Was Tom Hayes Running the Biggest Financial Conspiracy ever?

Especially, Hayes was taking positions in interest rate swaps. Initially intended to shield organizations from changes in premium rates, swaps were currently for the most part purchased and sold between proficient dealers at banks and multifaceted investments, another type of high-stakes security to wager on. The business sector for swaps was blasting. In 2000, $50 trillion of the securities changed hands consistently. In 2010, it was $500 trillion. For Hayes, the intricate counts and consistent mental effort came effectively, yet he discovered he had something rarer: a steely stomach for danger. While other newbie merchants hoped to book picks up or control misfortunes rapidly, Hayes rode out unpredictable business sector swings. In those early years his outcomes were blended, however his bosses knew a whiz when they saw one. In 2004, Hayes was headhunted by Royal Bank of Canada, a littler outfit where Hayes could take a more noticeable part. He was given his own particular exchanging book concentrated obsessed.

Hayes cherished his occupation, however when things weren't going his direction, he loathed it generally as wildly. On the fifth floor of UBS's Tokyo home office, he gazed at his bank of screens, raging. It was October 2006. He'd been at the bank just a matter of weeks and was at that point in a gap, on the losing side of a gigantic wager on the bearing of transient premium rates. Yen Libor was declining to move, and he was getting angrier.

While account had been changed by innovation over the past quarter-century, the way Libor was set stayed simple. Consistently, banks in London told the British Bankers' Association the amount it may cost them to acquire in different monetary forms, for different time spans. There were 150 aggregate mixes. For every one, the top and base quarter of figures are disposed of, and the staying's normal numbers turned into that day's Libor. That was it. Libor was a part in securities extending from U.S. understudy advances and charge cards to Kazakh gas prospects, yet it was resolved every day by only a modest bunch of diverted, guesstimating people.

Later that evening in Tokyo, Hayes was venting about his issue to one of his London handles, a trusted associate. The agent offered to converse with his associate, who was accountable for messaging a day by day Libor forecast—informal however helpful—to the little gathering of financiers that surfaced with the number. (The U.K. court has requested that the two men can't be named in light of the fact that they are confronting trial.) The email should be fair-minded, yet in the event that Hayes needed, the agent said, he could skew the direction lower. Possibly a portion of the lazier rate setters, the individuals who didn't do much business in the money at any rate, would essentially take after along.

For Hayes, it was a light minute. He realized that banks had constantly customized their Libor entries to advantage their own particular positions, yet the framework opposed altering: No single establishment could have much effect on the general rate when 15 different banks were doing likewise. In any case, Hayes had worked at enough banks and become a close acquaintence with such a large number of facilitates that he understood he could influence a few submitters on the double. He could pull their strings without them notwithstanding knowing it. What's more, Hayes was on preferred terms with his agents over most. They had in Hayes a related soul—a state school Londoner with a cockney accent.

Hayes' agent did as he was inquired. The intercession didn't have much effect, yet the thought had flourished. Soon thereafter Hayes did a reversal to the representative furthermore drew closer a second for good measure. This time, Hayes needed six-month yen Libor to go up. He had a 400 billion yen ($3.3 billion) position going to develop, and each increment of a hundredth of a rate point (or premise point) was worth a huge number of dollars. Hayes assaulted his merchants with IMs and telephone calls, and throughout the following couple of days the rate ascended by just about three premise focuses. Hayes messaged his manager, Mike Pieri, to express his joy that the arrangement had worked—imperceptibly, yet when reproduced by the span of Hayes' wagers, significantly. Soon thereafter, he kept in touch with his handle: "Whatever it takes, charge me."

Hayes found that Libor was anything but difficult to control, as well as shabby too. The London dealer had won his partner's collaboration by dangling simply a free curry. Hayes started connecting with dealers he knew at different banks, requesting their assistance in moving the rate. By the spring of 2007, his system had developed to incorporate brokers at RBS and JPMorgan Chase. One of his enlisted people was his stepbrother, Peter O'Leary, a graduate learner at HSBC in London.

