What's going on with the global economy? These five charts explain

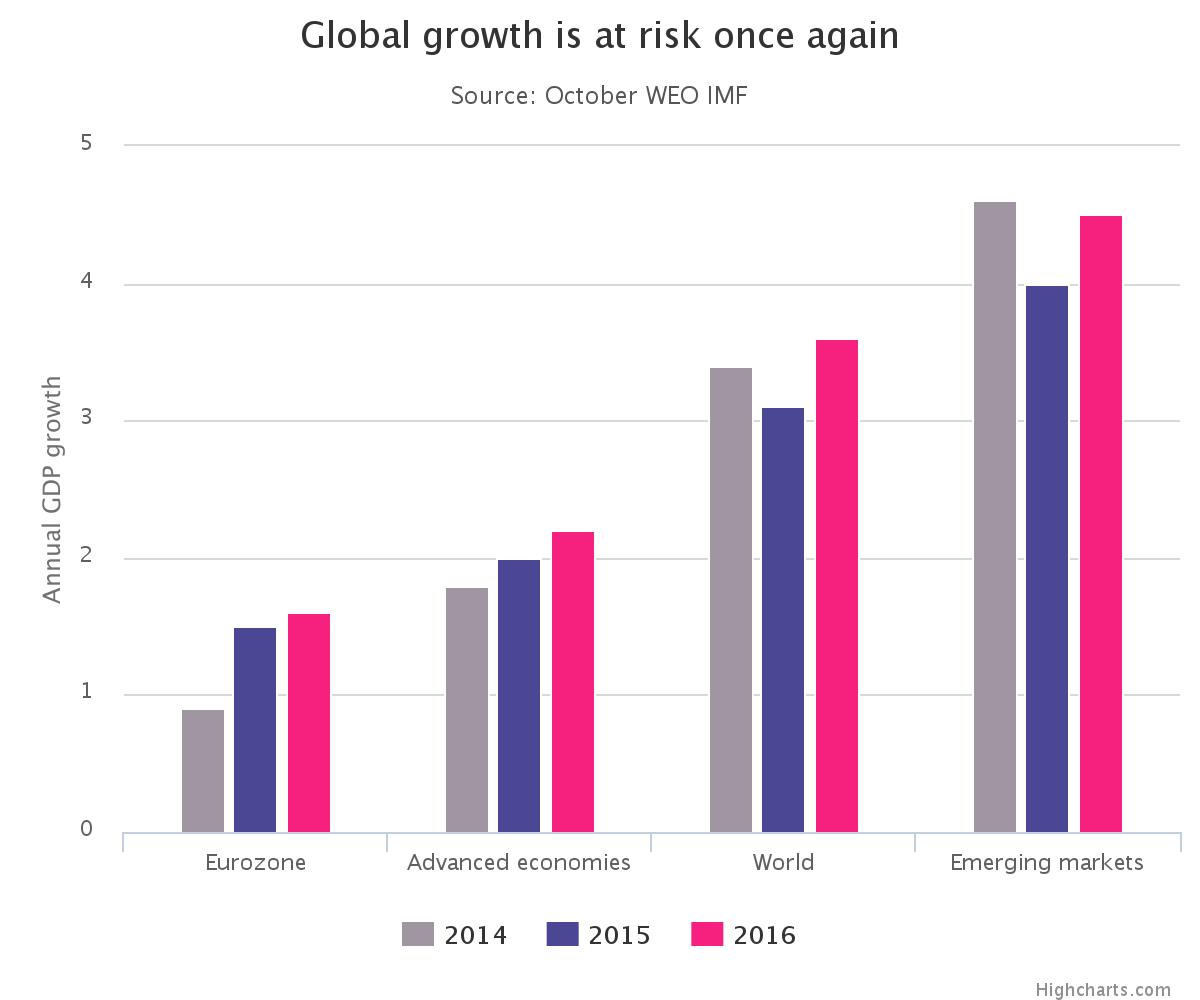

Yesterday the International Monetary Fund slashed its global economic forecast. Again.

In its fresh World Economic Outlook (WEO) the international institution predicted growth will fall to its lowest level since the onset of the

financial crisis, forecasting a slowdown of 3.1% this year,

recovering slightly to 3.6% next year.

