so many manipulation story's to hear and read

where does one find the time to fit them all in

hope shes very careful crossing the road from now on

so many manipulation story's to hear and read

where does one find the time to fit them all in

hope shes very careful crossing the road from now onWhich road?

The poor woman is not going to get a decent job from now till the end of her life. No need for a roads.

This ends the road :

In her ruling on Wednesday, Abrams also rejected a move by Stengle for greater disclosure by the judge about her husband's relationship with Goldman Sachs. Abrams disclosed on April 3 that she had just learned that her husband, Greg Andres, a partner at Davis Polk & Wardwell, was representing Goldman in an advisory capacity.

Stengle said at the time she would not seek Abrams' recusal, the judge said, and went ahead the next day with scheduled oral arguments on the defendants' bid to dismiss the case.

But on April 11, Stengle made a written request for a "more complete disclosure" of Andres' relationship with Goldman, and Abrams' own working relationship with another defense lawyer.

Abrams said that was too late, given that Segarra by then would have had a chance to "sample the temper of the court" and perhaps anticipate she would lose unless Abrams recused herself. "The timing of plaintiff's requests suggests that she is engaging in precisely the type of 'judge-shopping' the 2nd Circuit has cautioned against," Abrams wrote, referring to the federal appeals court in New York. "Such an attempt to engage in judicial game-playing strikes at the core of our legal system."

Ridiculous ...

Regulators deferred to Goldman Sachs

Secret tapes made by a banking investigator examining Goldman Sachs show a culture of deference and risk aversion in which regulators were afraid to anger the very financial institutions they were supposed to be overseeing.

The 46 hours of recordings of meetings and conversations come from Carmen Segarra, a Harvard-trained lawyer who was hired in 2011 by the New York Federal Reserve as part of a team overhauling how the banking system was regulated after the 2008 financial crisis.

Segarra found a culture in which regulators were cozy with the banks they worked with and where managers were loath to say or do anything that might upset them. Goldman Sachs and the New York Fed have denied Segarra's allegations.

The tapes were released Friday as part of a joint report by National Public Radio's "This American Life" show and the non-profit investigative journalism organization proPublica.

In one example, the New York Fed team was concerned about a deal Goldman Sachs was doing with a Spanish bank called Banco Santander. Her boss, Michael Silva, termed it "legal but shady."

But before the team met with Goldman Sachs staff, the Fed's staff did not press on the deal. In a discussion afterward, one of the other examiners says on the tape that they didn't want to push the bank too hard. Instead, they could say something like "Don't mistake our inquisitiveness, and our desire to understand more about the marketplace in general, as a criticism of you as a firm necessarily."

Segarra was fired after seven months on the job, because she wouldn't go along with the status quo--and because she wouldn't back down from her assertion that Goldman Sachs didn't have a policy for dealing with conflicts of interest.

She then sued, saying she was being retaliated against for her negative findings against Goldman Sachs. The case was thrown out of court last year when the judge said the facts didn't fit the statute Segarra had sued under.

Her hiring came about in part because of a report written by a David Beim, a former Wall Street banker himself, who was hired as an independent investigator by the New York Fed to look at whether the regulatory agency was neutral and objective.

His 2009 report found exactly the same failings the Segarra tapes show.

See how they bought the judge. No wonder that they are telling that rich people are above the law

The Goldman Tapes And Why The Delusion Of Macro-Prudential Regulation Means The Next Crash Is Nigh

There is nothing like the release of secret tape recordings to clarify an inconclusive debate. I recall that happening with Nixon back in the day. Even as a Washington apprentice I could see that he was a ruthless, power hungry abuser of his office, but much of official Washington just denied it. Then came the tapes. Soon there was no doubt. In short order Nixon was gone.

So now comes the Goldman tapes—-46 hours of recordings by an embedded New York Fed regulator at Goldman Sachs who got fired for attempting to, well, regulate. Would that the Carmen Segarra affair generates a Nixonian result—-that is, exposure that “regulatory capture” is an endemic, potent and inextricable evil that can’t be remediated in situ.

Never mind that what Ms. Segarra was attempting to regulate–whether Goldman had a conflict of interest policy with respect to its M&A clients—-was actually none of the state’s business in the first place. If in the instant case GS was giving squinty eyed advise to its client, El Paso Corporation, because it owned a $4 billion position in the other party to the transaction, Kinder Morgan, so be it. Either the conflict was harmless or eventually Goldman’s M&A business would have been punished by the marketplace—–even stupid executives and boards wouldn’t pay huge fees to be taken to the cleaners for long.