After some babble over email in April, Hayes asked: "Do you know the fellow who sets yen Libors at your place? I think he exchanges yen and scandi money and his name is Chris Darcy."

"Ha better believe it I do!" O'Leary wrote. "His name is really Chris Porter I think. Everybody calls him Darcy, I think, cos he sounds really elegant."

Hayes approached O'Leary to squeeze his partner for low three-month Libor. Each premise point, he said, was worth $1 million. In a progression of telephone calls, Hayes advised his stepbrother how to make the methodology, recommending he get to know the man over a couple of pints. O'Leary was hesitant, taking note of that the rate setter chipped away at an alternate floor, in an alternate piece of the business. Hayes continued, and O'Leary in the long run hit his partner up for the support. Tommy Chocolate had progress significantly. Hayes later apologized to O'Leary for including him, and never requested a Libor support again.

At UBS he demonstrated no restraints. At normal 8:30 a.m. gatherings, he talked about his positions and disclosed to associates and managers how he wanted to impact the rate. That late spring, Hayes formalized his plan with one of his interdealer representatives. On top of the altered month to month charge UBS paid for its administrations, Hayes arranged an extra £15,000 a month for serving to move the benchmark, £5,000 of which was actually reserved for the merchant who sent the every day Libor expectation email.

A UBS representative said:"To propose that Hayes had a 'light' minute at UBS about Libor control is over the top. Neither Hayes nor UBS concocted or started LIBOR control. It was extensive behavior including numerous banks and merchants acting exclusively and by and large over a drawn out duration of time."

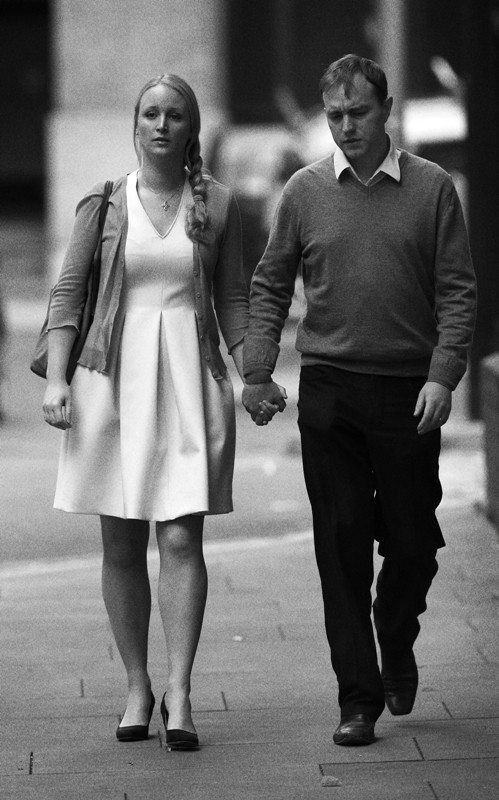

Hayes never knew for certain the amount of impact he had. In any case, on the off chance that he couldn't exactly control the future, he could give it a push in whatever bearing he needed. Hayes later assessed that his capacity to move the rate represented maybe 10 percent of his benefits—however in a ferocious business, it was an edge over his rivals that helped imprint him as a star at UBS and make $50 million for the bank in 2007. That September, at a Tokyo swimming pool, he met a corporate attorney named Sarah Tighe, a kindred Brit a long way from home. Later, Tighe listened to Hayes drift about the fortune he made off the breakdown of Northern Rock bank—and still needed to see him once more. This was a manager, somebody who discovered his characteristics charming and his aspiration appealing. Out of the bedlam of businesses and regular life, Tom Hayes was making request.

This record is taking into account more than 200 meetings with dealers, intermediaries, controllers, legal counselors, and administrators, and also a large number of archives and messages presented at his inevitable trial.