Three main factors affect most of all: China's rebalancing act, Fed's interest rate lift-off and plunging commodity prices.

There has been much talk of the U.S. and U.K. rate increase recently. But approaching rate hikes in these countries are not a sign that central banks are prepared to stop propping up the world just yet, which should remain in place, the IMF says.

"Accommodative monetary policy continues to be essential, alongside macroprudential tools to contain financial sector risks," said the international body.

According to its forecasts, both Europe and Japan are set to see below-target inflation for the next five years. The Fund is now urging the eurozone to redouble its monetary firepower with a longer QE that will also widen the kind of assets the ECB can buy.

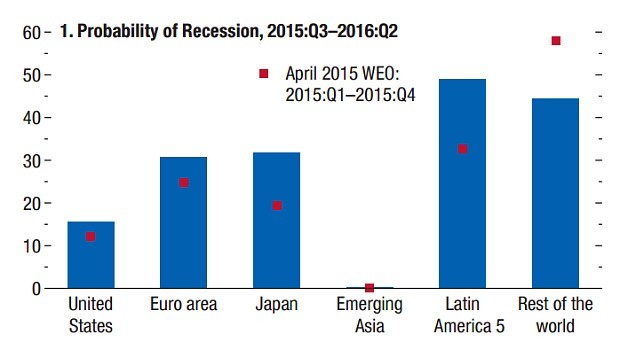

Latin America is currently the most economically depressed region.

The possibility of a recession hitting the continent is now 50%, up from around 35% just six months ago.

The region's fortunes are being pressed lower by its biggest economy Brazil, which will now fall into a -3% recession this year, followed by a 1% contraction in 2016.

This is the fifth year in a row the IMF has had to revise down its growth estimates for the emerging world as a whole.

The Fund's research division has admitted before that its consistent over-estimation of developing world GDP has contributed to its forecasts missing the mark over the last five years.

Do recessions have a permanent, damaging impact on future growth?

That was another question the IMF addressed.

Olivier Blanchard, the Fund's ex chief economist, studied the 122 recessions in 23 advanced economies over the last 60 years. Blanchard et al. found over half of recessions were followed by lower output growth than that seen before the downturn struck.

Academics are divided about the potential causes of these

post-recession drops. However, they refer to developments such as changes to

financial institutions - such as tighter bank lending rules - and the

phenomenon of long-term unemployed people dropping out of the workforce,

as probable contributing factors.

The chart below shows the striking degree to which growth in the

euro area has failed to take off in the wake of The Great Recession.

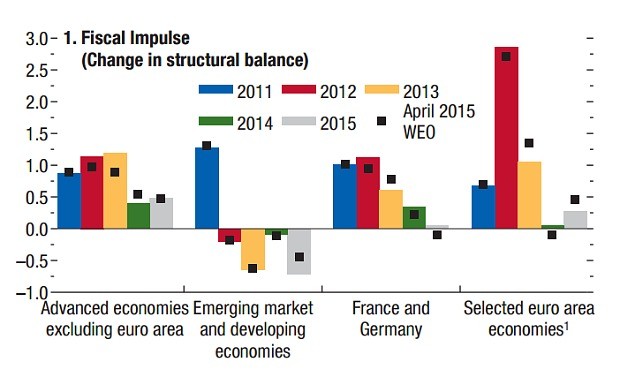

Austerity is associated with recovery from crisis, and there is currently less austerity in the world.

One of the main topics for advanced world economies, as they sought to reduce their debt and deficit after the onset of the crisis, was austerity. The fund has been the world's biggest lobbyist for fiscal discipline since it was founded in the post-war era.

But the pace of this tightening is on course to moderate as sluggish growth prospects trigger governments to ease fiscal policy and buoy growth.

The euro area is a big exception to that rule, as over there the belt-tightening is set to more than triple from 2014. According to the IMF, it is the euro's two biggest economies - France and Germany - where fiscal discipline is about to be higher than estimated in April.

The graph below indicates the extent to which the

developed world governments have carried out fiscal consolidation

compared to their peers (see the eurozone in 2012 in particular):