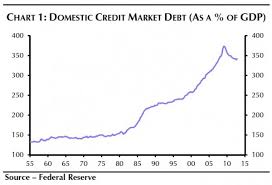

Actually, what the tapes really show is that the Fed’s latest policy contraption—-macro-prudential regulation through a financial stability committee—-is just a useless exercise in CYA. Apparently, even the colony of the bubble blind which inhabits the Eccles Building has started to get nervous about financial bubbles and instability in recent months. What with junk bond yields sporting a 5 handle, the Russell 2000 trading at 80X reported profits and the IPO market having gone full-tilt manic with last week’s pricing at 27X sales of a Chinese e-commerce mass merchant that is a pure proxy for the greatest credit fueled house of cards in human history—-it needed to show some gesture of concern.

Now, it might have gone straight to the horse’s mouth. It might have asked about 70 consecutive months of zero money market rates, for instance, and the manner in which that has enabled speculators to mount massive momentum trades everywhere in the financial markets by funding any “risk asset” that generates a yield or a short-run gain with nearly zero cost options or repo. Or it might have inquired about the destruction of the market’s natural internal mechanisms of stability and financial restraint—-that is, short sellers and two way trading—that has resulted from the Greenspan/Bernanke/Yellen Put; or it might have wondered whether its bald-faced doctrine of “wealth effects” and ever rising stock prices does not in itself create a massive bias toward speculative risking taking and a blind buy-the-dips herd mentality in the casino.

But that would have been inconvenient because it would mean an abrupt end to its labor market focused policy of “accommodation” and a violent hissy fit in the casino. So Yellen and here Keynesian compatriots have invented out of whole cloth a method to drive the wildly vibrating Wall Street financial jalopy with both feet to the floor. That is, on the monetary “policy” side they intend to perpetuate ZIRP for at least another 9 months and near-ZIRP as far as the eye can see , while at the same time interposing in today’s frothy financial markets a Stanley Fischer led posse of regulators to keep speculator exuberance within safe boundaries.

At this point it is not clear which part of the Fed’s “macro-pru” initiative is the more preposterous. Why would you think that a system which required only 9 months to fire Carmen Segarra for comparatively trivial meddling in Goldman’s M&A department is capable of bubble prevention when we are talking about trillions of inflated value in the stock, bond, derivatives and real estate markets? Or that putting a proven serial bubble generator—-that’s essentially what Fischer accomplished during his stint as head of Israel’s central bank—at the head of the financial stability committee would produce, well, financial stability?

It should be evident by now that regulatory capture and the inherent capacity of the marketplace to evade bureaucratic rules, edicts and embedded supervisors mean that “macro-pru” is a crock—an excuse to prolong a dangerous monetary experiment that is inexorably fueling a giant financial bubble and the crash which must inevitably follow.

Take the soaring issuance of sub-prime auto credit, for example, which now accounts for a record 30% of car loans and is putting people in cars at 130% loan-to-value ratios—-borrowers that have no hope of avoiding the repo man a few months down the road. On the margin, nearly all of this explosive growth is being funded in the non-bank market. That is, by freshly minted sub-prime auto lenders who have been given a sliver of equity by LBO houses and a ton of debt by the high yield market. Who is Stanley Fischer going to crack down upon—–the LBO houses creating these fly-by-night lenders, the Wall Street underwriters lead by Goldman who are distributing the junk or Bill Gross’s yield-parched successors at PIMCO and its mutual fund competitors who are buying the stuff?

OK, Stanley Fischer being from MIT, the IMF, Citibank, the Bank of Israel—and to say nothing of his long ago supervision of Ben Bernanke’s PhD thesis which merely Xeroxed Milton Friedman’s false claim that the Fed’s failure to engage in massive QE during 1930-1932 caused the Great Depression—-is too sophisticated to say “no auto junk, period”. What his committee will likely do is issue guidance about keeping debt-to-EBITDA ratios “prudent” at some notional leverage of say 6-8X when these newly minted auto junk yards are issuing the same.