On an unseasonably chilly April morning in 2008, Vince McGonagle shut the entryway of his office at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in Washington and settled into read the morning papers. Little and wiry, with a hangdog expression, McGonagle had been at the authorization division of the CFTC for a long time, amid which time his red hair had turned dark around the edges. He was presently a senior director. The feature on Page 1 of the Wall Street Journal read, "Investors Cast Doubt on Key Rate Amid Crisis."

It started: "A standout amongst the most vital gauges of the world's budgetary wellbeing could be sending false flags. In an improvement that has suggestions for borrowers all over, from Russian oil makers to property holders in Detroit, brokers and dealers are communicating worries that the London interbank offered rate, known as Libor, is getting to be inconsistent."

The story recommended that banks were giving intentionally low gauges of their getting expenses to abstain from "tipping off the business that they're frantic for money." Before the monetary area had started to hint at disastrous shortcoming in mid 2007, few individuals in McGonagle's reality thought about Libor. The benchmark was a critical however unsurprising piece of the money related pipes that scarcely moved from week to week or bank to bank. Presently it had turned into a firmly took after pointer of anxiety in the business sectors.

As credit solidified, Libor in all monetary forms shot up. Saves money with the most noteworthy entries were singled out as battling. A day by day amusement created in which Libor-setters, prodded on by senior administrators, attempted to foresee what their opponents would submit, and afterward come in marginally lower. With so small exchanging the money market, it was difficult to check the veracity of their entries. A few investigators evaluated that the distributed rates were as much as 40 premise focuses beneath where they ought to be. The inspiration for lowballing had nothing to do with benefit: This spoke the truth survival. National financiers and speculators were chasing for any indication of who may take after Bear Stearns into the pit of liquidation.

The rate setters had no clue what to present every morning, and turned out to be much more subject to their specialists—dealers who were in Hayes' pocket.

McGonagle knew minimal about Libor, however the Journal story made him suspicious. Not long after joining the office in 1996, he'd been one of a group of attorneys delegated to research Dynegy, a Texas vitality organization, over affirmations it had lied about the amount of regular gas it was purchasing and offering with a specific end goal to impact the ware's benchmarks. The CFTC and different organizations at last fined Dynegy and more than two dozen different organizations, including Enron, more than $300 million.

There was no notion in the spring of 2008 that dealers were pushing Libor around to help their own particular benefits, yet to McGonagle, the similitudes were striking: Here was a benchmark that depended on the trustworthiness of merchants who had an immediate enthusiasm for where it was set. While common gas benchmarks were assembled by privately owned businesses, Libor was supervised by the BBA, a London-based campaigning gathering with a notoriety for being an industry team promoter. In both cases, the body in charge of administering the rate had no correctional forces, so there was little to demoralize firms from conning.

A honing Catholic, McGonagle got his law degree from Pepperdine University, a Christian school in California where he considered more important than most the mission of an existence of "reason, administration, and initiative." While schoolmates took generously compensated positions guarding organizar.

Hayes couldn't have picked a more awful individual to annoy. Citi was at that point participating with the CFTC's examination concerning Libor gear, and Thursfield had even conveyed a 18-page presentation by means of feature connection to agents in March 2009 on the rate-setting procedure. Hayes, as far as concerns him, thought minimal about the meeting and later couldn't much recollect Thursfield's name.

At the point when Hayes at long last appeared to Citi's workplaces at Tokyo's Shin-Marunouchi Building in December, his arrangements unwound. Not just did the bank's submitters let him know more than once they couldn't consider his positions when setting Libor, even his old partners began betraying him. Word had spilled out about the CFTC's examination, and individuals were getting anxious. "I asked him a short time prior and he f - said to me not to ask him again but rather I will attempt, mate," one intermediary told Hayes, who had been harassing him. "They've all got right f - clever on it as of late."

Hayes additionally began making appallingly terrible approaches the business and was racking up huge misfortunes. In June, after a Citi associate quit and spilled subtle elements of Hayes' exchanging book to his old supervisor at UBS, they collaborated with others in the business sector to focus on his powerless spots. Pushing the business against him, they cost the dealer about $100 million.

