meantime, the public sector has widened its role in financial markets since the crisis of 2008, trimming the risk of contagion.

Michael Bordo, an economic

historian at Rutgers University said in an interview with Deutsche Welle

that we are not going to repeat 2008.

"There's been almost an overreaction to 2008 in terms of intervention by central banks and governments and the tightening of the safety net."

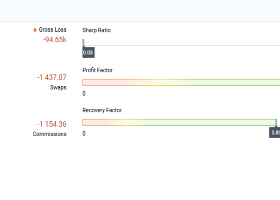

According

to data compiled by Bloomberg, the private sector now holds just 17

percent of Greece's debt. 80 percent belongs to the International

Monetary Fund, the European Central

Bank and the European Union.

Reinhart notes that the distinction between private and public sector

exposure is important.

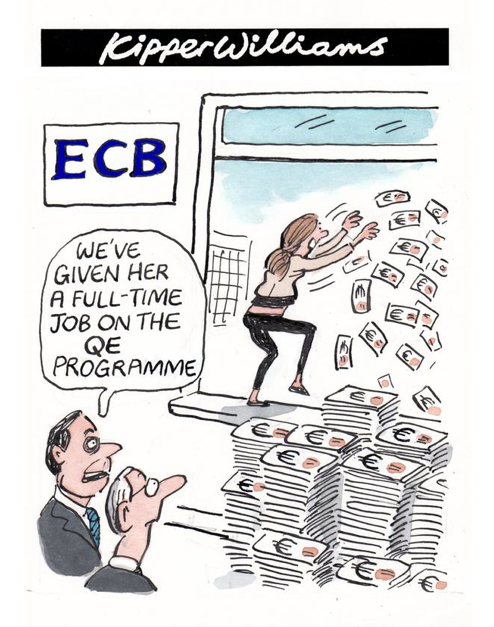

When private financial organizations have too much leverage, their

assets are hurt and they can no longer lend to their peers, leading to

freezing up of credit markets, as a result. However, a public sector

financial institutions

like the European Central Bank operates on another level. The ECB can

print euros that facilitate things. The Central Bank of Greece cannot,

which means Greece is essentially at the mercy of the ECB.

On Monday, the ECB added to pressure on Greece having declined to raise its emergency assistance to Greece and thus making a default more likely. While a Greek default and a possible 'Grexit' would be devastating for the country's economy, it will have little impact on the ECB's ability to lend to other potential trouble spots, like Portugal or Ireland.

This is mainly why Greece will hardly cause substantial volatility in financial markets.

According to Bordo, however, European politics are often incoherent, which creates

uncertainty. The EU does not operate as a "clean" monetary union, like the U.S. or Canada.

It may also turn out that that markets will view a

Grexit as a precursor to the unraveling of the eurozone, as financial

markets may have a delayed reaction. And that would have negative

effects.