High-frequency trading (HFT) is capturing headlines, but this concept is nothing new. Everything is relative, and what’s an intraday swing-trading approach today might have been considered the epitome of trading speed in the 1950s. But while perspectives change, one thing has remained constant. High-frequency trading systems are systemized to better take advantage of the fastest speeds a contemporary market allows.

The history of trading systems predates the general use of computers. Trading systems in the 1920s used chart books, hand drawn or purchased, and/or manual calculations. Charts and data services had their own methods for expediting delivery. Some weekly books were mailed on Thursday, with Friday’s data delivered over the weekend. Others were printed on location at the exchanges, where they could be picked up on Friday evenings. This was the Pony Express version of a logistical edge in the early 20th century.

High-frequency trading (HFT) is capturing headlines, but this concept is nothing new. Everything is relative, and what’s an intraday swing-trading approach today might have been considered the epitome of trading speed in the 1950s. But while perspectives change, one thing has remained constant. High-frequency trading systems are systemized to better take advantage of the fastest speeds a contemporary market allows.

The history of trading systems predates the general use of computers. Trading systems in the 1920s used chart books, hand drawn or purchased, and/or manual calculations. Charts and data services had their own methods for expediting delivery. Some weekly books were mailed on Thursday, with Friday’s data delivered over the weekend. Others were printed on location at the exchanges, where they could be picked up on Friday evenings. This was the Pony Express version of a logistical edge in the early 20th century.

Traders would run these systems manually using graph paper to make their own charts and ledger paper to lay out the rules. Testing these systems was enormously labor intensive. Another tool was to draw charts on glass. These glass-drawn charts would be laid on top of current market action in an effort to find analog years.

Interestingly, many early systems were not all simple systems, such as moving averages. Many were complex pattern-based systems. An example is the Dunnigan One-Way Thrust Method, which systematically identified patterns relating to tops and bottoms within the market. It offered 100% objective rules to identify patterns, which would be used to place buy and sell orders. It came before computers and was done by hand. This system, which sold for $2,000 in 1955 (almost $18,000 in today’s money) was detailed in the November 1998 issue of Futures.

Early systems were complex and not easy to update over time. In fact, much of the work of the 1970s was simplifying many of these systems and their rules to make it easier to follow and track. This simplification also made it easier to use a calculator and, in the future, computers to program these systems.

One of the two most famous systems to evolve from this process was the Turtle System, which gained prominence in the mid-1980s. The system itself was nothing fundamentally new. It was based on a very old system that predated computers: Donchian’s Four-Week Rule. The Turtle System used 20-day and 50-day breakouts with various filters to manage risk and let profits run.

Another early prominent system was Larry Williams’ Volatility Breakout System, which was released in 1982. This was one of the most successful systems for many years.

The idea of this system was to buy some expansion of the current

range, or the last few days’ average of the range added to the opening,

close or some other value. Williams originally sold this system for

$3,000. It was at the heart of his famous winning streak in a public

trading contest in 1987 when he turned $10,000 into more than $1.1

million.

Selling dreams

Although many early trading systems were valid and certainly worked for many traders, several systems had a bad reputation. The thing about traditional trading systems, even completely mechanical ones, is they rely on human interaction. While the system rules can be written in stone, the fear and greed of the person trading the system can interfere. Mistakes are made and trading systems fail. (Of course, no trading system is perfect, and sometimes they just lose money on their own.)

These failures—combined with the unscrupulous individuals who were selling bogus systems—gave trading system vendors a bad name.

There were some success stories, though. Welles Wilder was a pioneer of trading strategies in the 1970s, and his systems were later featured in the popular trading platform CQG. CQG became a premier professional charting service in the early 1980s and, you could say, was the chosen tool of that era’s high-frequency traders. In those days, it cost $1,100 a month to rent the CQG platform. Simply put, you don’t pay those lease rates, especially in 1980 dollars, if you aren’t making money.

“Club 3000” was a newsletter for systematic traders. It was started in 1981 and edited by Bo Thunman. It featured trading system reviews by Thunman as well as reader submissions. The newsletter name itself was a playful jab at a common price tag for trading systems of the day ($3,000); the publication reviewed good and bad systems. It also spawned others that played to the system trader market. In the early 1990s, “Commodity Traders Club News” was founded and edited by David Green. It was a direct competitor to Club 3000. Green also developed the Swing Catcher system. Another influential newsletter over the years has been “Futures Truth,” launched by John Hill.

One interesting trait of traders, high-frequency or low-frequency, is competitiveness. As such, many good friendships go sour when one person decides he can do something better than the next guy, regardless of whether “the next guy” is his best friend.

For the consumer, however, this competitiveness among developers is a

double-edged sword. On one hand, competition encourages excellence. On

the other, it is notoriously easy for a dishonest system developer to

fudge the results—or, say, develop rules that work well in the hands of

professionals but might require too much precision or capital for a

typical retail trader.

