Thanks for the article!

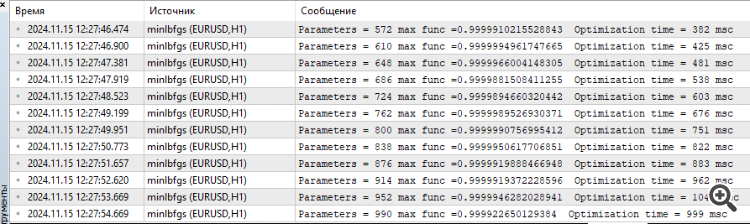

I sat for a while yesterday and today on the Hilly function and alglib methods. Here are my thoughts.

In order to find the maximum of this function, especially when the number of parameters is 10 and more, it is pointless to apply gradient methods, this is the task of combinatorial methods of optimisation. Gradient methods just instantly get stuck in the local extremum. And it does not matter how many times to restart from a new point of the parameter space, the chance to get to the right region of space from which the gradient method instantly finds a solution tends to zero as the number of parameters increases.

For example, the point of space from which lbfgs or CG for 2(two) iterations find the maximum for any number of parameters is {x = -1,2 , y = 0.5}.

But the chance to get into this region as I have already said is simply zero. It must be a hundred years to generate random numbers.

Therefore, it is necessary to somehow combine the genetic algorithms presented in the article (so that they could do reconnaissance and reduce the search space) with gradient methods that would quickly find the extremum from a more favourable point.

Thank you for your feedback.

In order to find the maximum of a given function, especially when the number of parameters is 10 or more, it is pointless to use gradient methods.

Yes, that's right.

This is the task of combinatorial methods of optimisation.

Combinatorial methods, such as the classical "ant", are designed for problems like the "travelling salesman problem" and the "knapsack problem", i.e. they are designed for discrete problems with a fixed step (graph edge). For multidimensional "continuous" problems, these algorithms are not designed at all, for example, for tasks such as training neural networks. Yes, combinatorial properties are very useful for stochastic heuristic methods, but they are not the only and sufficient property for successful solution of such near-real test problems. The search strategies themselves in the algo are also important.

Gradient-based ones simply get stuck in a local extremum instantly. And it doesn't matter how many times to restart from a new point of the parameter space, the chance to get to the right region of the space from which the gradient method instantly finds a solution tends to zero as the number of parameters increases.

Yes, it does.

But the chance to get to this region, as I have already said, is simply zero. It would take about a hundred years to generate random numbers.

Yes, that's right. In low-dimensional spaces (1-2) it is very easy to get into the vicinity of the global, simple random generators can even work for this. But everything changes completely when the dimensionality of the problem grows, here search properties of algorithms start to play an important role, not Mistress Luck.

So we need to somehow combine genetic algorithms presented in the article (that they would do exploration, reduce the search space) with gradient methods, which would then quickly find the extremum from a more favourable point.

"genetic" - you probably mean "heuristic". Why "the fish needs an umbrella" and "why do we need a blacksmith? We don't need a blacksmith.")))) There are efficient ways to solve complex multidimensional in continuous space problems, which are described in articles on population methods. And for classical gradient problems there are their own tasks - one-dimensional analytically determinable problems (in this they have no equal, there will be fast and exact convergence).

And, question, what are your impressions of the speed of heuristics?

SZY:

Oh, how many wonderful discoveries

Prepare the spirit of enlightenment

And experience, the son of errors,

And genius, the friend of paradoxes,

And chance, God's inventor.

ZZZY. One moment. In an unknown space of search it is never possible to know at any moment of time or step of iteration that it is actually a really promising direction towards the global. Therefore, it is impossible to scout first and refine later. Only whole search strategies can work, they either work well or poorly. Everyone chooses the degree of "goodness" and "suitability for the task" himself, for this purpose a rating table is kept to choose an algorithm according to the specifics of the task.

Yes, that's right. In low-dimensional spaces (1-2) it is very easy to get into the neighbourhood of a global, simple random generators can even be useful for this. But everything changes completely when the dimensionality of the problem grows, here search properties of algorithms, not Lady Luck, start to play an important role.