At the last part of one of the most exceedingly bad months of his profession, Hayes was getting urgent. Sitting at his work area on June 25, with his benefit and misfortune record looking more regrettable than any time in recent memory, Hayes grabbed his cell telephone and dialed Hoshino's versatile in London. Despite the fact that he'd been told over and over that the rate setters weren't upbeat discussing Libor, Hayes requested his subordinate to approach them once more. He had a gigantic exchange developing toward the month's end and required the benchmark up.

In Hoshino, Hayes had picked a poor associate. Modest and known as "Little Hoshino" around the workplace, Hoshino had never really drawn nearer the submitters when Hayes had inquired. With his wavering English, the youthful broker discovered them excessively threatening. This time, Hayes was more unyielding than common. Soon after lunch, Hoshino made the short stroll over the exchanging floor to the rate setter's work area and went on Hayes' solicitation. It was a lethal stumble. The CFTC had quite recently subpoenaed Citi and requested it to test whether their subordinates brokers were attempting to fix the rate. Mindful of the warmth on the bank, the submitter told Hoshino he was being wrong and reported the way to deal with Thursfield, who quickly called the bank's consistence office.

In the months that took after, Hayes was met for over 12 hours by Citi's attorneys. His managers told Hayes he would be fine, that it was a piece of a more extensive examination. At that point, on Sept. 6, as Hayes advanced into the workplace, he was maneuvered into an unremarkable meeting room. He saw the two Citi administrators who'd employed him not as much as a year prior, Andrew Morton and Brian McCappin, sitting at a gathering table, looking grave. Citigroup's general guidance and head of HR in Japan were additionally there. (Morton, McCappin, Thursfield, and Hoshino did not react to asks for input sent through Citigroup.)

As Hayes sat, McCappin said the bank had been exploring him for quite a long time and had revealed different scenes of his controlling rates. Such direct damaged the bank's implicit rules, and he was being let go. Hayes was stunned. Just the earlier week, he'd been exchanging as common and talking about techniques with McCappin in his corner office.

Distinctively, Hayes recuperated rapidly from the stun. "All things considered, that is kind of unexpected that you're terminating me, given that you were included in it up to your eyeballs," Hayes later reviewed telling McCappin.

"Goodness, yet he wasn't," the general guidance said rapidly. "He didn't have any exchanging positions."

Hayes questioned the point—as the leader of Citi's venture bank in Japan, McCappin had extreme obligation regarding each exchange—and afterward made an amazing counterattack. "The amount of are you going to pay me to go unobtrusively?" he inquired. "Else, I'm going to make a genuine object about this."

Citi hadn't been expecting that. The officials requested that Hayes leave the room while they talked about his agreement. Subsequent to getting back to him back in, they told Hayes that he wouldn't get any new cash. Be that as it may, he could keep his $3 million marking reward.

In the months that took after, Hayes did his best to remake his life. Days after his release, he came back to England and wedded Tighe in a rich function at the Four Seasons inn in rustic Hampshire. In 2011, they had their first kid, Joshua, and purchased the Old Rectory, a six-room previous vicarage in a lovely town outside London. They paid the £1.2 million ($1.9 million) cost in real money, with no home loan, as per area records. Hayes needed a British MBA course, and Tighe kept up her role as a legal advisor. Together they started to rebuild their slope idyll, including another wing and documenting arrangements to manufacture a six-foot electronic door to keep out gatecrashers.

In the interim, U.S. examiners were crushing ahead with their case. Hayes heard bits of gossip however had no chance to get of knowing he was one of the prime targets. He sent a Facebook message to Mirhat Alykulov, a broker who'd sat beside him for quite a long time at UBS Tokyo, and one day a few weeks after the fact, he recovered a call. Hayes remove any talk and asked: Had the bank said anything in regards to identifying with the Justice Department? Unbeknownst to Hayes, Alykulov was calling from his criminal legal advisor's office in Washington on a recorded line the FBI had set up to show up as though it began in Tokyo. As calmly as he could oversee, Alykulov asked Hayes what he wanted to do. Alykulov, who was confronting Libor misrepresentation charges he could call his own, had given a break with the feds—they concurred not to indict in the event that he let them know all that he knew and helped pin Hayes. On the off chance that Hayes proposed they mislead the administration, he could be accused of obstacle and in addition extortion.