Good systems go bad

Larry Williams is one of the most prolific trading education professionals in the industry. He has written countless articles, several books and held numerous seminars, at many of which he has traded his own money and shared profits with the attendees. Williams also came of age in the formative years of the computerized trading systems industry that laid the foundation for today’s high-frequency traders, and he has a learned perspective on the phenomenon.

Williams contends that while there always will be bad apples, for the most part, trading system vendors tried their best to create good systems. A problem bigger than dishonesty, Williams says, is the early developers didn’t understand backtesting and optimization. This isn’t surprising because at this time, such concepts were foreign. Even professional researchers, with doctorates in hard sciences, were making rookie mistakes as early trading system designers.

Parameter selection, optimization surfaces, walk-forward optimization, out-of-sample testing—all of these concepts were either unknown, ignored or applied in such a way that they violated basic mechanics of the markets.

“We were babes in a new-found woods,” Williams says. “Our youth convinced us we could do no wrong, and our brashness made us think that we had figured it all out. In fact, we had a good glimpse, but a lot more to learn.”

Older systems that pre-dated computers were, for the most part, not optimized. Rather, they were developed based on a strong premise. Today, a portfolio-level optimization of multiple variables can still take hours—sometimes days—on an average computer setup. By hand, it would have taken years. As such, early developers had to do more work on the front end, understanding why the systems should work.

Today, it is possible to try millions of combinations of system rules or parameters. Of course, some of them will work brilliantly purely by fluke. Now we know to use statistical tests to determine whether an observed distribution is due to chance. In other words, we test whether the variables are independent and then test whether the observed data are distributed as if they were independent. If the observed data don’t fit the model, it’s more likely that the variables are dependent, invalidating the hypothesis.

Computers and optimization were new to traders in the early days of

system development. Many of these tests were not fully understood or

used in the right way. Even if we were familiar with these tests in

other applications, we didn’t know how to apply them properly to

trading. Many systems designers were not malicious. They had good

intentions but they just simply did not know any better.

Regulatory guidelines

When vendors sold systems in the early days, people didn’t understand the limitations of hypothetical backtesting results. Starting in 1985, the National Futures Association (NFA) required members to post a disclaimer on system results. This has been updated over the years.

Here’s a sample:

HYPOTHETICAL PERFORMANCE RESULTS HAVE MANY INHERENT LIMITATIONS, SOME OF WHICH ARE DESCRIBED BELOW. NO REPRESENTATION IS BEING MADE THAT ANY ACCOUNT WILL OR IS LIKELY TO ACHIEVE PROFITS OR LOSSES SIMILAR TO THOSE SHOWN. IN FACT, THERE ARE FREQUENTLY SHARP DIFFERENCES BETWEEN HYPOTHETICAL PERFORMANCE RESULTS AND THE ACTUAL RESULTS SUBSEQUENTLY ACHIEVED BY ANY PARTICULAR TRADING PROGRAM.

ONE OF THE LIMITATIONS OF HYPOTHETICAL PERFORMANCE RESULTS IS THAT THEY ARE GENERALLY PREPARED WITH THE BENEFIT OF HINDSIGHT. IN ADDITION, HYPOTHETICAL TRADING DOES NOT INVOLVE FINANCIAL RISK, AND NO HYPOTHETICAL TRADING RECORD CAN COMPLETELY ACCOUNT FOR THE IMPACT OF FINANCIAL RISK IN ACTUAL TRADING.

Although well-intentioned, these rules have their downside. For example, assume a trading system that has lost money the last 20 years starts making money trading real money. While the recent profitable results might be the outlier, they rather than the 20 years of research would carry more weight in the eyes of the regulator. Indeed, clients may have no idea how poorly the system performed in the past because of reporting limitations. Because of this, many vendors do not register with the NFA so they can show both complete backtests as well as actual results.

Hypothetical results have their problems, too, of course. Among them are:

- Problems due to data and how it affects real trading.

- Problems due to hypothetical slippage and fills.

- Problems due to hindsight.

- Problems due to human error.

These issues are not trivial, and exploring them in depth is beyond the scope of this article. However, to broaden our understanding of the environment that bred today’s high-frequency traders, let’s explore them briefly.

Data issues are critical. There is data cleanliness, of course, but also how data are rolled from one finite futures contract to another. Rollovers can vary results on a single market by as much as 30%. Rolling based on a fixed date prior to expiration, rather than volume, works most consistently. With respect to fills and slippage, electronic markets have reduced slippage significantly, but it remains an issue, particularly for today’s extremely fast, tick-level trading strategies where a tick here and a tick there can turn a big winning system into a lemon.

Human error is always an issue. It’s extremely difficult to continue trading a system through an extended drawdown, especially if you didn’t develop that system. Often, buyers believe that a system is a guaranteed win all the time. This is false. Every trading system has drawdowns.