So they fail

And, question, what are your impressions of the speed of heuristics?

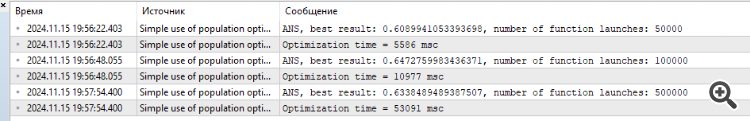

Despite the fact that they work fast. The result for 1000 parameters something about 0.4.

That's why I intuitively thought that it makes sense to combine GA and gradient methods to get to the maximum. Otherwise, separately they will not solve your function. I haven't tested it in practice.

P.S. I still think that this function is too thick, in real tasks (training of neural networks, for example) there are no such problems, although there too the error surface is all in local minima.

1. They're not doing a good job

2. even though they work fast. The result for 1000 parameters is something around 0.4.

3. That's why I intuitively thought that it makes sense to combine GA and gradient methods to get to the maximum. Otherwise, separately they won't solve your function. I haven't tested it in practice.

4. P.S. I still think that this function is too thick, in real tasks (training of neural networks, for example) there are no such problems, although there too the error surface is all in local minima.

1. What do you mean "they can't cope"? There is a limit on the number of accesses to the target function, the one who showed a better result is the one who can't cope)). Should we increase the number of allowed accesses? Well, then the more agile and adapted to complex functions will come to the finish line anyway. Try to increase the number of references, the picture will not change.

2. Yes. And some have 0.3, and others 0.2, and others 0.001. Better are those who showed 0.4.

3. It won't help, intuitively hundreds of combinations and variations have been tried and re-tried. Better is the one that shows better results for a given number of epochs (iterations). Increase the number of references to the target, see which one reaches the finish line first.

4. If there are leaders on difficult tasks, do you think that on easy tasks leaders will show worse results than outsiders? This is not the case, to put it mildly. I am working on a more "simple" but realistic task of grid training. I will share the results as always. It will be interesting.

Just experiment, try different algorithms, different tasks, don't get stuck on one thing. I have tried to provide all the tools for this.

1. What do you mean "fail"? There is a limit on the number of accesses to the target function, the one who has shown the best result is the one who can't cope)). Should we increase the number of allowed accesses? Well, then the more agile and adapted to complex functions will come to the finish line anyway. Try increasing the number of references, the picture will not change.

2. Yes. And some have 0.3, and others 0.2, and others 0.001. Better are those who showed 0.4.

3. It won't help, intuitively hundreds of combinations and variations have been tried and re-tried. Better is the one that shows better results for a given number of epochs (iterations). Increase the number of references to the target, see which one reaches the finish line first.

4. If there are leaders on difficult tasks, do you think that on easy tasks leaders will show worse results than outsiders? This is not the case, to put it mildly. I am working on a more "simple" but realistic task of grid training. I will share the results as always. It will be interesting.

Just experiment, try different algorithms, different tasks, don't fixate on one thing. I have tried to provide all the tools for this.

I am experimenting,

About the realistic task it is right to test algorithms on tasks close to combat.

It's doubly interesting to see how genetic networks will be trained.

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use

Check out the new article: Atomic Orbital Search (AOS) algorithm: Modification.

In the second part of the article, we will focus on modifying the AOS algorithm, since we cannot pass by such an outstanding idea without trying to improve it. We will analyze the concept of improving the algorithm, paying special attention to the specific operators that are inherent to this method and can improve its efficiency and adaptability.

Working on the AOS algorithm has opened up many interesting aspects for me regarding its methods of searching the solution space. During the research, I also came up with a number of ideas on how this interesting algorithm could be improved. In particular, I focused on reworking existing methods that can improve the performance of the algorithm by improving its ability to explore complex solution spaces. We will consider how these improvements can be integrated into the existing structure of the AOS algorithm to make it an even more powerful tool for solving optimization problems. Thus, our goal is not only to analyze existing mechanisms, but also to propose other approaches that can significantly expand the capabilities of the AOS algorithm.

Author: Andrey Dik