5 outstanding people who predicted Greek crisis years before it actually happened

Greece had a tough time making it into the euro in the first place. The country failed to qualify for the single currency in 1998 before being granted admission in 2001. And there were people who predicted it will be a further failure, ahead of their time. Here they are:

Margaret Thatcher

Back in 1990, as The Telegraph informed us referring to her autobiography, the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom warned that the single currency could not accommodate stronger and weaker economies. Here she is describing arguments with John Major about the topic:

We had arguments which might persuade both the Germans — who would be worried about the weakening of anti-inflation policies — and the poorer countries — who must be told that they would not be bailed out of the consequences of a single currency, which would therefore devastate their inefficient economies.

Wynne Godley

In a 1992 article for the London Review of Books, the British economist wrote:

What

happens if a whole country - a potential ‘region’ in a fully integrated

community - suffers a structural setback? So long as it is a sovereign

state, it can devalue its currency. It can then trade successfully at

full employment provided its people accept the necessary cut in their

real incomes. With an economic and monetary union, this recourse is

obviously barred, and its prospect is grave indeed unless federal

budgeting arrangements are made which fulfil a redistributive role.

If a country or region has no power to devalue, and if it is not the beneficiary of a system of fiscal equalisation, then there is nothing to stop it suffering a process of cumulative and terminal decline leading, in the end, to emigration as the only alternative to poverty or starvation.

Arnulf Baring

In his 1997 book "Scheitert Deutschland?", the German political scientist warned about the way German people will be treated in case of a single currency crisis.

They will say that we are subsidizing scroungers, lounging in cafés on the Mediterranean beaches. Monetary union, in the end, will result in a gigantic blackmailing operation. When we Germans demand monetary discipline, other countries will blame their financial woes on that same discipline, and by extension, on us. More, they will perceive us as a kind of economic policeman. We risk once again becoming the most hated in Europe.

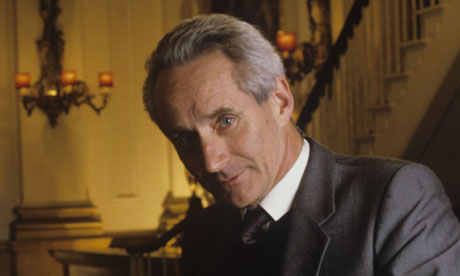

Randall Wray

This economist was critical of the structure of the euro zone in his 1998 book, "Understanding Modern Money".

Under

the EMU, monetary policy is supposed to be divorced from fiscal policy,

with a great degree of monetary policy independence in order to focus

on the primary objective of price stability. Fiscal policy, in turn will

be tightly constrained by criteria which dictate maximum deficit-to-GDP

and debt-to-deficit ratios. Most importantly, as Goodhart recognizes,

this will be the world’s first modern experiment on a wide scale that

would attempt to break the link between a government and its currency.

As currently designed, the EMU will have a central bank (the ECB) but it will not have any fiscal branch. This would be much like a US which operated with a Fed, but with only individual state treasuries. It will be as if each EMU member country were to attempt to operate fiscal policy in a foreign currency; deficit spending will require borrowing in that foreign currency according to the dictates of private markets.

Mathew Forstater

In his 1999 article for the Eastern Economic Journal, the economist expressed concerns for the future of the single currency:

Under

the EMU, if investors are at all hesitant about any one member’s debt,

they can buy another member’s debt without incurring currency risk,

since there is no exchange rate variability among the currencies of

member countries. Because member nations now are dependent on investors

for funding their expenditure, failure to attract investors results in

an inability to spend. Furthermore, should a member’s revenues fail to

keep pace with expenditures due to an economic slowdown, investors will

likely demand a budget that is balanced, most likely through spending

cuts. In other words, market forces can demand pro-cyclical

fiscal policy during a recession, compounding recessionary influences.

Even if there were no imposed limits on countries’ deficits and national debts, the structure of the EMU makes it nearly impossible for a country to enact a counter-cyclical fiscal policy even if there were the political will. This is because, by giving up their national monetary sovereignty, countries are no longer able to conduct coordinated fiscal and monetary policy, essential for a comprehensive and effective remedy to periodic demand crises. Why would countries voluntarily sacrifice the ability to conduct a coordinated macroeconomic policy, especially at a time when official unemployment rates are in double digits and there are clear deflationary pressures?