Auto execution

If you aren’t following the rules of the system, you are not systematically trading; you are trading discretionarily. This was, and remains, an issue for part-time traders. For this reason, Robbins Trading created a service known as System Assist in the 1980s. In short, brokers simply traded the systems on behalf of the clients.

There are many ways brokers control accounts. Guided accounts rely on a limited power of attorney. The client decides what to trade and the quantity, but the buy and sell decisions are made by the broker. Because the broker is not acting as a commodity trading advisor (CTA), results do not need to be shown. A CTA, on the other hand, has full control over the account, including size, trade decisions, etc. CTAs are NFA members and need to be registered. They also are required to fully disclose results.

System Assist was developed so people could manage their own money. The client picked the system, quantity and what to trade.

Other brokers, such as Striker, Capital Trading Group in Chicago and Daniels Trading, offer similar services.

These tools and others have provided the foundation for where we are today. That said, the evolutionary process has indeed diverged, with the retail automated system trading market becoming something entirely different than the second-long trades that have come to represent what typically is referred to as high-frequency trading.

However, those high-frequency strategies would not have been possible

unless expert traders had taken the technology there, launched from the

humble beginnings of the chart book and graph paper of previous

generations.

Tracking trading systems

In the early years of my trading career, I purchased a number of trading systems that turned out to not live up to their billing.

A prominent vendor copied two pages out of a book that I published, where I discussed a trading tool, not a system. He sold it as a system and claimed it was the best thing he ever developed. At this stage (prior to organizing Futures Truth), I had hired a computer programmer, John Fisher, who had worked for the Department of Defense on the design of the Tomahawk cruise missile guidance system.

In 1988, with my experience as a professional trader and John Fisher’s programming abilities, we developed historical backtesting software. After that, I organized Futures Truth to bring truth and honesty to the trading world.

George Pruitt, a computer science graduate, came on board in 1989 and helped finalize the software, which became known as Excalibur. Initially, we were using it just to reveal fraudulent systems. However, people with good methodologies wanted their systems to be monitored and ranked. We always have had an arm’s-length relationship with our system vendors and have never charged a tracking fee. Quite a few fraudulent vendors were put out of business because the numbers that were reported simply did not measure up to the hype.

Today, we track more than 200 publicly offered trading systems and report walk-forward results in our quarterly publication.

Some early vendors who were in Futures Truth included:

- Doug Bry, TTS-VBS System

- Bruce Babcock, many systems

- Welles Wilder, systems from his “New Concepts in Technical Trading Systems”

- Essex Trading Co., Tradex21

- Lou Mendehlson, Profit Taker

- Bob Pardo, numerous systems

- John Ehlers, Mesa Software

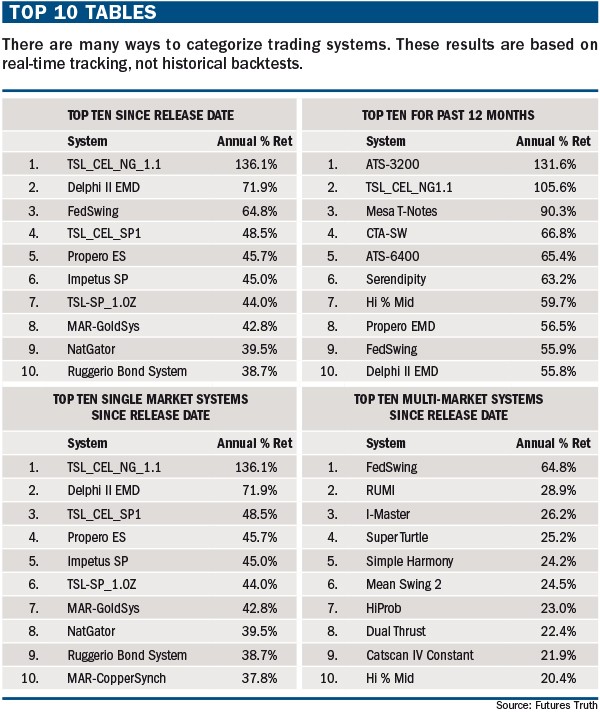

Futures Truth offers results from when the system is released (see “Top 10 tables,” below”). These are hypothetical, but Futures Truth does not rely on hindsight.

One issue about trading systems is consistency. If you look at the top trading systems over time, you will see that most systems don’t spend much time on the top list. Over the years, certain system vendors consistently have ranked in the top 10. Many do offer more than one system, but it seems like one or two of their best systems are the ones that make the list.

For years, trend-followers dominated this list, but recently shorter-term and day-trading systems have crept in. Most of these follow only the stock indexes. Trend-following will probably work its way back and those vendors that made their systems adaptive have either weathered the storm or have already started to recover.