But that’s before the underwriters parade in with a host of complications embedded in “adjusted EBITDA” to account for the fact that two fly-by-night subprime lenders, for example, just merged and therefore need a pro forma adjustment for down-the-road synergy savings; or that a newly minted lender is still scaling up its volume and that on a last month’s run-rate basis, its adjusted EBITDA ratio is 7.8X, not the 16X ratio embedded in its actual GAAP results.

And that doesn’t even account for the fact that the loan books of these start-up auto sub-primes are inherently unseasoned. It does take some time for an assistant night shift manager at a McDonald’s to become the subject of a “restructuring” initiative by the local franchisee and to subsequently default on his car loan. Indeed, the Fischer committee would even be up against the inherently vexing math of a rapidly ramping loan book. That is, while the denominator of loans issued is soaring, the numerator of delinquencies is still lagging. So loan loss reserves are invariably understated during the final blow-off stage of a financial bubble, meaning that earnings and EBITDA are over-stated and hidden leverage risk is rampant. The evidence is there in spades in the wreckage of the LBO and high yield markets during 20009-2010.

In short, even assuming that the obsequious culture of accommodation at the New York Fed so evident in the Goldman tapes could be uprooted, macro-pru is inherently impotent because of information asymmetry. What the Austrian thinkers 100 years ago said about socialism in general is true in spades with respect to the gambling casinos created by the Keynesian money printers. Without honest market prices in the trading pits and at loan desks and underwriting syndicates, financial booms and busts are inevitable, and the state’s regulators and supervisors are hopelessly at sea because they cannot hope to gather and process enough information to stymie the army of speculators chasing false prices with cheap credit.

Or to take another example, what is the Fischer committee going to do about leveraged stock buybacks? Not only is this fueling the speculative rise in the stock averages and the illusion that earnings are growing, when in fact it is only the share count which is shrinking, but it is also adding to the dangerous build-up of corporate debt that will become hugely problematic when interest rates are finally allowed to normalize.

But imagine the utter hissy fit that would instantly arise on Wall Street if the Fischer committee was even rumored to be addressing the issue of leveraged stock buybacks. It would generate a violent sell-off of the likes not seen since the House Republicans voted down TARP the first time around.

And then would come the information miasma. Wall Street would trot out the cash on the sidelines canard, arguing there is no problem here because notwithstanding the current $700 billion annualized run-rate of buybacks for the S&P 500 alone, there is plenty of cash cushion available to corporate chieftains who wish to invest in their own company’s future— albeit with shareholder money, not theirs.

In truth, of course, the business sector did not delever one wit after the financial crisis. Since the fourth quarter of 2007, business debt in the US has risen from $11 to $14 trillion. That $3 trillion gain dwarfs the $500 billion pick up in business cash balances. In fact, the rise in cash was never a sign of returning financial health in the fist place: it was only a telltale signal that by causing debt to be drastically mis-priced, the Fed was encouraging companies to artificially balloon both sides of their balance sheets.

It's amazing that the world snapped right back to the way it was.

Nagh. This is the new normal and we are yet to discover all that is prepared for us in it

- Free trading apps

- Over 8,000 signals for copying

- Economic news for exploring financial markets

You agree to website policy and terms of use

Probably most people would agree that the people paid by the U.S. government to regulate Wall Street have had their difficulties. Most people would probably also agree on two reasons those difficulties seem only to be growing: an ever-more complex financial system that regulators must have explained to them by the financiers who create it, and the ever-more common practice among regulators of leaving their government jobs for much higher paying jobs at the very banks they were once meant to regulate. Wall Street's regulators are people who are paid by Wall Street to accept Wall Street's explanations of itself, and who have little ability to defend themselves from those explanations.

Our financial regulatory system is obviously dysfunctional. But because the subject is so tedious, and the details so complicated, the public doesn't pay it much attention.

That may very well change today, for today -- Friday, Sept. 26 --- the radio program "This American Life" will air a jaw-dropping story about Wall Street regulation, and the public will have no trouble at all understanding it.

The reporter, Jake Bernstein, has obtained 46 hours of tape recordings, made secretly by a Federal Reserve employee, of conversations within the Fed, and between the Fed and Goldman Sachs. The Ray Rice video for the financial sector has arrived.

First, a bit of background -- which you might get equally well from today's broadcast. After the 2008 financial crisis, the New York Fed, now the chief U.S. bank regulator, commissioned a study of itself. This study, which the Fed also intended to keep to itself, set out to understand why the Fed hadn't spotted the insane and destructive behavior inside the big banks, and stopped it before it got out of control. The "discussion draft" of the Fed's internal study, led by a Columbia Business School professor and former banker named David Beim, was sent to the Fed on Aug. 18, 2009.