Hayes delayed, as though by one means or another mindful of the trap. "The U.S. Bureau of Justice, mate, you know, they're similar to the fellows who, you know, you know, completely like, you know, you know—place individuals in prison," Hayes said. "Why the damnation would you need to converse with them?" (Alykulov, through his attorney, declined to remark.)

Two weeks prior Christmas in 2012, at 7 a.m. on a Tuesday, Hayes heard a thump at the entryway. More than twelve cops and Serious Fraud Office examiners cleared through the property, gathering PCs and archives into boxes. Hayes was captured, taken to a London police headquarters, and advised he was associated with scheme to cheat.

Hayes declined to remark and was discharged. After eight days, he would later affirm, Hayes was staring at the TV when a release slice to a question and answer session in Washington. Before blazing cameras, U.S. Lawyer General Eric Holder declared that UBS had been fined $1.5 billion and had conceded to fixing Libor at its Japanese arm. The DOJ was likewise criminally charging Hayes and a previous associate, Roger Darin, and trying to remove them. Hayes had no idea.

Hayes considered the proof against him. Agents on three mainlands had a great many his implicating messages and sound recordings. The best way to dodge removal to the U.S. also, its unforgiving sentencing laws, Hayes' legal advisors let him know, was to enter a "supergrass" (witness) bargain in the U.K., admitting everything and surrendering everybody he'd teamed up with. The British were willing to give a break. They'd been late to the examination yet at the same time needed a blameworthy request at home.

So started a time of exceptional unburdening. Throughout the following three months, Hayes' life steered into a recognizable schedule. At any rate once per week, he would advance toward the SFO, simply off Trafalgar Square. In the wake of marking in less than a false name—typically some previous legend from his darling Queens Park Rangers soccer group—he took the lift to the fourth floor, strolled past the candy machines, and ventured into his confession booth: a stark white room with a work area, a projector, his legal advisor, and two examiners in suits. They scarcely needed to push to inspire him to talk.

"The main thing you think," Hayes said from the get-go, "is the place's the edge, where would I be able to profit, by what means would I be able to push, push the limits, possibly, you know, somewhat of a hazy area, push the envelope's edge." He at last delayed for breath. "Be that as it may, the fact of the matter is, you are covetous, you need each and every bit of cash that you can get in light of the fact that, similar to I say, that is the way you are judged, that is your execution metric."

The shorter, stockier agent started: "At the time that the behavior occurred, do you think you knew by then, that what you … ."

"Well look, I mean it's an unscrupulous plan, isn't it?" Hayes intruded. "What's more, I was a piece of the untrustworthy plan, so clearly I was being unscrupulous." Hunched over a work area in the confined investigation room, he gazed blankly ahead as he dispatched into another cathartic downpour.

Hayes appeared to relish remembering minutes from his past, his voice accelerating when he portrayed powerful days heaping into positions, crushing the best costs from representatives, and playing merchants against one another. "Exchanging a huge subsidiaries book," he said amid one trade, "is similar to caring for a major, living life form. In the wake of exchanging for a considerable length of time and years you get a characteristic feeling for how everything relates."

In June, following 82 hours of meetings, Hayes was formally charged. He had distinguished more than 20 individuals as co-schemers, including his own stepbrother. (O'Leary is not confronting charges, nor Pieri, Hoshino, and McCappin.) The rundown included dealers at JPMorgan, RBS, Deutsche Bank, and HSBC, and additionally specialists at the two greatest interdealer business firms. For Hayes, deceiving the men was levelheaded. Realizing that he would serve a poss

https://www.mql5.com/en/signals/111434#!tab=history