- Statistics, optimisation and "lucky coin" ....

- Probability, how do you turn it into a pattern ...?

- Machine learning in trading: theory, models, practice and algo-trading

Suppose we see some interesting feature on the chart and assume that it is a pattern that can be used to make a profitable Expert Advisor. So, if an Expert Advisor that uses this expected pattern shows profit without any optimization when tested on a long timeframe, we can consider it to be a real pattern with a high probability.

In my view, there is a spectrum of regularities that I would identify somehow.

Let's assume that you have a history of the intensity of the factor (let's call it F1), which causes quite a natural price change. You need to filter the price history so that it clearly correlates to the history of that factor after filtering (by the filter that we denote by C1). Then the price that will be filtered by C1 will give you a picture of its regular movement C1, associated with the action of F1.

Determine all other factors important for pricing (Ф2, ..., Фn) and find their corresponding filters (С2, ..., Сn), which will give a spectrum of regular price movements (Ц1, ..., Цn).

It's foolish to look for a pattern at random. Any regularity must be based on a theory, justified by the logic of the course of the processes or assumptions based on the analysis of observation results, or on a plausible postulate. Therefore, any regularity has to be searched for consciously, with the approximate expectation of how it should appear. Consequently, the search for a pattern is painstaking and exhausting work and should begin with the formulation of the above-mentioned positions. During last almost 8 years of searching I managed to formulate only 3 assumptions in which I managed to find 3 regularities that led to positive results. But all of them confirmed my assumption that in such a perfect market as Forex it is impossible to achieve outstanding results. Profits fluctuate between 10 and 15 per cent per annum, and that is when they are compounded over 10-20 years. It is not even possible to guarantee a profit within these limits for a specific, taken at random, year in history. Conclusion - it is impossible in principle to get a stable and guaranteed profit on the market, which is much bigger than that of a bank, because Forex is first of all an interbank instrument. On the other hand, this is my personal opinion and by no means am I imposing it on other market researchers and rake-evaluators. I wish them luck in finding better results.

And the very 3 theories I have developed and researched are known to all:

1. The Universal Regression Model for predicting market price https://www.mql5.com/ru/articles/250;

2. market theory https://www.mql5.com/ru/articles/1825;

3. bull and bear strength analysis https://www.mql5.com/ru/code/19139 ,https://www.mql5.com/ru/code/19142.

- www.mql5.com

A recent article of mine has a similar one - exploring the deviation of price from random wandering after gaps.

A recent article of mine has a similar one - exploring the deviation of price from a random walk after gaps.

Alexey, excellent article in line with the pattern search problem, especially the sober conclusion about insignificant profit, which coincides with my conclusions. Let's look for new directions in this journey. Thanks for the link.

A recent article of mine has a similar one - exploring the deviation of the price from randomly wandering after gaps.

Alexei. Thank you, I have read it already and got acquainted with the results and methods, as well as your previous article with risk estimation.

Especially I am close to your described method of random walk of price, because in my question (post) I mean exactly this feature.

But to apply your method as a stencil to the decision of the problem, I do not think, both fundamentally and in applied experience, I am not so strongly savvy as you, that reliably and quickly to solve this problem.

Tell me Alexey, if I provide you with an algorithm that I believe creates a 50/50% probability of event guessing, will you evaluate its credibility or unreliability?

My algorithm for finding a price works on the principle of a theorvert, but it ensures repeatability of the outcome in the entire sample of history, as well as in some parts of it.

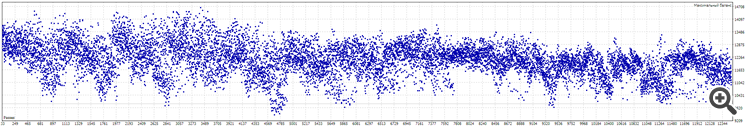

It looks like this:

The algorithm has only three variables SL, TP and Market Entry Point.

I set a certain range of values for each of these variables to dissolve/average the influence of fitting.

SL from 40 to 70

TP from 40 to 70

Market entry point from 0 to 12.

Total of 12 493 variables.

Test results on the history of 10 years:

Task.

Identify/prove: Is this result purely a fit or is there an algorithm where the probability of random, independent outcomes may be greater than 50/50.

Alexey. Will you do it?

I am skeptical to my results, i suppose they were caused by mistake in code or logical conditions, but since full week i can't find neither one or the other.

Help... And the diamond of your generosity will shine in the setting of my gratitude)

Suppose we see some interesting feature on a chart and assume that it is a regularity and it can be used to make a profitable Expert Advisor. So, if an Expert Advisor that uses this expected pattern shows profit without any optimization when tested on a long timeframe, we can consider it to be a real pattern with high probability.

Well this method is clear to me, but it does not reliably prove it, it only creates probability prerequisites... more/less.

Thanks anyway)

I was suddenly reminded of Plato's definition of what a human being is:

The disciples of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato were once asked to define man, to which he replied:

"Man is an animal with two legs and no feathers." However, after Diogenes of Sinop..,

Diogenes of Sinop brought a plucked rooster to the Academy and presented it as Plato's man,

Plato had to add to his definition: 'And with flat fingernails'.

)))

To find out if it's a fit or not, check on the forward

I should try it... But I don't really understand the usefulness of Forward.

If I understand correctly, then forwarding will take some part of history and run an additional run on it...

But if I'm already using all (quality) history in the test, is there any sense in running forward?

I should try it... But I don't really understand the usefulness of Forward.

If I understand correctly, then forwarding will take some part of history and run an additional run on it...

But if I'm already in the test using the whole (quality) history, then is it worth forward?

If the strategy's profitability is preserved on the forward, then we have found a pattern, if not, then it is just fitting to the history.

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use