It's an extraordinary document. There is not space here to do it justice, but the gist is this: The Fed failed to regulate the banks because it did not encourage its employees to ask questions, to speak their minds or to point out problems.

Just the opposite: The Fed encourages its employees to keep their heads down, to obey their managers and to appease the banks. That is, bank regulators failed to do their jobs properly not because they lacked the tools but because they were discouraged from using them.

The report quotes Fed employees saying things like, "until I know what my boss thinks I don't want to tell you," and "no one feels individually accountable for financial crisis mistakes because management is through consensus." Beim was himself surprised that what he thought was going to be an investigation of financial failure was actually a story of cultural failure.

Any Fed manager who read the Beim report, and who wanted to fix his institution, or merely cover his ass, would instantly have set out to hire strong-willed, independent-minded people who were willing to speak their minds, and set them loose on our financial sector. The Fed does not appear to have done this, at least not intentionally. But in late 2011, as those managers staffed up to take on the greater bank regulatory role given to them by the Dodd-Frank legislation, they hired a bunch of new people and one of them was a strong-willed, independent-minded woman named Carmen Segarra.

I've never met Segarra, but she comes across on the broadcast as a likable combination of good-humored and principled. "This American Life" also interviewed people who had worked with her, before she arrived at the Fed, who describe her as smart and occasionally blunt, but never unprofessional. She is obviously bright and inquisitive: speaks four languages, holds degrees from Harvard, Cornell and Columbia. She is also obviously knowledgeable: Before going to work at the Fed, she worked directly, and successfully, for the legal and compliance departments of big banks. She went to work for the Fed after the financial crisis, she says, only because she thought she had the ability to help the Fed to fix the system.

In early 2012, Segarra was assigned to regulate Goldman Sachs, and so was installed inside Goldman. (The people who regulate banks for the Fed are physically stationed inside the banks.)

The job right from the start seems to have been different from what she had imagined: In meetings, Fed employees would defer to the Goldman people; if one of the Goldman people said something revealing or even alarming, the other Fed employees in the meeting would either ignore or downplay it. For instance, in one meeting a Goldman employee expressed the view that "once clients are wealthy enough certain consumer laws don't apply to them." After that meeting, Segarra turned to a fellow Fed regulator and said how surprised she was by that statement -- to which the regulator replied, "You didn't hear that."

This sort of thing occurred often enough -- Fed regulators denying what had been said in meetings, Fed managers asking her to alter minutes of meetings after the fact -- that Segarra decided she needed to record what actually had been said. So she went to the Spy Store and bought a tiny tape recorder, then began to record her meetings at Goldman Sachs, until she was fired.

(How Segarra got herself fired by the Fed is interesting. In 2012, Goldman was rebuked by a Delaware judge for its behavior during a corporate acquisition. Goldman had advised one energy company, El Paso Corp., as it sold itself to another energy company, Kinder Morgan, in which Goldman actually owned a $4 billion stake, and a Goldman banker had a big personal investment. The incident forced the Fed to ask Goldman to see its conflict of interest policy. It turned out that Goldman had no conflict of interest policy -- but when Segarra insisted on saying as much in her report, her bosses tried to get her to change her report. Under pressure, she finally agreed to change the language in her report, but she couldn't resist telling her boss that she wouldn't be changing her mind. Shortly after that encounter, she was fired.)

I don't want to spoil the revelations of "This American Life": It's far better to hear the actual sounds on the radio, as so much of the meaning of the piece is in the tones of the voices -- and, especially, in the breathtaking wussiness of the people at the Fed charged with regulating Goldman Sachs. But once you have listened to it -- as when you were faced with the newly unignorable truth of what actually happened to that NFL running back's fiancee in that elevator -- consider the following:

1. You sort of knew that the regulators were more or less controlled by the banks. Now you know.

2. The only reason you know is that one woman, Carmen Segarra, has been brave enough to fight the system. She has paid a great price to inform us all of the obvious. She has lost her job, undermined her career, and will no doubt also endure a lifetime of lawsuits and slander.

So what are you going to do about it? At this moment the Fed is probably telling itself that, like the financial crisis, this, too, will blow over. It shouldn't.

source